[Summer 2010]

Seeing «the Frame that Blinds us»1

par Amish Morrell

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag describes Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya’s series of eighty-three etchings, The Disasters of War, made between 1810 and 1820, as offering the first comprehensive and graphic portrayal of war. Consisting of scenes of executions, physical combat, soldiers’ assaults upon civilians, injury, and starvation, the prints present a disturbing and shocking account of the 1808–14 war among Spain, France, Britain, and Portugal. Sontag wrote that with this work “a new standard of responsiveness for suffering enter[ed] art.”2 She notes that the images, captioned with titles that highlight the horrors of war, are intended to elicit a moral response. Their subject matter makes their meaning seem incontrovertible, and they are part of what has since become a long practice of using images of war to achieve particular ends: to evoke horror, to command action, and to elicit support. In War at a Distance, Blake Fitzpatrick, Karyn Sandlos, and Roger Simon purposely avoid showing such graphic subject matter. Juxtaposing works made by journalists, artists, illustrators, and soldiers, they instead provoke another kind of thought, turning their contemplation away from their subject matter to the devices of their framing.

(…) some experiences are simply unrepresentable: trauma, suffering, and death. This is a problem central to photography itself, in that it makes it seem that the unknowable can be known.

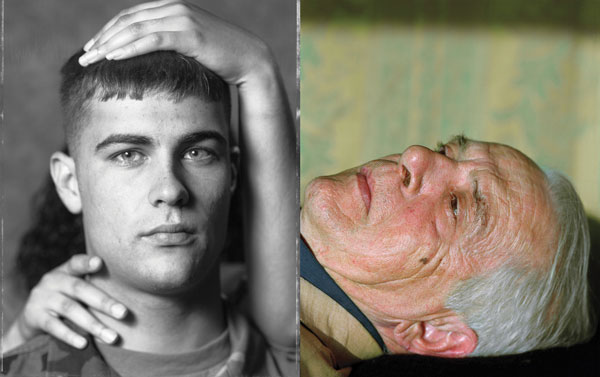

In Suzanne Opton’s photographs from her Citizen +Soldier series, Iraqi citizens and American soldiers are shown absorbed in thought, avoiding the photographer’s gaze. Enlarged so that they accentuate details such as the pores and creases in the subjects’ skin and the texture and body of their hair, Opton’s photographs create a sense of physical proximity and intimacy. Without further context – the images are cropped to avoid signifiers of identity and suggestions of their surroundings – they appear politically neutral, and yet affecting. They take on other meaning, however, when placed next to the subjects’ testimonial accounts of the war in Iraq. This pairing sheds valuable insight into the image’s ability to provide access to another person’s experience of these events. The photographs index an experience of the war that they are also incapable of revealing. Juxtaposed with the subjects’ testimonies, they reveal the very structures of mediation through which war is encountered.

The critique of representation in shaping viewers’ understanding of war has fallen into several broad categories, in all of which the image enacts a particular kind of relationship between the viewer and the photographed subject. First, images have often been part of the very apparatus of war itself. Harun Farocki’s 2003 film, also titled War at a Distance, describes the role of imaging technologies in enabling war to be fought remotely, such as video cameras installed in cruise missiles so that they can be accurately guided to their targets. This is not dissimilar from the infamous situation at the Abu Ghraib prison, where guards made and circulated photographs of prisoners being forced to perform sexual acts and threatened to send them to the prisoners’ families as a way of further extending their humiliation. Here, the production and circulation of images functioned as a mechanism of state torture. A second critique is that some experiences are simply unrepresentable: trauma, suffering, and death. This is a problem central to photography itself, in that it makes it seem that the unknowable can be known. The effect is that the repetition of images of disaster and suffering dulls viewers’ capacity for empathic identification and elevates their ability to behold atrocity. While seeming to bring the war closer, these representations instead distance the viewer from the events that they depict.

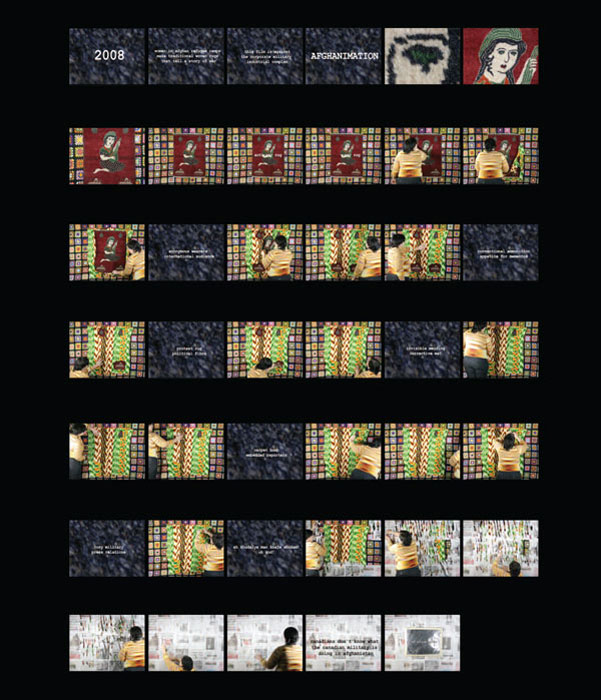

Among the images chosen for War at a Distance, there are no photographs of the dead. Few of the works depict war using traditional documentary media or techniques. The best of example of this is Allyson Mitchell’s video work Afghanimation, in which she overlays domestic textiles, including macramé blankets, with Afghan war rugs and newspapers covering the war, in a montage that also includes expressions such as “carpet bombing.” In describing the war, Mitchell’s work also references a domestic realm. While Afghanimation draws attention to language and its simultaneous purchase within the military and household spheres, Graeme Smith’s Talking to the Taliban incorporates a voice that is rarely heard and that provides a perspective from both inside and outside of conventional journalistic coverage. As part of a project for the Globe and Mail, interviewers asked members of the Taliban a series of twenty questions, ranging from “How long will you fight against non-Muslims ?” to “Do you know Bush ?” and “Who is Stephen Harper ?” The responses to Smith’s questions are unusual, and often unexpected. Both the questions and the answers offer important reflections on the role of propaganda – on how language and ideology structure how we know these events – but they also offer a space to reflect on what is not known and, in some, on what is not seen.

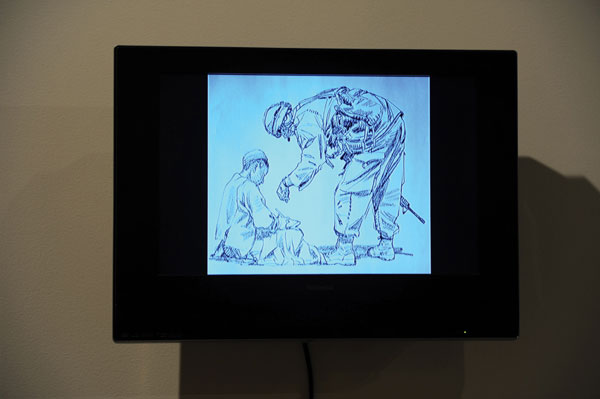

The works that describe war in the most conventional manner include Louie Palu’s photojournalistic images depicting everyday events in the lives of soldiers stationed in Afghanistan, which have been paired with audio recordings of sounds from the battlefield, and Richard Johnson’s drawings, Postings from Afghanistan, which were published in The National Post. The audio track that accompanies Palu’s images has the effect of extending the viewer’s engagement with the images, creating a space for an encounter with their subjects that is not simply visual and momentary, but aural and reflective. Johnson’s sketches, which include journal notes and observations, facilitate a similarly reflective engagement. His drawings resemble some of the earliest war photographs – those made by the British photographer Roger Fenton in 1855 during the Crimean war – in that they show what is peripheral to events of battle: soldiers standing around, portraits of officers, military machinery, and buildings. Like Fenton’s photographs, with their long exposure times dictated by early photographic technology, Johnson’s drawings function, the curators note, to “slow time down.” But they also “reveal pauses in the conduct of war – moments of encounter shared between Canadian soldiers, and with the Afghani environment and citizens.”3 attention. A similar examination is enacted by the inclusion of a second sound installation that played episodes of the radio play Afghanada, which aired on the CBC in 2006 and 2007.4 Dramatizing the lives of several Canadian soldiers stationed in Afghanistan, it presents a fictional counterpoint to the journalistic authority of Palu’s images. Here, the Canadian characters speak with various regional accents, and their stories become a palimpsest of Canada and Afghanistan, conjuring a space in which the listener imagines and identifies with the characters. Its inclusion foregrounds how fiction operates as a framing device.

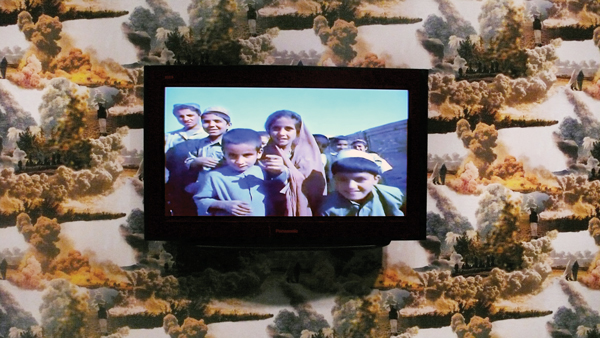

The inclusion of multiple kinds of media is crucial to the questions explored within this project. Several video monitors show YouTube videos made by soldiers recorded with helmet-mounted cameras. Jerky low-resolution images show soldiers running down a road in the rain and sleet, shots being fired, and a herd of sheep scattering. Paralleling Farocki’s images of camera-guided cruise missiles directed by soldiers sitting at a control station, here the soldiers carry the cameras, and YouTube viewers follow them as they encounter their enemies. Videos such as these, distributed in this manner, have a mass potential audience, and the footage can be replayed again and again. This repetition is mirrored in the background of Francesco Simeti’s Watching the War, an installation that consists of wallpaper made up of images of bomb blasts from the war in Iraq. In Simeti’s installation, war becomes pretty and banal, devoid of its impact.

The aestheticization of war is further and, perhaps, more explicitly addressed in Stephen Andrews’s The Quick and the Dead. Andrews made a series of images by rubbing cyan, magenta, yellow, and black crayons on parchment paper, re-creating video footage of the bombing of an American convoy in Iraq. These are exhibited both as a series of prints and as a video animation. The response that these images elicit is not horror, but a sense of beauty. Through the repetitive process of making crayon rubbings, Andrews reduces the image to its most formal elements and then reconstructs it with realistic effect. While these works raise questions about how the mass media shape people’s collective understanding of disaster, what is unsettling about them is their very aestheticism – one cannot help but find them beautiful – and how this so disturbingly juxtaposes the horror that they describe. In Frames of War, Judith Butler writes, “The indefinite circulability of the image allows the event to continue to happen.”5 For Butler, the event keeps repeating itself through the photograph. The beautiful repetition of Andrews’s images stages a betrayal of the senses, a betrayal that, in turn, is exposed by the animation.

While the event may keep repeating, as it does for the subjects of Opton’s images, who are caught in acts of remembering the Iraq war, it remains corporeally inaccessible to those who encounter it only through photographs. One of the curatorial intentions of this project was to help us think about how we understand war from a distance, as we do through audio and visual texts. But it is neither the war nor death that we seek to understand. Rather, it is how things become known, how they are described and framed, and how they are complicit in what they depict. Butler observes, “To learn to see the frame that blinds us to what we see is no easy matter.”6 Through its juxtaposition of works, this project attempts to help us understand how we understand that which we cannot see.

1 Judith Butler, The Frames of War (London: Verso, 2009), p. 100. War at a Distance, presented by Gallery TPW, included works by Stephen Andrews, Richard Johnson, Allyson Mitchell, Suzanne Opton, Louie Palu, Francesco Simeti, and Graeme Smith.

2 Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), p. 45.

3 Blake Fitzpatrick, Karyn Sandlos, and Roger I. Simon, curators’ essay, War at a Distance: Visual Culture and the Framing of Public Conversations about Canadian Forces in Afghanistan (Toronto: Gallery TPW, 2009), p. 4.

4 For more information on this project, go to : http://www.cbc.ca/afghanada/

5 Butler, Frames of War, p. 86.

6 Ibid., p. 100.

Curators Blake Fitzpatrick (who is also a photographer), Karyn Sandlos, and Roger I. Simon are professors specializing in the media, photography, and education, affiliated, respectively, with Ryerson University (Toronto), the School of the Art Institute (Chicago), and the University of Toronto. A symposium on “documentary practices, visual culture, and the public debate on military conflicts” was also presented at Ryerson University to complement the exhibition.

Amish Morrell is the editor of C Magazine, a quarterly publication on contemporary international art. He has a Ph.D. in cultural studies and education from the Univer- sity of Toronto and has written for publications including Art Book, Canadian Art, Ciel variable, and Prefix Photo. He teaches visual culture, the history of photography, art and activism, and cultural memory studies at the University of Toronto and the Ontario College of Art and Design.