[February 7, 2024]

By Siobhan Angus

Recently shown in Toronto,1 Louie Palu’s Cage Call (1991–2003) is a kaleidoscopic portrait of life in the mining communities of northern Ontario and northern Quebec’s: work underground, union organizing and strikes, community events, illness and accidents, and funerals. Over twelve years, Palu visited eighteen gold and silver mines in one of the world’s most productive hard-rock mining regions. Unusually, Palu was granted virtually unrestricted access to several mines. His father, a stonemason, introduced him to the geologist Frank Ploeger, who worked at the Kerr Addison mine, and Ploeger helped him secure entry underground. He supplemented this initial access by attending union meetings and forging connections with workers, organizers, and community members. This slow work of relationship building enabled extraordinary access, resulting in the most comprehensive bodies of work on hard-rock mining since David Goldblatt’s On the Mines (1973). It is a testimony to the complexities of life in extractive regions, and the photographs are, themselves, physical documents of mining labour. Cage Call places mining at the core of modern life—and at the centre of the history of photography.

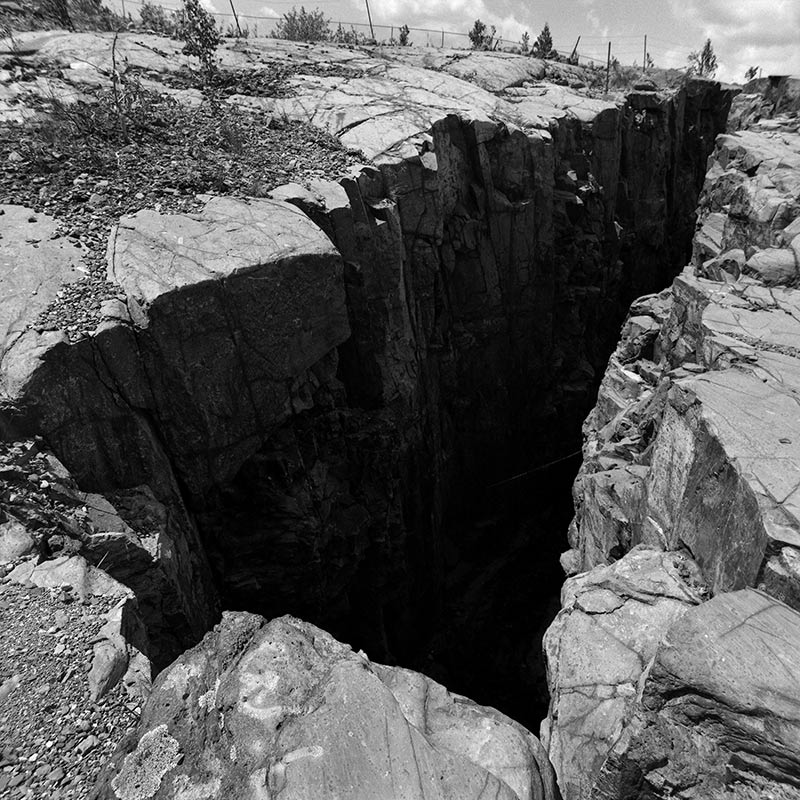

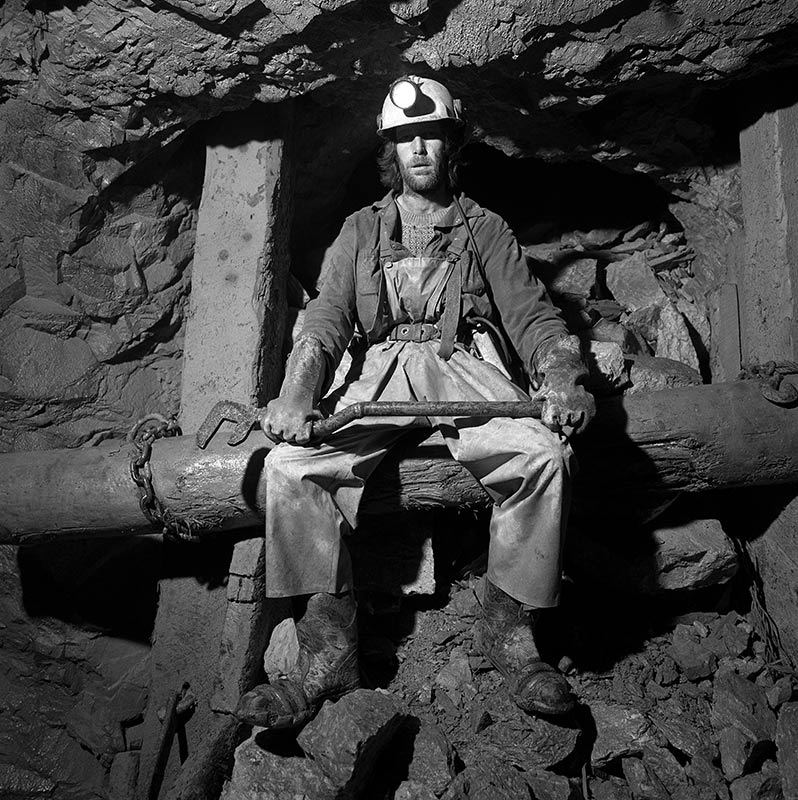

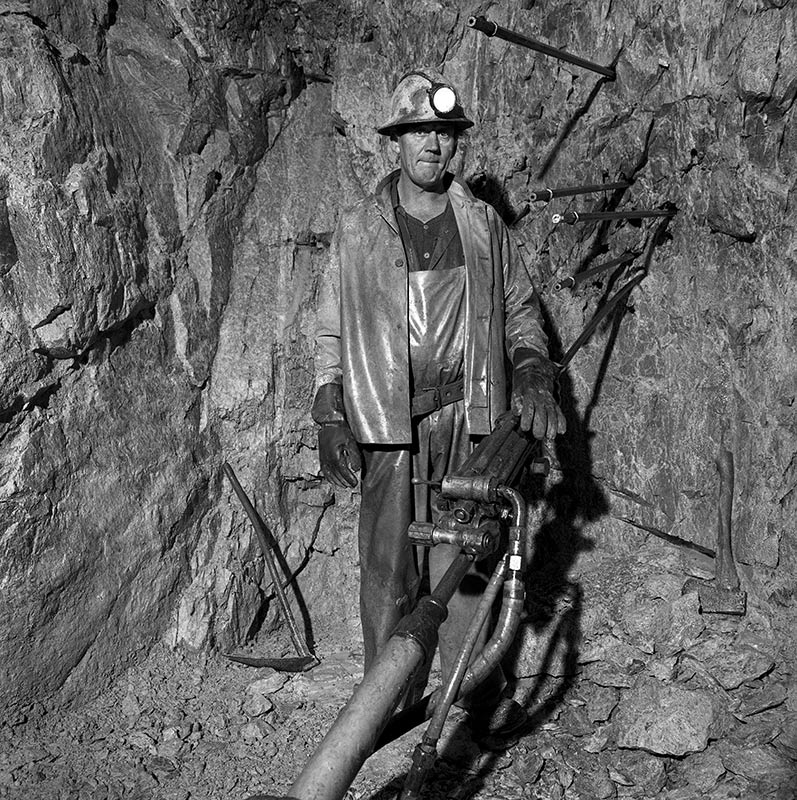

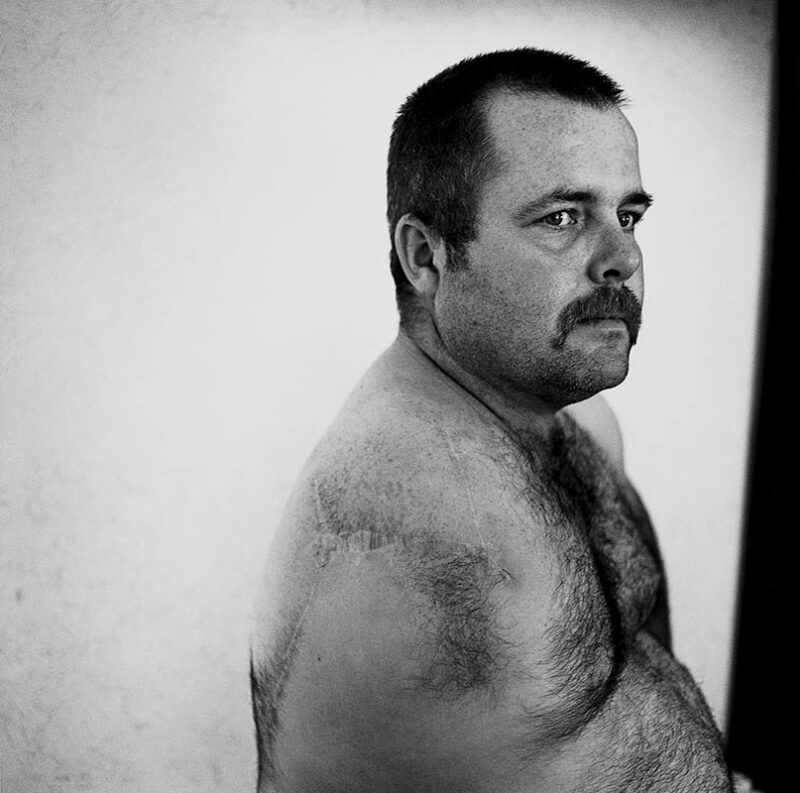

The underground photographs emphasize the darkness of the mine through high contrast and stark silhouettes. We see miners working and resting, some posed, some seemingly candid. Scenes of labour militancy emphasize the workers’ agency: on a picket line in Sudbury, a man poses with “Scab Hunter” written across his t-shirt. Finally, the shattered landscapes of mining form a parallel to the injured bodies of workers – both damaged by mining.

Documentary realism is the underlying impulse of the series, and the photographs are formally grounded in social documentary photography. Palu shot in black and white for practical reasons: colour film was expensive to process and print, and the dark underground workspace necessitated the faster speeds of black-and-white film. The subject matter also harkens back to a lengthy tradition of humanist photography. The mine has long occupied a prominent place in cultural imaginaries: it exemplifies the capitalist extraction of human labour and natural resources, making it a profound site for consideration of how the world is made. Although Cage Call aligns with a liberal-humanist tradition of the photograph as bearing witness, Palu’s body of work gestures at something more complicated.

Visual culture is deep in the throes of a turn to materialism, which has led to a resurgence in documentary photography in the last decade. As Sarah M. Miller shows in Documentary in Dispute: The Original Manuscript of Changing New York by Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland (2020), documentary is a complex and contested category. For instance, in her photographs Berenice Abbott sought to bring into view that which capitalism had repressed or disavowed; thus, through her use of documentary, she aimed to illuminate the hidden structures that order modern life. In Cage Call, Palu has a similar goal: to make two obscured realities visible. First, he attempts to root the abstractions of a global economy and stock market speculation in the labour that makes them possible. Second, he ties photography, as a medium, to the mine.

Exhibiting the images at the Image Centre is, in a sense, a geography lesson. The Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) is the global leader in mining financing. Three hundred mining companies are listed on the TSX, which finances over 40 percent of mining equity worldwide. In 2023, mining and minerals represented 25 percent of the top-performing companies on the TSX, with oil and gas making up an additional 50 percent. On the stock exchange, the pieces of earth extracted by miners are abstracted into speculative objects. Fifty years into neoliberalism, financialization has unmoored even the most tangential links among labour, material, and value. The 2008 financial crisis exposed the fundamental speculation and gross inequalities at the heart of contemporary economies and sparked a renewed interest in documentary realism. Palu’s photographs highlight a tension in contemporary understandings of documentary photography, prompting a question: what work does realism do in the context of capitalist speculation?

Palu also highlights a more elemental connection between the mine and the print: mined materials are essential for photography. Silver is crucial in silver gelatin prints, as raw silver ore is refined into light-sensitive silver halides. The raw materials extracted from the mine become the vehicle for documenting the mine. The photograph as an object is thus also a document of extraction. Palu proposes that mines – and the communities surrounding the mines – are critical components of the photographic supply chain. His fusion of the mine and photography invites a reflection on the complicity of artists and art institutions with the exploitative forces of global capitalism. He entangles photography itself with the mining communities of northern Ontario. Indeed, Cage Call makes a broad claim: Palu approaches Canadian mining not merely as a regional history or a glimpse into extractive labour but as being at the heart of contemporary life and, indeed, photography. Traduit par Frédéric Dupuy

Luigino Palu (Louie Palu) is a Canadian photographer and filmmaker who examines social political issues through a hybrid approach, incorporating art and documentary. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and a World Press Photo Award; his projects have appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, and the Dok Munich Film Festival. His work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the National Gallery of Art, among others. He holds a BFA from the Ontario College of Art and Design and an MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art. He is represented by the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

Siobhan Angus is an assistant professor of media studies at Carleton University, specializing in the history of photography and the environmental humanities. In her current research, she explores the visual culture of resource extraction with a focus on materiality, labour, and environmental justice. Her book Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography is forthcoming with Duke University Press.