[November 23, 2021]

By Louis Perreault

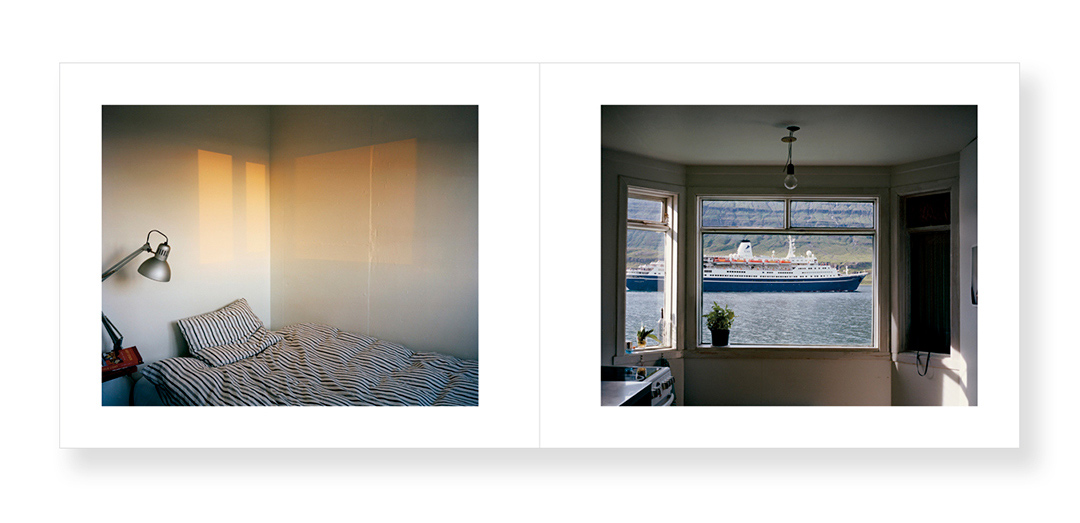

In Jessica Auer’s most recent film, Shore Power, one scene could act as prelude for Looking North1. We see a large window, opening out to a calm body of water. After a moment, on the right, a huge ferry appears and then crosses the image very slowly. What is striking at first is the immense size of the ship. An off-screen voice reads a tourist guide relating the transformations in local communities since the explosion of mass tourism in Iceland, where the scene is filmed.

This same view of the Seydisfjördur fjord, in eastern Iceland, is also in the book Looking North, this time as a fixed image. It is juxtaposed with an interior view in which we barely make out the trace of light from the window on the opposing wall. Captured in the studio belonging to Auer, who now divides her time between Iceland and Canada, these photographs seem to want to indicate that her approach is rooted in personal and direct observation of the tourism phenomenon, a subject that she explored in the project that made her name, Re-creational Spaces.

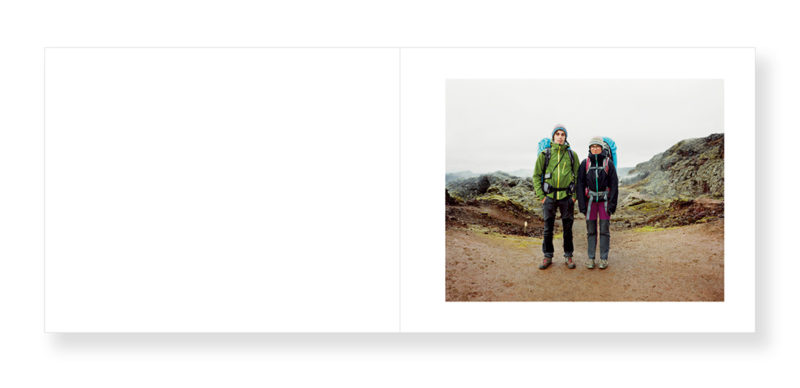

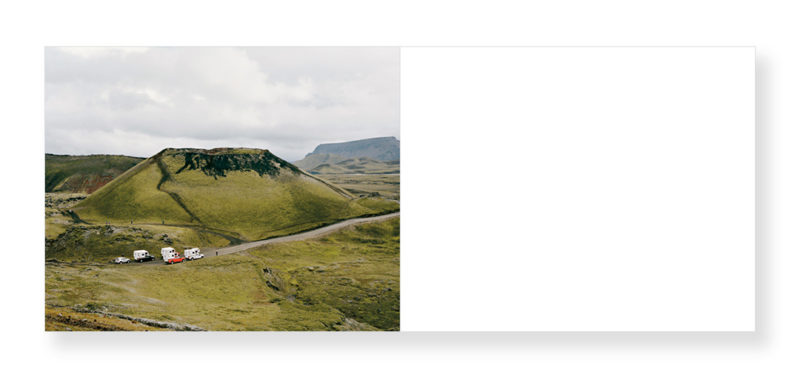

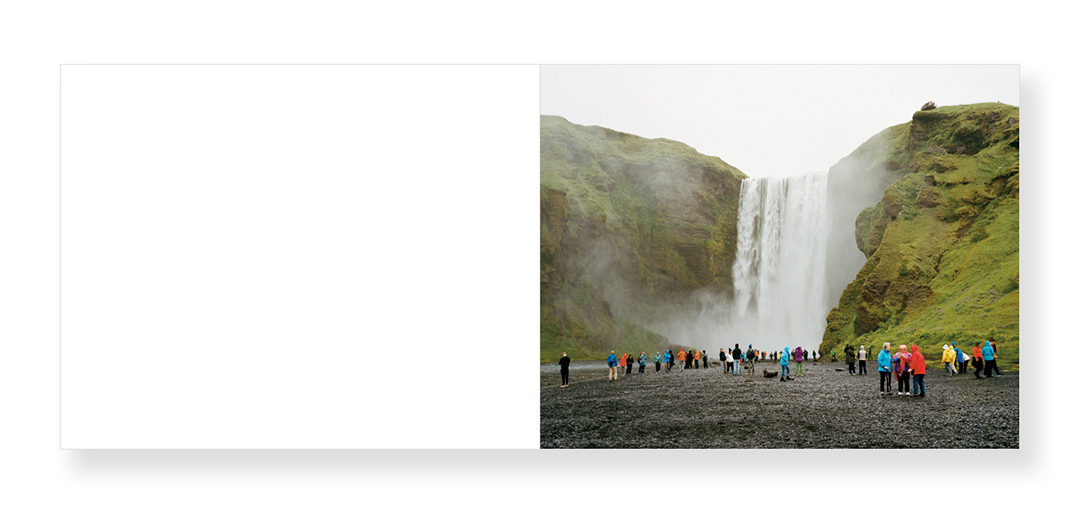

The series of images in the book shows places of extraordinary beauty – mountains, grassy plains, impressive waterfalls, inviting hot springs, steep cliffs. Each, however, is marked by the insistent presence of tourists – seen here in groups, there scattered around, and farther on alone, probably seeking a more private experience of the scenery. Tourist buses, groups of parked bicycles or motorbikes, and crowded tent encampments all indicate just one thing: Iceland, with its undeniable natural attractions, is now merchandised for tourism. Such series of landscapes showing anonymous occupation of the territory by tourism are related to Auer’s previous photographs, but it is the addition of portraits of travellers that makes this project new and particularly interesting. We knew that Auer was capable of composing landscapes comparable with those of the greatest contemporary landscape artists, but in this series we find a fascinating cohabitation of places by those who experience them. In the direct and extremely precise style that characterizes all of Auer’s work, the portraits humanize tourism and force us to recognize in these faces, poses, and gazes, inhabited by the joy of discovering the marvels of travel, the experience that almost all of us want to have – that of discovering a vast and awe-inspiring world. Although the point of the book is certainly critical of the tourism industry, Auer’s gaze avoids condescension toward those who feed the industry; rather, through simple and direct documentation of her subject, Auer throws into relief the contradictions behind many of our individual and societal aspirations.

Looking North is a modestly designed book; the choice of a small illustration of a fishing boat stamped on a cardboard cover evokes the industry that once reigned in the country. The images succeed each other without necessarily creating a series or developing a particular story. The book functions more by addition, as the photographs produce their effects by accumulation. Repeatedly seeing these places flooded with visitors strengthens the impression that their invasion is major, even disturbing. Readers who appreciated the mixture of direct observation and personal narration in Auer’s two preceding books (Unmarked Sites [2011] and January [2017]), will find this book simpler but no less effective and engaging. Translated by Käthe Roth

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.