[December 21, 2023]

By Alain Depocas

Ne m’oublie pas. Collection Jean-Marie Donat

Entre nos murs – Téhéran, Iran 1956–2014

3.07.2023 – 24.09.2023

Year after year, the always-stunning Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles offers a heterogeneous program without any significant thematic grouping. Nevertheless, certain exhibitions stand out. In 2023, this was the case for Ne m’oublie pas, a presentation of images from Jean-Marie Donat’s collection,1 and Entre nos murs – Téhéran, Iran 1956–2014, composed of photographs found in an abandoned house. The significance of these two corpuses emerged less from the context of initial production than from the revelation fashioned by their curators.

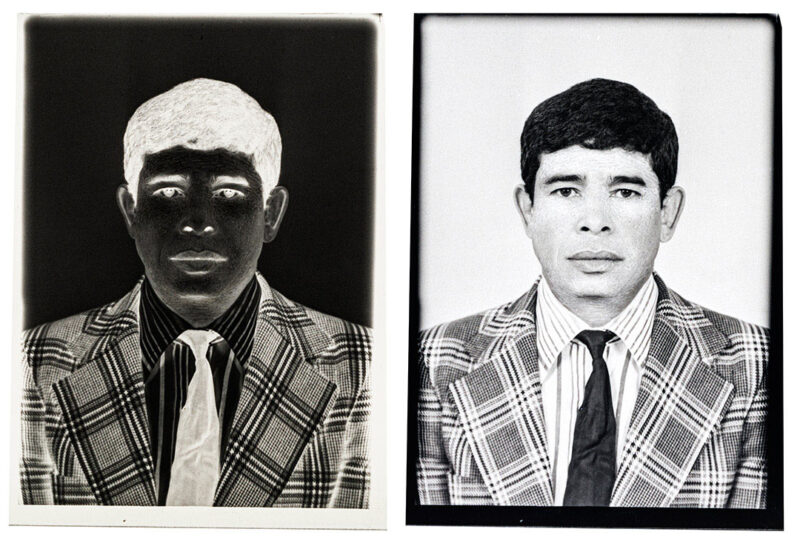

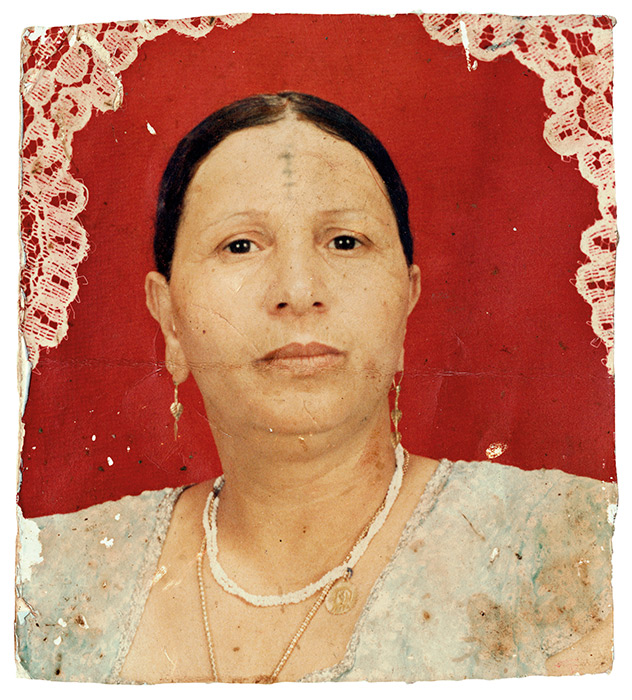

Curated by Jean-Marie Donat himself, Ne m’oublie pas2 brings together more than two thousand images produced between 1966 and 1985 by Studio Rex, a small family company situated in the working-class Marseille neighbourhood of Belsunce, where immigrants landed either to stay or to move on. Thousands of foreigners, mainly from North Africa and the sub-Saharan region, went to the studio, established in the 1920s by Armenian refugee Assadour Keussayan, to have identity photographs taken so they could obtain their papers. Aside from photographs in this standardized format, produced for administrative purposes, the exhibition includes three types of images: studio portraits, with sets and props; photographs of families that had remained in the home country, carefully safeguarded and intended to be enlarged, retouched, and colourized; and photomontages that combine these with more recent portraits to create simulations of family reunions and even weddings.

The exhibition’s scenography highlighted both the amassing and the singularities of the images. Entire walls covered with lightboxes presented hundreds of negatives, forming mosaics of small anonymous portraits that reduced individuals to standardized subjects and evoked bertillonage.3 The quantity of images in itself added a dimension; as Donat wrote, “It is the accumulation that ends up making meaning.”4 These groupings, in which a repetitive difference – or, rather, the repetition of difference – was manifested, were contrasted against enlargements of portraits that broke into the seriality and brought individuals surging forth. A few views of the studio itself, as well as artefacts such as boxes of silver-based photographic paper, reiterated these large formats and brought to mind the context in which the images were produced.

The poses and settings in the studio photographs also formed a counterweight to the serial anonymity. These images, meant to be sent to loved ones who had stayed behind, could be interpreted according to the props in the composition. A suitcase might point to a return home, whereas a coat might mean that the subject had adapted to the European climate. The most poignant images were the retouched and colourized family portraits: they impart all the emotions that they held for those who had taken the trouble to hold them close. Highlighted and enlarged, their power is enhanced.

Paradoxically, most of these images were on display because no one had come to pick them up at the Marseille studio. It was their abandonment by their owners, perhaps already departed for elsewhere, perhaps unable to pay for them, that made the collection possible.

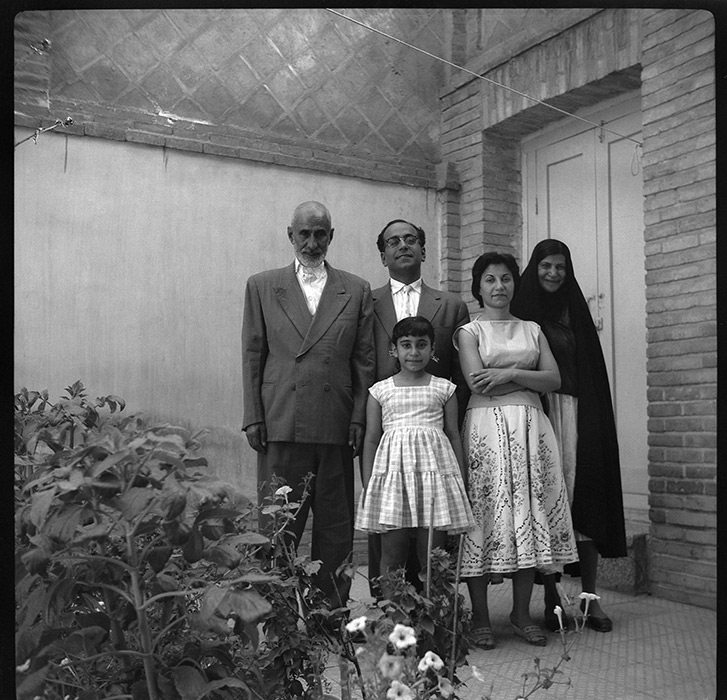

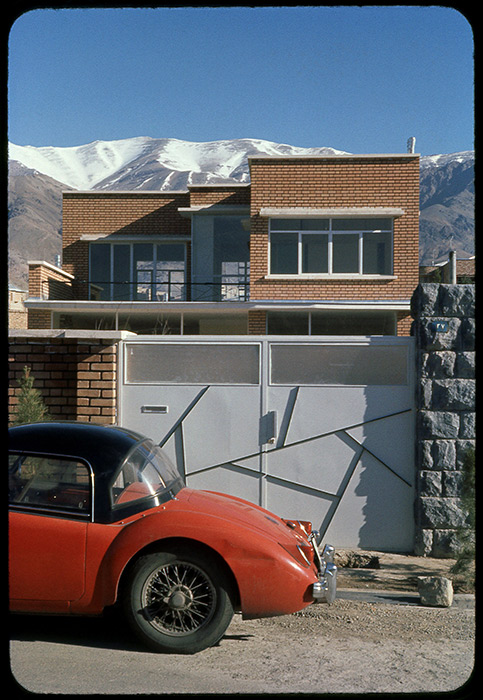

Before the revolution. Produced by Sogol & Joubeen Studio, Entre nos murs – Téhéran, Iran 1956–2014 featured photographs taken by an Iranian family between 1956 and 1979. This period, during which a family home was built and lived in, ended when the Islamic revolution began. Parents and children fled abroad, abandoning the house and its contents, hoping to return one day.

It was in this very house, about to be demolished, that the exhibition’s curators, Sogol Kashani and Joubeen Mireskandari, discovered the photographs. They inventoried and preserved numerous objects, including a trove of family snapshots and home movies, records, and magazines. The collection revealed Iranian reality at a time of ambient Westernization and reflected a way of life that stopped abruptly in 1979.

The exhibition was designed in the image of the house – or, rather, as a function of its traces and of the documents and artefacts that now represented it. The exhibition opened with a photograph of a man in the middle of a field; he is standing where the house will be built. Then came pictures of the site and of the finished project; as the years passed, the family, and the vegetation, grew. The display was complemented by a model of the building and a timeline highlighting key moments, from its construction to its demolition and its replacement by a highway and apartment buildings – the consequence of constant expansion of the city. The exhibition showed both the life of a house and a family’s and the vestiges of a forever bygone time – that of Western-style social aspirations in Iran before 1979.

Kashani and Mireskandari noted that they wanted the exhibition to be a “little museum” of the house. They explained their approach as a sort of investigation, using archaeological and other methodologies. They excavated the site, recovered objects and furniture, and used these artefacts, as well as the correspondence left by the family, to reconstruct an era in what resembles an attempt to exhaustively exploit the vestiges of a disappeared domestic space. The final project will consist of reconstructing the house as it was, including its furnishings – a sort of ultimate exhumation, of real representation.

The genesis of Entre nos murs – Téhéran, Iran 1956–2014 is different from that of Ne m’oublie pas, but the exhibitions share similarities. In both cases, the curators used reinterpretation to endow photographic corpuses with meaning. These exhibitions present “fragile” assemblages – photographs abandoned by their creators and their subjects – saved from oblivion.

What do these two exhibitions say about the photographic image? It is quite difficult, considering each image individually, to remove the indicial function, to ignore how the camera records reality. But these faithful traces, once accumulated and grouped into an organized corpus, compose complex narratives in which the precarious connections of memory and the threat of forgetting are revealed. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The title comes from a sentence written on the back of a photograph.

3 This was a technique for identifying criminals developed by French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon in 1879; it was based on biometry and photography.

4 Le Monde, July 1, 2023 (our translation).

Alain Depocas studied art history at the Université de Montréal. The subject of his master’s thesis was the various approaches to theorization of photography and their paradoxes. He worked as a documentarist at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, then directed the Centre de recherche et de documentation of the Daniel Langlois Foundation. He was a program director at the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, before taking time to devote himself to developing a photographic practice.