[Winter 2013]

Ever since Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914) first took his metric photographs, in which he tried to produce accurate maps of crime scenes, legal photography has always been, in spite of itself, a “photography of interiors.” This involved considerable technical constraints (cramped quarters with no place to pull back, poor of insufficient lighting, and so on), as Rodolphe Reiss (1875–1929) often demonstrated. Today, these photographs seem to us to be not simply “crime scenes,” but also actual pictures of private, even intimate interiors belonging to the lower and middle classes of the early twentieth century. Intimate spaces and cloistered places also seem to drive Corinne May Botz’s photographic approach. For her project Haunted Houses, she gathered accounts from people who said that they had lived in a haunted place and took pictures of their “homes” in which nothing truly ghostly seems to have been photographed, except perhaps a ray of light, a detail, a section of wall, or a too-banal bedroom. The place itself, one might say, and the weight of the testimonial were enough to attest that the house was somehow inhabited from within by an invisible drama. These places are shared, inhabited, haunted by something that we don’t see and that can only draw the gaze irresistibly to the search for clues that might support the hypothetical manifestation.

by Alexis Lussier

Originally, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death consisted of eighteen dioramas made during the 1930s and 1940s by Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962), founder of Harvard University’s Department of Legal Medicine and honorary police captain of the New Hampshire State Police. These stunning dioramas, made from dollhouses for didactic purposes, were reconstructions, on a 1:12 scale, of crime scenes and murder scenes, to be used to train future investigators to “read” the details of a scene and establish the pertinence of facts through analysis and interpretation.

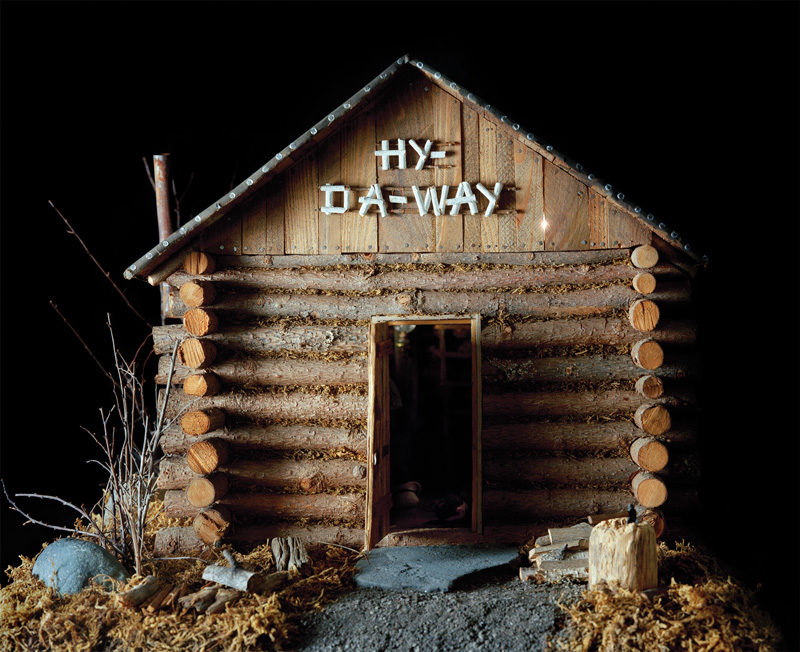

In her project of the same name, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, Botz has produced a series of close-ups of Lee’s dioramas as if they, too, were interior spaces, private places, haunted by death in spite of the very careful rendering of daily life. As if opening a shell, a box, or a drawer, the photographs literally take us into “crime sites” while reminding us, as do the letters “hy-da-way” affixed to the tiny log cabin, that we are seeing something that is hidden away and what we find there is not supposed to be opened or revealed. Hideaway is also a place to hide – a hideout.

In casting a photographic gaze at Lee’s dioramas, Botz can’t help but call into question the analytic objectivity of forensics as she dramatizes the scenes by using framing effects, amplifying colours, or upsetting our sense of proportion. Also prominent in these photographs is a certain blurred quality to the framing that highlights a prominent detail, and that has the effect of subjectifying the close-up while making the image seem like a vision or dream – something whose form isn’t completely apprehended. For instance, the close-up of the doll’s bloody head, by somehow flattening the perspective, gives the impression not only of a murdered body but of an aberrant body. Even more unsettling is the positioning of the doll upside down in a bathtub, its crushed face under an immobile flow of fake tap water, while the shapeless white slip makes a stain in the middle of the image. It’s a way of reminding us, because the cadaver is in a bizarre position, that the photograph is always also a photograph of a fallen body, which has become a messy thing.

In casting a photographic gaze at Lee’s dioramas, Botz can’t help but call into question the analytic objectivity of forensics as she dramatizes the scenes by using framing effects, amplifying colours, or upsetting our sense of proportion.

All of these effects displace the gaze at Lee’s houses to isolate single images and place them within the register of ambiguity. It is true that these eighteen miniatures are striking for the almost obsessive concern with detail and the quality of the reconstruction – which, in fact, only increases our discomfort with the fundamentally strange nature of the scene. Here, even the overall views are always in a tight shot. Everything is too small and at the same time bizarrely enlarged, amplified. For Botz has photographed not only the image of the murder or the crime scene that is represented, but, sometimes, a pair of slippers, a toilet, or a mantelpiece above which appears a too-large and almost-suspect red rope. These are pieces of incriminating evidence or clues to the very strangeness of a place that is no longer to scale now that the photograph has captured it.

If the crime and the messiness of a bloody doll are not always shown, it is because the less we see, the more we imagine. The feeling of proximity to the crime seems to produce a sort of influence on the place; the intuition of the tragedy envelops each object with a sort of aura that makes the scene particularly uncomfortable. And yet, if we are irresistibly disturbed, if there is a residue of uneasiness, it is also because the association between the methods of forensics and the world of dollhouses inevitably makes us look toward childhood. No matter how objective the reconstruction, these murdered dolls, this overturned furniture, the presence of a weapon or a body stretched out on a bed can only turn the innocence of dolls toward the feeling of an internal assault or a latent hostility. How many children have played at killing their dolls – or, at least, at doing violence to them – if only to break the tranquillity of an imaginary place that is often too peaceful to interest them?

Translated by Käthe Roth

Corinne May Botz lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. In her work, she investigates the perception of space and our emotional connections to architecture and objects. Her photographs have been internationally exhibited, including in shows at Wurttembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart, Germany; Bellwether Gallery in New York; and the Center for Contemporary Art, Torun, Poland. She is the author of Haunted Houses (Monacelli Press, 2010) and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death Monacelli Press, 2004). Botz received a BFA from the Maryland Institute, College of Art, and an MFA from Bard College. She teaches photography at theInternational Center of Photography and John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. Botz is represented by Bonni Benrubi Gallery (New York City). corinnebotz.com

Alexis Lussier is a professor in the department of literature at UQAM and a researcher at FIGURA, Centre de recherche sur le texte et l’imaginaire. He teaches modern and contemporary literature, psychoanalysis, and the function of the gaze in its relationship with the unconscious. He is currently preparing a research project on the imaginary of the criminal body, notably in the field opened by photography.