[November 30, 2021]

By Louis Perreault

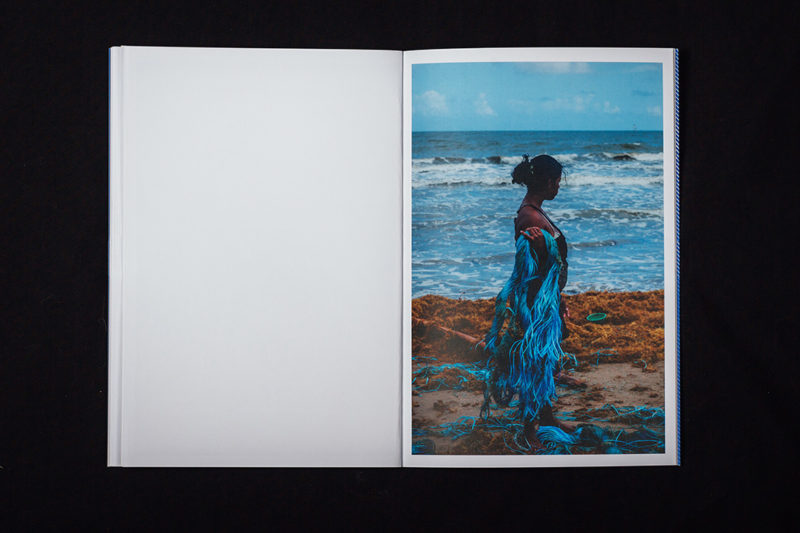

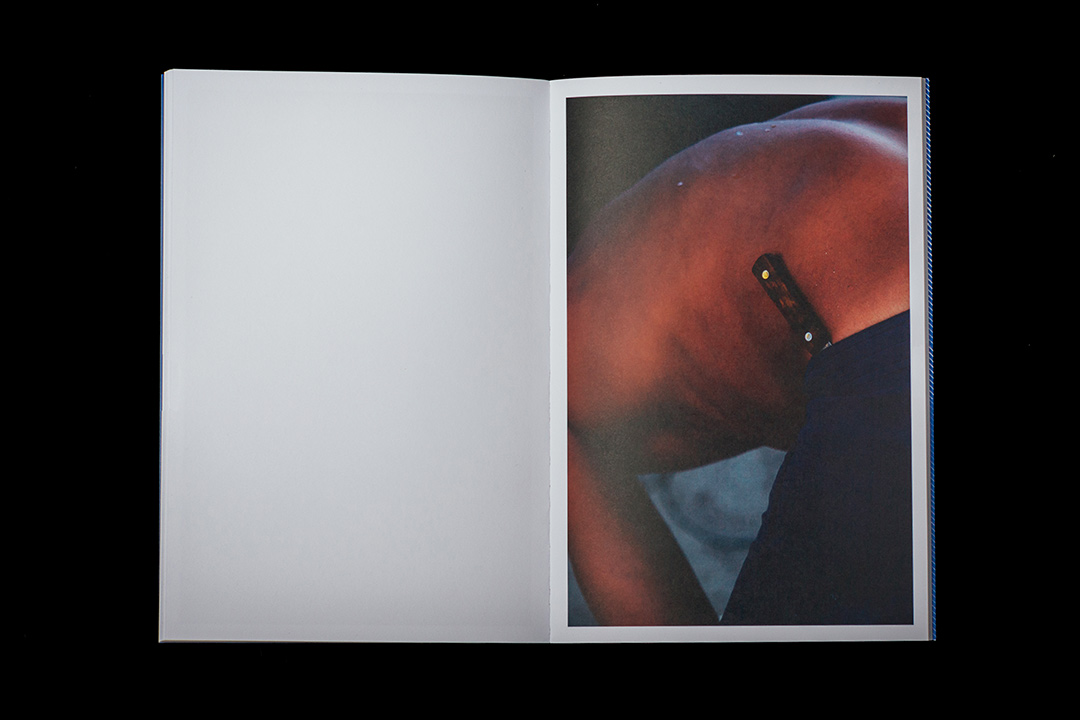

In Mosquitia, a coastal region in northeast Honduras, the “woman of the waters,” better known locally as liwa mairin, reigns. The daring men who dive into the depths of the Caribbean Sea to catch sea cucumbers and other fine edibles too often pay the price of her curse – an expression of her displeasure that her amazing lobsters and other clawed creatures are being scooped up. But this curse is no folk tale or legend; it is the tragedy of sudden paralysis caused by the formation of air bubbles in the bodies of these deep divers, who are poorly equipped and risk their lives for paltry wages.

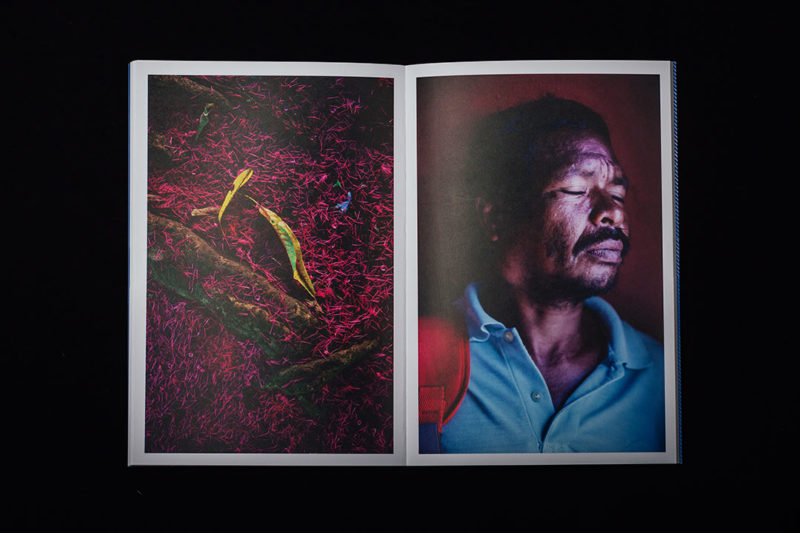

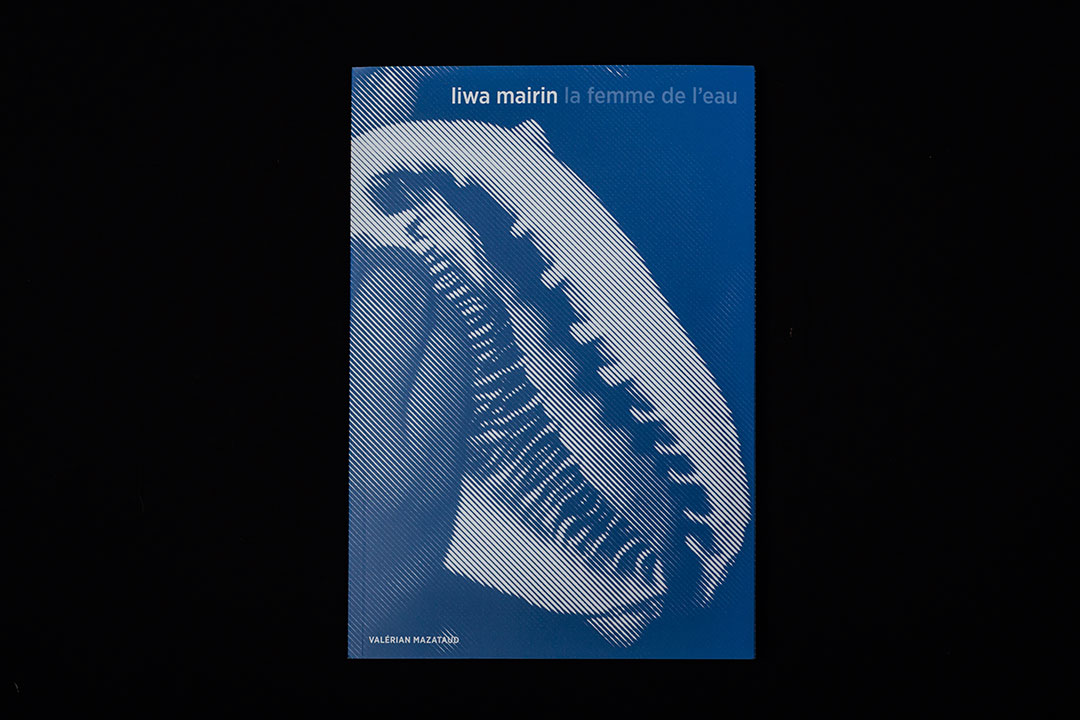

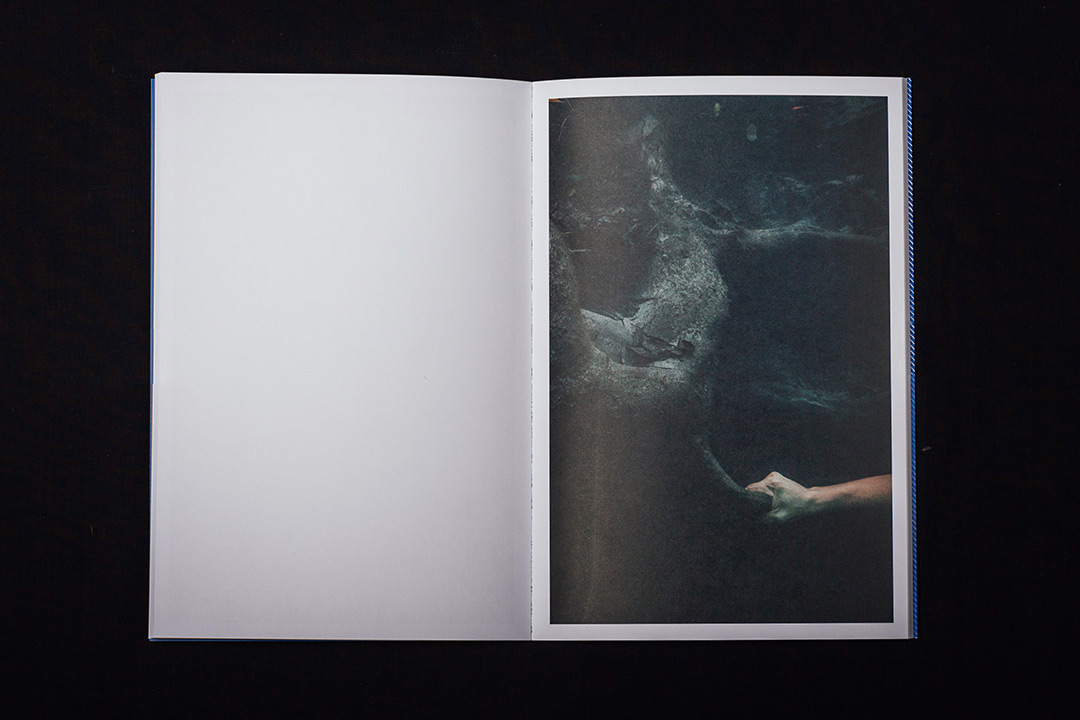

liwa mairin is a book1 that bears on its shoulders the huge task of portraying a complex social, economic, and human reality and visually conveying all the narrative and symbolic scope of the legend whose title it borrows. With surprisingly few images – under thirty of them – Valérian Mazataud achieves this objective. The anonymous individuals who we see throughout the sequence are part of a non-linear narrative; their postures, gestures, and closed eyes invite us to meditate on the fate of the divers, who live in a space marked by both tropical beauty and mourning.

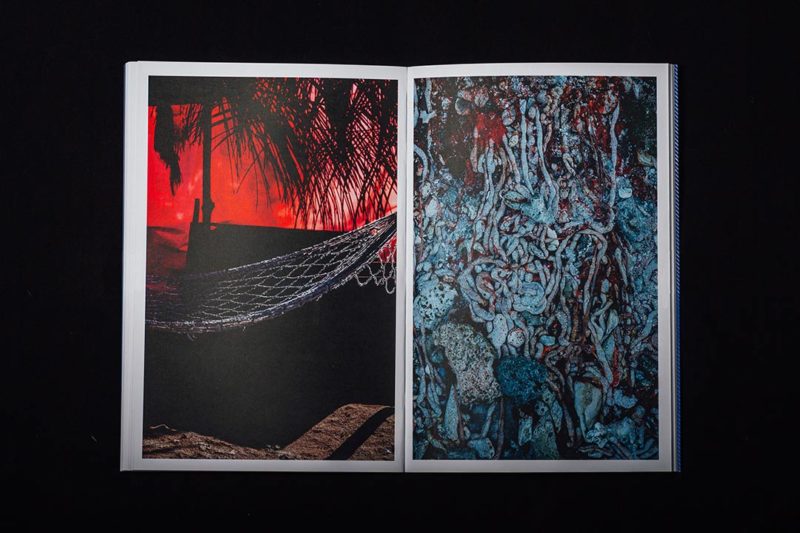

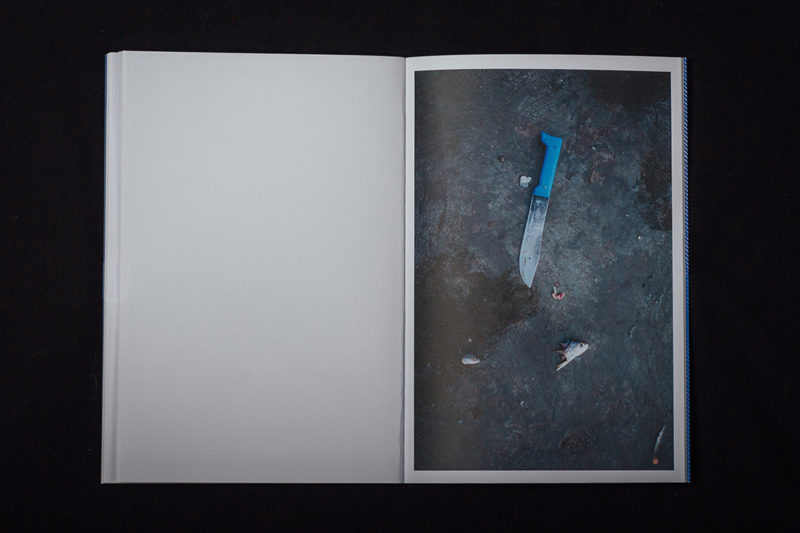

At first glance, however, the uninitiated might wonder, what are these capsules with round portholes, and who are the men hidden behind the glass, seemingly asleep in darkness? What is this woman, bathed in soft light and eyes lost in reverie, thinking about? At the very end of the book, where is this man going, resolutely staring straight ahead? These questions can never be answered fully, as Mazataud has chosen to use the photographs for their evocative potential rather than for the concrete information that they may offer. Therefore, the book walks a tightrope between photographic reportage and visual poetry. At times, we might wish to be told all about these scenes, but we cannot help being carried away by the dreamlike world portrayed in the series of images.

Whether on land or underwater, Mazataud chooses us to lead us into his story through bits of information. Objects and people are isolated in these images, forcing our imagination to connect the dots scattered like stars in a constellation. In fact, it is only when we look back, after finishing the book, that we can see its form. The omnipresence of the sea, fish, and diving equipment certainly provide reference points. Yet, Mazataud enlightens us only in a concluding poem that recounts the legend of liwa mairin and the story of the tragic fate of Marvin, drowned “at the end of the 150 feet of pipe that linked him to the surface” attached to “a mouthpiece from which a few bubbles rancid air escaped.”

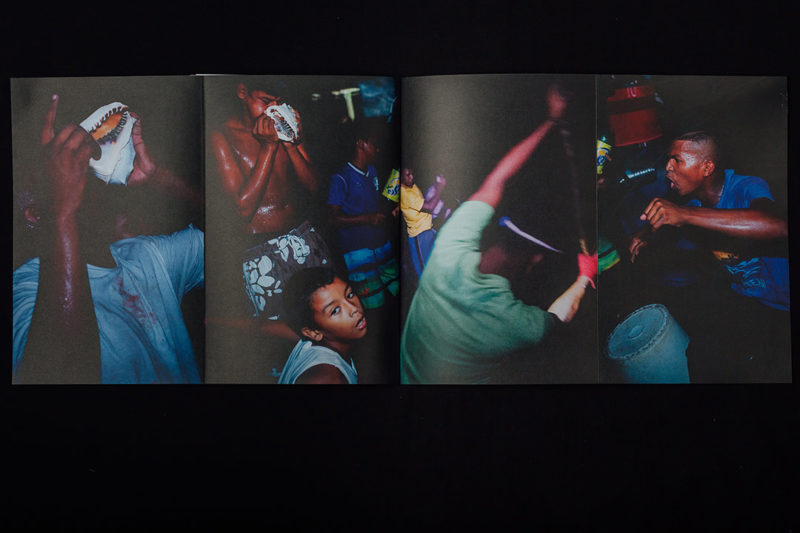

As we do with other books that draw the source for their intentions from both reality and imagination, we appreciate liwa mairin even more by repeatedly returning to its sequences, and some of us will even search further, beyond the book, to learn more about the realities of Honduran fishermen. And so, it is in the back-and-forth between the factual and the poetic that the essence of our reading will be revealed. In the centre of the book, for example, a series of images on pages folded inward immerses us in a moment of unequalled intensity. We see men and boys blowing into large shells, or dancing and hitting improvised drums. Although it is certainly easy to imagine that the group is simply enjoying a night off and celebrating the end of a fishing season or another seasonal event, it becomes difficult, after reading through the book, to not see it as a sort of incantatory ceremony, calling upon the woman of the waters in the depths of the ocean who rules ruthlessly over the great blue and all its creatures. Translated by Käthe Roth

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.