[Winter 2013]

by Karen Henry

Who would have thought that the 1980s were such a stimulating time. There is so much emphasis in cultural memory on the 1960s and 1970s that it seemed like it was all over by the 1980s – but not so, as revealed in the two-part exhibition on photography in Vancouver c. 19831. The 1980s are found to have been a lively transitional moment between the social upheaval and conceptual austerity of earlier decades – when photography was the sidekick, supporting and documenting life, politics, performance, and the idea, without artifice – and the more aesthetic, historicized, and market-driven forms that came to be more dominant afterward. The exhibition portrays a highly productive time when the medium of photography was becoming relevant in its own right, pushing out of the frame and into physical space, and when light and photo emulsion were becoming material. At the same time, the works in this exhibition are not limited by this technical self-reflection. They are experimental in form but also engaged in social concerns and considerations of the role of photography in memory, mass culture, and illusion. The exhibition offers a rich array of presentation devices largely informed by the idea of montage – photo collages, composite and sequential images, and fragmented narratives. It includes gritty black-and-white photographs, exquisite colour abstractions, photo emulsions on canvas, a book project, slide works, film, video, and newsprint, as well as variations in scale, from a small newsprint cut-out on a large wall (Ken Lum’s World Portraits, 1983) to the large, vertical, figurative photo mural by Ian Wallace (The Imperial City, 1986).

Who would have thought that the 1980s were such a stimulating time. There is so much emphasis in cultural memory on the 1960s and 1970s that it seemed like it was all over by the 1980s – but not so, as revealed in the two-part exhibition on photography in Vancouver c. 19831. The 1980s are found to have been a lively transitional moment between the social upheaval and conceptual austerity of earlier decades – when photography was the sidekick, supporting and documenting life, politics, performance, and the idea, without artifice – and the more aesthetic, historicized, and market-driven forms that came to be more dominant afterward. The exhibition portrays a highly productive time when the medium of photography was becoming relevant in its own right, pushing out of the frame and into physical space, and when light and photo emulsion were becoming material. At the same time, the works in this exhibition are not limited by this technical self-reflection. They are experimental in form but also engaged in social concerns and considerations of the role of photography in memory, mass culture, and illusion.

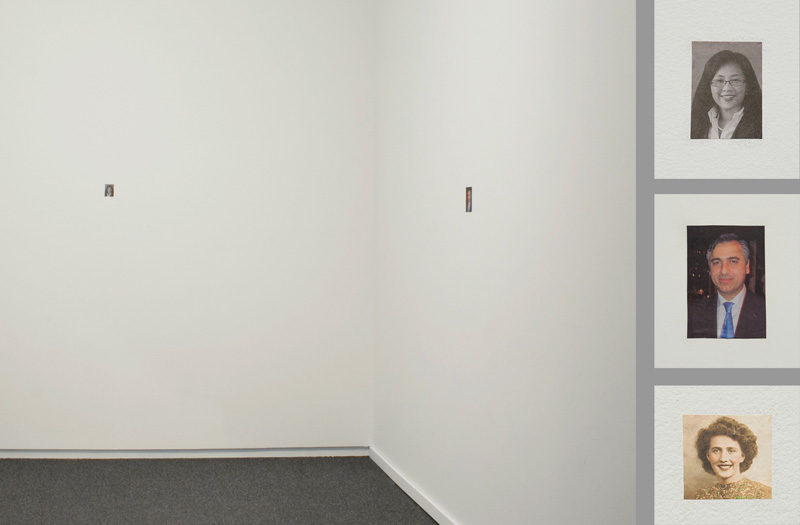

The exhibition offers a rich array of presentation devices largely informed by the idea of montage – photo collages, composite and sequential images, and fragmented narratives. It includes gritty black-and-white photographs, exquisite colour abstractions, photo emulsions on canvas, a book project, slide works, film, video, and newsprint, as well as variations in scale, from a small newsprint cut-out on a large wall (Ken Lum’s World Portraits, 1983) to the large, vertical, figurative photo mural by Ian Wallace (The Imperial City, 1986).

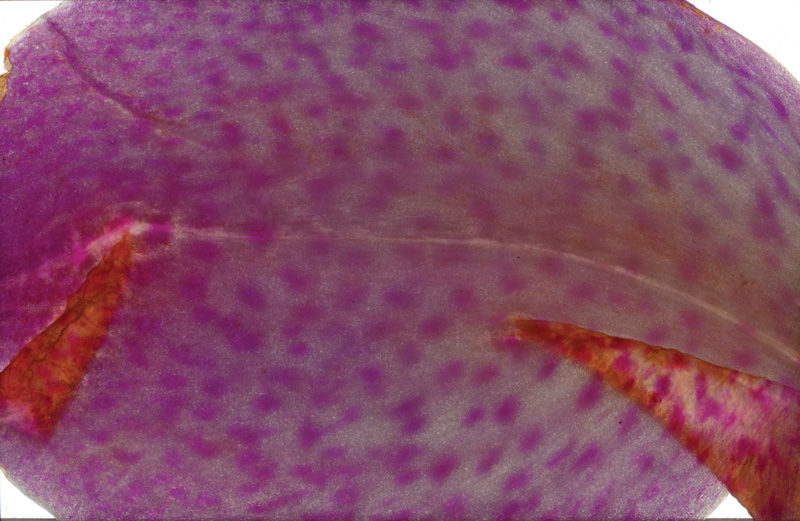

I left both parts of the exhibition feeling sentimental about the technologies of the past – Share Corsaut’s lush, unique, abstract photograms utilizing the unparalleled colour quality of the Polaroid process; photo montages and large black-and-white photographs produced by the artists in the darkroom; experimentation with the early version of video technology; densely coloured and lit slides and the mechanical sound of the projector – their demise foretold in Stan Douglas’s piece Residence (1982), which contemplates the fading of the image over time – and Laiwan’s even more fragile slide project using actual flower petals (She who scanned the flower of the world, 1987). The scale of works in the exhibition is restrained by the time frame, just prior to the availability of technologies to produce very large colour images.

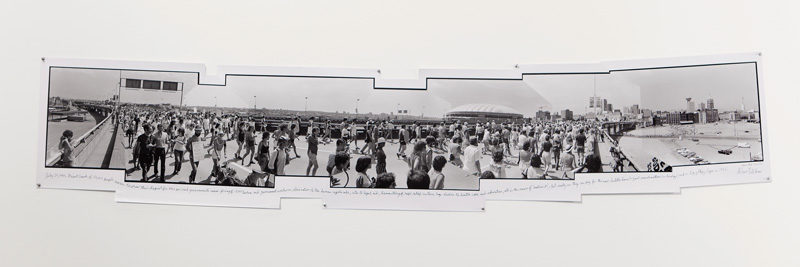

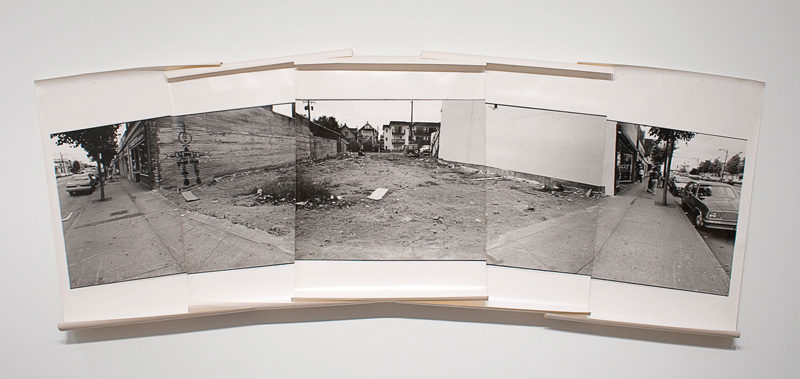

The exhibition incorporates film and video in separate screenings, including Rodney Graham’s Two Generators (1984), a night shot of a rushing river dominated by the sound of diesel generators used to power the lights, inviting reflection on resources and industry in British Columbia as well as romanticism, and Chris Gallagher’s film Terminal City (1982), which documents the destruction of a building to make way for development, echoed by one of Marian Penner Bancroft’s projects in the exhibition, Spiritland/Octopus Books, Fourth Avenue (1987), which marks the loss of an important local resource and the beginning of the development boom in Vancouver. The exhibition is situated in place as well as time. The changing face of Vancouver and surrounds is also documented in False Creek Panoramas (1984–85) by Chris Dikeakos and in Henri Robideau’s composite image July 23, 1983, Giant crowd of 50,000 people (1983) and Michelle Normoyle’s black-and-white five-piece mural British Properties (1987).

Light boxes assert a presence here through Kati Campbell’s works Possessed/Possession (1985) and Production (1984), monochrome associations of images relevant to the position and construction of women in domestic space. Ellie Epp also constructs a luminescent box of light and colour entitled Current (1984) that is reminiscent of the abstractions of South American kinetic artists. There are no light boxes by Jeff Wall, who is noticeably absent from this exhibition, though he remains a presence by association. His inclusion might have meant a loss of opportunity for showing some of the lesser-known works that are important to establishing the vitality of the period. Another missing artist who comes easily to mind is Roy Arden, who was working on the series Fragments in the early 1980s.

One of the pleasures of the show is the fluidity of mediums and associations – Ian Wallace’s partnering of colour-field painting on canvas, nineteenth-century romanticism, and photo imaging; the oblique pointillist associations in Liz Vanderzaag’s video Through the Holes; Corsaut’s structuralist colour/ground abstractions mentioned above; drawings and video animation in Metcalfe and Bull’s Sax Island (1984) video; and the sculptural presence of some of the works, including the long paper roll of Chris Dikeakos’s Column Ruin (1987).

In an accompanying discussion, Bill Wood, Ian Wallace, and Arnie Haraldsson spoke of the relationship with texts – literary inspirations and their own writing about each other, contextualizing and articulating post-conceptual practice, developing a critical framework of the time. Although the early 1980s was an important moment for establishing photography on the international stage, and in Vancouver most particularly the staged images in relation to modernism, I was struck by how much the works in this exhibition were informed by the critical strategies of feminism – collage and series of images – rather than a more direct representation and the use of a poetic and narrative framework to interiorize perception, as in Arni Haraldsson’s photo series April (1986) or the deconstruction of the meaning of images by appropriating and rephotographing media images as artefacts, as in Mark Lewis’s folded magazine images from Burning (1988) and Vikki Alexander’s montages of landscape and romantic images from the series Between Dreaming and Living (1985).

Though I have conflated them in this review, the show was divided into two groupings nominally focused around “experimental and conceptual approaches to image making” through associations of images (Part I) and “the social impact of camera images” and the “construction of pictures” working with mass media images (Part II). Rodney Graham’s Millennial Project for an Urban Plaza (1986) stands as unique in this realm of picture making, and perhaps as a bridge of sorts between the two groupings, as an apparatus for viewing, but, like most photographs of the time, defined by technical boundaries of the field of view and subject to chance. In addition to these two presentations on the early 1980s, there was a follow-up exhibition, called “Phantasmagoria,” about the contemporary generation of experimentation with photography. Unfortunately, I was not able to see this exhibition, but in the on-line documentation, it seems that most of the works fit neatly into a frame: scale and medium are more consistent, and although art references are present, politics are much less apparent (existing but more oblique) and the work is less grounded in a specific place.

Helga Pakasaar is an exceptional curator who brings an intelligent curiosity and a fresh look to past periods, as can be appreciated in this exhibition and in other shows that she has organized, such as In Transition: Postwar Photography in Vancouver (1986) and The Just Past of Photography in Vancouver (1997, featuring photographers from the 1960s). The year 1983 is an interesting choice. There was an economic recession in the early 1980s, and Vancouver was beginning to gear up for its first international event, Expo 86. It is the year that the Vancouver Art Gallery moved into its new home atthe courthouse and had its inaugural exhibition, Vancouver Art and Artists, a major reflection on the Vancouver art scene of that time. Vancouver photography was beginning to have a presence on the international art stage. Karen Love became director of and curator at Presentation House Gallery and began to establish a focus on international photography.

The early 1980s were a defining moment in photography, not only in Vancouver but elsewhere. In the 1981 exhibition Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curator Peter Galassi provided the rationales to legitimize photography as part of the pictorial continuum. The exhibition c.1983 provides another kind of legitimizing for a practice that is a vital confluence of multiple strategies of representation, conceptualism, feminism, literature, art history, and cultural theory, and that remains central locally as well as internationally.

Karen Henry is a curator, writer, editor, and, currently, public art planner in Vancouver.