[Winter 2014]

Our field of vision determines what and how we see, and photography, it is thought, expands this field. Built into photographic technologies, however, are aesthetic and ideological conventions that shape our images and our interactions with them. In Andrew Wright’s survey exhibition at the University of Toronto Art Centre, his preoccupations with ontologies of optical technologies and representational systems were evident. Using a mix of historical and contemporary photographic technologies, Wright engages then disengages with what these technologies do best – realist perspective. His images, made with camera obscura, camera lucida, pinhole camera, iPhone, and video rocketry, defy pictorial expectations and allow alternative visualities to surface.

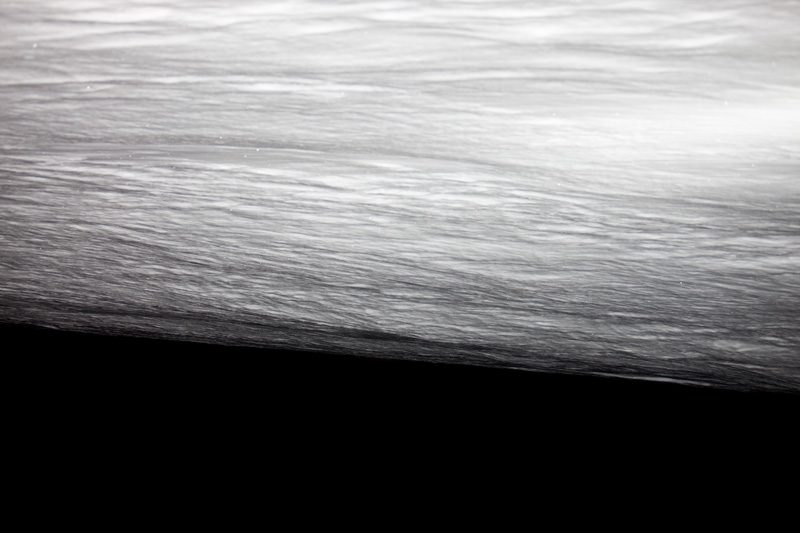

The exhibition title, Penumbra, reflects the visual ambiguity that Wright seeks: spatial and tonal relations are confused. The startling details in two giant negative prints, produced when Wright turned the gallery’s spaces into camera obscurae, are more magical due to their reversed tones, suggesting the primitive thrill that viewers of this optical phenomenon experienced centuries ago (When Buildings Take Pictures of Themselves, 2013). The camera obscura images in Skies (2003–04) are random frames of captured clouds passing overhead, taking us back to the times of William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, when photography was understood as “nature writing itself.” After Kurelek (2013) is a stunning Arctic panorama inspired by the painter William Kurelek’s depiction of white snow. A stark white mountain cut sharply against black Arctic sky becomes abstract when presented upside down. The artist’s playful tinkering with diverse media is encapsulated by a group of five mixed-media pieces that revolve around the depiction of clouds. What appears to be a historical photogenic drawing was produced with an iPhone app; the “cloud” in a wet-plate collodion image was sculpted from a crumpled paper towel.

As well as pictorial conventions, social values are built into optical technologies. In the 1950s, Kodak provided “norm reference cards” depicting white models with “normal” skin tone. South African artists Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin appropriated and combined these portraits with grey scales. The inability of Kodak film to render dark skin tones reveals its chemically constructed colour bar. A series of billboards titled To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light were seen in Toronto’s multicultural neighbourhoods.

Technological developments made the ubiquity of photography possible today. Democratization of the image, introduced in stages by Kodak, mass printing, and converged digital media expanded image production and dissemination, and, thus, our field of vision. Some thinkers – notably Walter Benjamin, who optimistically considered the political potential of “mechanical reproduction” – have welcomed these developments. But the resurfacing of the world with images raises another question: how to make meaning within this pictorial Tower of Babel.

The Dutch artist Erik Kessel reflects on photographic proliferation within social media spaces. Kessel’s Contact Gallery installation, 24hrs in Photography, is a mountainous terrain constructed of one million printed Flickr uploads. Unleashed here, these personal treasures become promiscuously available – we walk on them, voyeuristically stooping to snoop. Here is the debris of compulsive image capture, a tsunami of floating Kodak moments, literal fields of vision littered with the dead who shed their skins to make their own monuments.

Whereas Kessel makes sculptural fun of digital excess, the German artist Michael Schirner expresses the power of mass media images. In Pictures in Our Minds, white text on black background describes iconic photographs on billboards: “Naked Vietnamese child fleeing after a napalm attack”; “Marilyn Monroe poised over a subway air-shaft.” So strongly impressed are these images in our minds that only a textual trigger is required to set them ablaze.

With the increased volume and value of photographs came the archive. The original focus of Thomson Reuters’s Archive of Modern Conflict was twentieth-century war photography, but the archive has since expanded to over four million pieces in diverse genres and media. For the exhibition Collected Shadows at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, curator Timothy Prus culled 250 images from that vast collection and thematically clustered them in salon style. Pleasures could be found here for those who revel in interpretive challenge, especially since there was little written information to provide clues. Finer delights were found in the tiny poetic resonances that sparked between quirky juxtapositions. Curiously coupled with an albumen print, Bloodstain on Carpet, Belgian Judiciary Service (1881), was a small, round cyanotype, Woman on a Lonely Road (1900). The mixing of such disciplines as ethnography, botany, art, and journalism in the exhibition invited viewers to travel back in time to the early days of photography, when practitioners from various fields gathered together around the process, before the medium was segregated into different subject areas.

Photographic technologies are integrated with our cultural and aesthetic values and have led to the proliferation, collection, and archiving of photographs. But those who press the shutters also shape our field of vision.

The Art Gallery of Ontario’s photography archive that was started in 1977 now contains more than fifty thousand works. Curator Sophie Hackett fulfilled multiple goals with Light My Fire: Some Propositions about Portraits and Photography: celebrating the collection; making over two hundred works available for public viewing; and providing a historical survey of media and styles through the portrait genre. But it is Hackett’s careful sewing of meaningful threads between works that is most interesting.

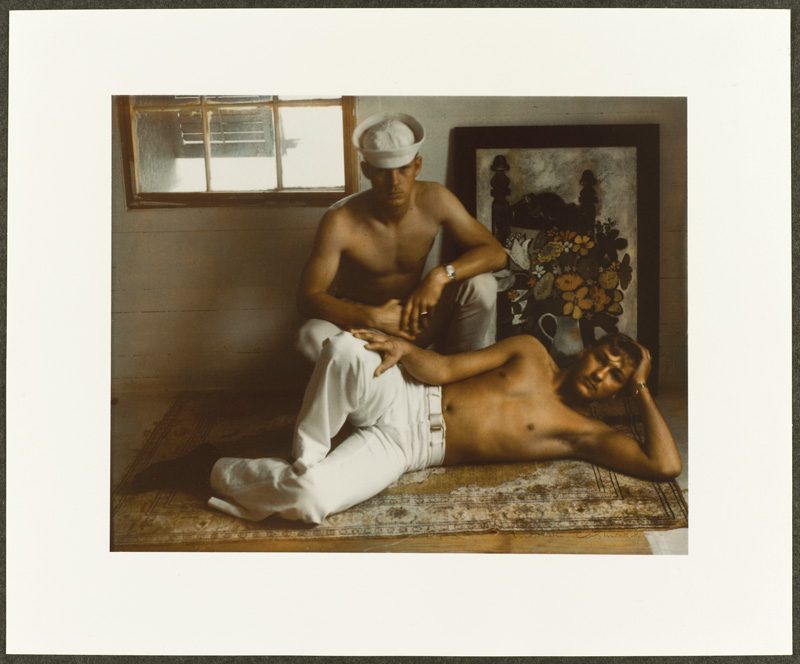

An introductory room makes a lively interplay between processes and periods: an ambrotype of a drawing of Charlotte Brontë and a tintype on stitched fabric mount are objects very different from Kessel’s Flickr ephemera. A large Cibachrome print, My Bed, Hotel La Louisiane, Paris (1996), is a photograph that any of us might take, but Nan Goldin’s lens presents it as masterful gravitas grounded in classical composition, with fruit spoiling on a brown paper bag as Dutch vanitas. Two images are paired in homoerotic suggestion: an elegant cyanotype portrait of Canadian sculptors Florence Wyle and Frances Loring (Robert Flaherty, 1914) hangs beside the seductive image of two young sailors, posing languidly in the warm embrace of Marie Cosindas’s dye-transfer print, Sailors, Key West (1966).

The following room makes rich commentary about our motives for photographing others – we come to our subjects with love and creativity or armed with a controlling, scientific gaze. Julia M. Cameron’s soft-toned albumen print La Santa Julia (1867) turns its back on Jacques-Philippe Potteau’s rigid ethnographic catalogue of Asian “specimens” (1860s) that lines the walls behind.

Hackett’s curatorship ignites with a row of Arnaud Maggs’s self-portraits that stretch across a back wall and converse with their surroundings. In After Nadar (2012), Maggs becomes the mime Pierrot famously photographed by Félix Nadar. In each of the nine large and meticulously made colour images, Maggs, gentle or grave, presents his life’s passions: Pierrot the Archivist examines another self-portrait from his earlier days; in Pierrot in Love Maggs holds a perfect bouquet of pink roses; in Pierrot Receives a Letter the artist’s gaze falls upon a black-lined mourning envelope held before him, the kind he himself collected and photographed.

Rich connections are made between this work and the adjoining sections, We Are Monuments and We Are Multiplied: Maggs’s work is multiple both in its seriality and in its relation to Jacques-Philippe Potteau’s classificatory style, a style that was later systematized by Alphonse Bertillon for police archives; Maggs was inspired by Bertillon’s method and adopted it for his own front- and side-view portraits. But, like Cameron, Maggs was an artist and used that rationalizing style for creative purposes. The series is also monument; made shortly before his death, it was, along with his Ryerson Image Centre exhibition, the sad heart and soul of Contact this year. Around another corner from Maggs’s multiple monuments are three black-and-white photographs of ancient but very realistic bodies; preserved instantly under Vesuvius’s molten shower, they were made into monuments – just as photography, through another method, embalms its subjects in light.

The prize for the Scotiabank Photography Award that Maggs received at last year’s Contact included an exhibition at the Ryerson Image Centre this year. For Maggs the collector, this was a suitable venue, as it is the site of the archive of the Black Star Collection and more than 2,700 other photographic works. Here too, the connections multiply among the five pieces that the artist selected: André Kertész: 144 Views (1980) is a 360-degree rotation of portraits of another significant photographer, following the format of Nadar’s Revolving Self-portrait (1865). In After Nadar: Pierrot Turning (2012), Maggs again entered the picture as whiteface mime, and with each turn he gave slices of himself, as had Nadar and Kertész before him.

Heightening Maggs’s profile at Contact further was the première screening of Spring and Arnaud, in which directors Marcia Connolly and Katherine Knight gave a glimpse into Maggs’s relationship with the artist Spring Hurlbut.

Photographic technologies are integrated with our cultural and aesthetic values and have led to the proliferation, collection, and archiving of photographs. But those who press the shutters also shape our field of vision. The Royal Ontario Museum presented Sebastião Salgado’s exhibition Genesis, a body of black-and-white photographs of landscapes and seascapes, animals and people. To these subjects, “unchanged” for tens of thousands of years, Salgado applied the powerful aesthetic that he had used in his earlier projects, Workers and Migrations. The majestic landscapes recall Ansel Adams’s fine prints and Edward Weston’s abstract compositions. Although many of the images are beautiful and compelling, the extravagant presentation of 245 needed stronger editing.

It is, of course, fascinating to see landscapes that few have access to and people whose lives are so different from those of museum visitors. For example, Salgado lived with the reindeerherding Nenets in northern Siberia for three months, so we have a glimpse of their arduous lives. But, although Salgado’s is not Potteau’s classificatory gaze, it is the peering of National Geographic: close-ups of exotic primates and village chiefs in tribal costume hang beside each other in the gallery.

The exhibition text states that Salgado’s subjects were untouched by Western culture, neglecting to clarify the different degrees of contact that they had had. The romantic distinction between pure, idyllic communion with nature and contaminated modern culture was more rhetorical than honest. Even if there had been no contact, could they remain “untouched” after their encounter with this photographer? The people in the Brazilian village of Zo’e helped Salgado build a studio out of leaves to provide a more uniform background for compositions. In one of the most striking – but constructed – images, ten women and girls relaxing in hammocks or applying pigment to their naked bodies are arrayed across a pattern of shining leaves. Is this so different from the much-critiqued French Orientalist paintings of Arab women lounging in Turkish baths? Salgado’s Genesis also recalls Edward Curtis’s pictorial and staged photographs of indigenous people of North America. Rather than the ecological innocence of Genesis, it is Salgado’s unique field of vision that prevails. A further complication is that although Salgado’s purpose is to show what remains untouched by environmental destruction and to inspire its preservation, this costly eight-year project in thirty-five locations was sponsored by Vale, the Brazilian mining company notoriously voted the worst corporation for human rights and environmental credentials in a 2012 Public Eye poll.

A more intimate relationship with the land was seen in Marlene Creates’s survey exhibition at the Paul Petro Gallery. Unlike Salgado’s aerial views of monumental mountains and glimmering waterways, Sleeping Places is a series of close-framed shots of the artist’s body’s impression on patches of grassy earth, taken in Newfoundland and Scotland.

Meryl McMaster’s In-Between Worlds (2008–13) at the Katzman Kamen Gallery was a sophisticated exploration of the relations between indigenous and colonizing peoples. The young artist showed interdisciplinary skill in ten large chromogenic photographs of her performance installations, making poetic statements about colonized indigenous bodies and cultures. In Terra Cognitum, draped circles of strung beads demarcate regions on the artist’s prone body that suggest topographic map markings. In Wingeds Calling, McMaster, dressed as a raven laden with small birds, moves through a snowy landscape. This artist’s occupation and manipulation of the space of the other is more complex than Salgado’spure peoples and places.

Vision is but one of our senses – but, to paraphrase Walt Whitman, it is large and can contain multitudes. Our fields of vision are expansive, and can be filled anew. Each year, Toronto’s Contact festival helps us do this: it also asks us to think closely about what enters that field.

Jill Glessing is a writer, artist, and teacher of art and cultural history at York University and Ryerson University.