The Garden at Night

Espace Lafontaine, au parc Lafontaine

from March 28 to April 29 2018

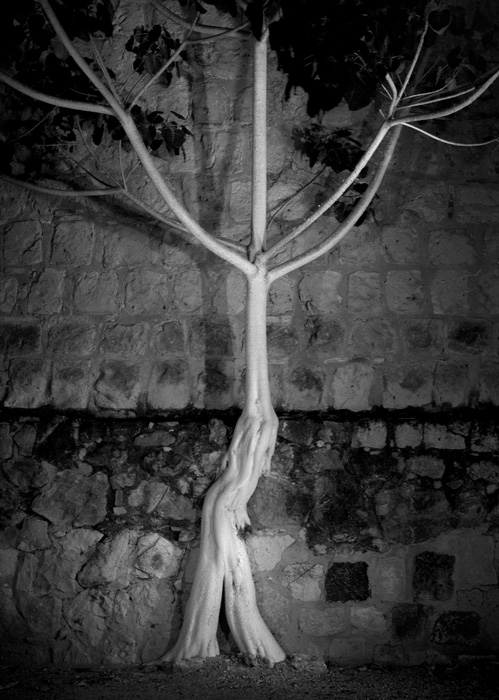

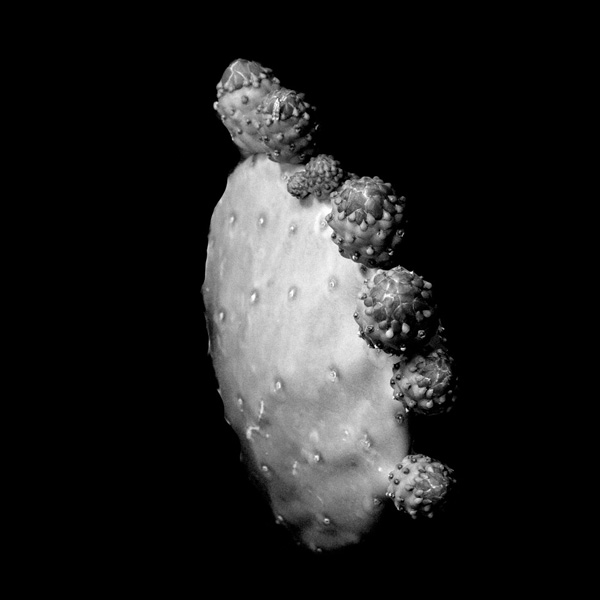

The Untamed Garden

Galerie Métèque, NDG

from May 31 to June 13 2018

By Christian Roy

Does the floral motif, so frequent throughout the history of art, still have a place in contemporary art? As a matter of fact, it did recur in a couple of Montreal exhibitions of the spring and summer of 2018. If one of these gathered artists in several mediums under this theme1, this motif will be dealt with here by dwelling on two other ones, that afforded the local public an overview of the body of floral work that secured photographer Linda Rutenberg’s international reputation. Already known among other things for her North American urban scenes, in 2006, she turned to an unusual project that would generate three books and several exhibitions, consisting in exploring at night (with the assistance of her late husband Roger Leeon for the lighting) some of of world’s most beautiful botanical gardens, including Montreal’s own.2

Starting in 2011, Rutenberg cast another familiar territory in an unfamiliar light, namely the scenic Gaspe Peninsula in the dead of winter, training her camera at brightly coloured objects mysteriously sticking out of the snow amidst daunting expanses of deserted landscape.3 In so doing, the photographer extended in reverse the path that had led her to The Garden at Night, where only flowers were artificially lit in the darkness. This long-term project embodied for her the essence of photography, since it started from the dark to make way for a luminous apparition —highlighted in colour by those of flowers. The enclosed garden’s dark space became the camera obscura as the casket for an object plucked from its own context to be set in another and showcased there, like a flower in a vase. In both cases, the eye lingers on the striking formal qualities of objects found in the middle of an environment that recedes in background shadow to leave them in the limelight. But is not the garden itself already the artificial framework of such a staging of fascinating and thus photogenic objects, made for this display? A flower is after all basically the vegetable kingdom’s best advertising gimmick, as a punctum of colour that stands out from monotonous greenery to catch the attention of insects for its own sexual ends which they know nothing of, just as it does not suspect the remarkable aesthetic effect that colours enhanced for the sight of arthropods also happen to have on anthropoids, driving homo sapiens to cultivate it in endless garden varieties.

Yet it is less neon signs in the night that Rutenberg’s flowers call to mind than exotic deep-sea creatures, caught in a beam of light in a dark abyss where their vivid colours and their outlandish shapes have no apparent meaning beyond this very quality as fleeting apparitions to the human gaze. It can no longer be superficial once plunged in an altogether different medium than that of picturesque floral displays —namely the acoustic space of an aquatic environment of sorts, conducive to the resonance of whatever sticks out of the thick ambient stillness. The shimmering bloom and the translucent leaf shine in its midst as the lighted tip of a sunken world of lush plant life, whose muffled throbbing it somehow dimly intimates as a synecdoche both visual and tactile. For the quality of the rendering, the subtlety of shadings bring out the pulpy textures, the lanky postures of extravagant and suggestive forms, quietly ushering us into the unsettling intimacy of glossy flesh, non-human to be sure, but whose languid vibe osmotically creeps into our animal sensorium by some kind of subliminal consonance. Likewise, at a more contemplative level, a kind of spontaneous mystery, of opaque, uncanny solemnity, unveils its tiny monuments in the geometric shapes of organs shorn of their function within the shrines of flowers stripped of their petals.

Sumptuary self-expenditure here lavishes the figures of life in night’s cosmic chasm, revelling in the waste of their slow fall into oblivion. Such was the desublimated “language of flowers” that, in 1929, Georges Bataille felt able to discern in the unsaid of Karl Blossfeldt’s close-up “portraits” of plants against blankly dark or grey backgrounds. These pioneering nature photographs were likened at the time for their magical realism to Max Ernst’s Surrealistic Histoires naturelles, a collection of collages and frottages that blurred boundaries between the human form and other phenomena. Rutenberg appears to be following in her own way this poetic drift into the decomposition and reshuffling of organic structures, as she returns to a wilder state of previously explored turf for The Untamed Garden, a new body of work whose first fruits could be sampled at NDG’s Galerie Métèque, next to older colour photos of public gardens as seen at Lafontaine Park. They differ from the latter by a bold use of black-and-white, at times up to a bright negative reversal of the nocturnal element, haunted by prickly livid forms that strain and split under stress from the forces of life and death as they mesh in swollen flesh and swirls of membranes. Linda Rutenberg shows herself ready to dive headlong into the tangle of plant matter of such a polymorphous eroticism, that finds in the night its secret garden.

Traduit par Christian Roy

2 Linda Rutenberg, The Garden at Night. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008; After Midnight. Burlington, VT: Verve, 2009; The English Garden at Night. London: Thames & Hudson, 2010.

3 Linda Rutenberg, The Gaspe Peninsula: Land on the Edge of Time, Montreal: Del Busso, 2014. See Bernard Lévy, “Linda Rutenberg. Des images découpées au scalpel”, Vie des Arts, No. 234, Spring 2014, pp. 58-61.