[August 30, 2022]

By Louis Perreault

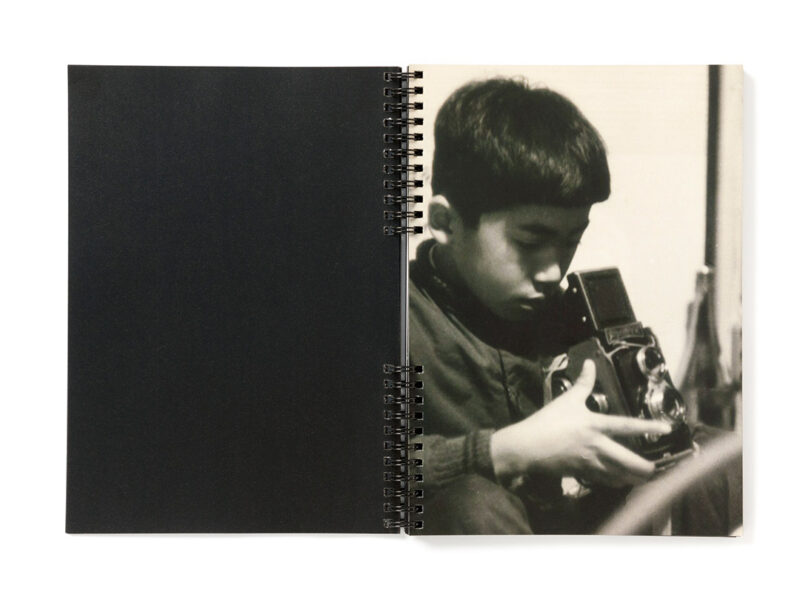

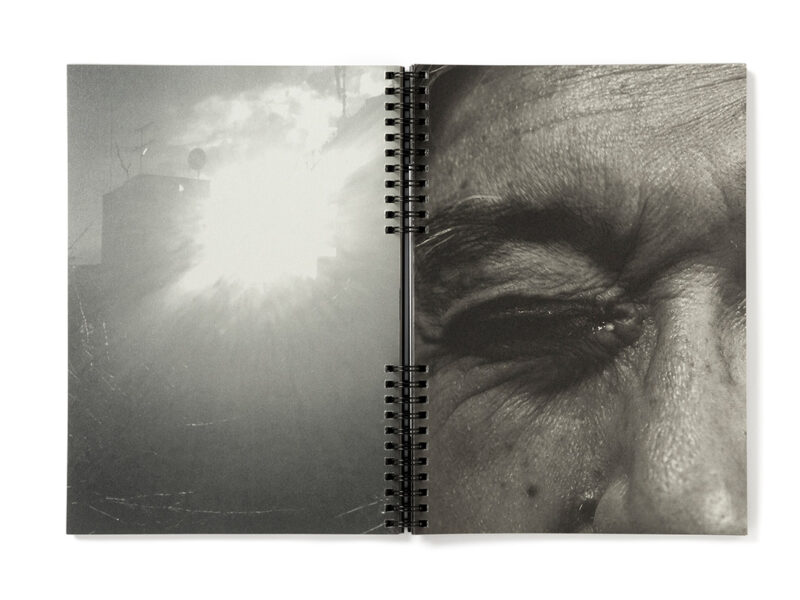

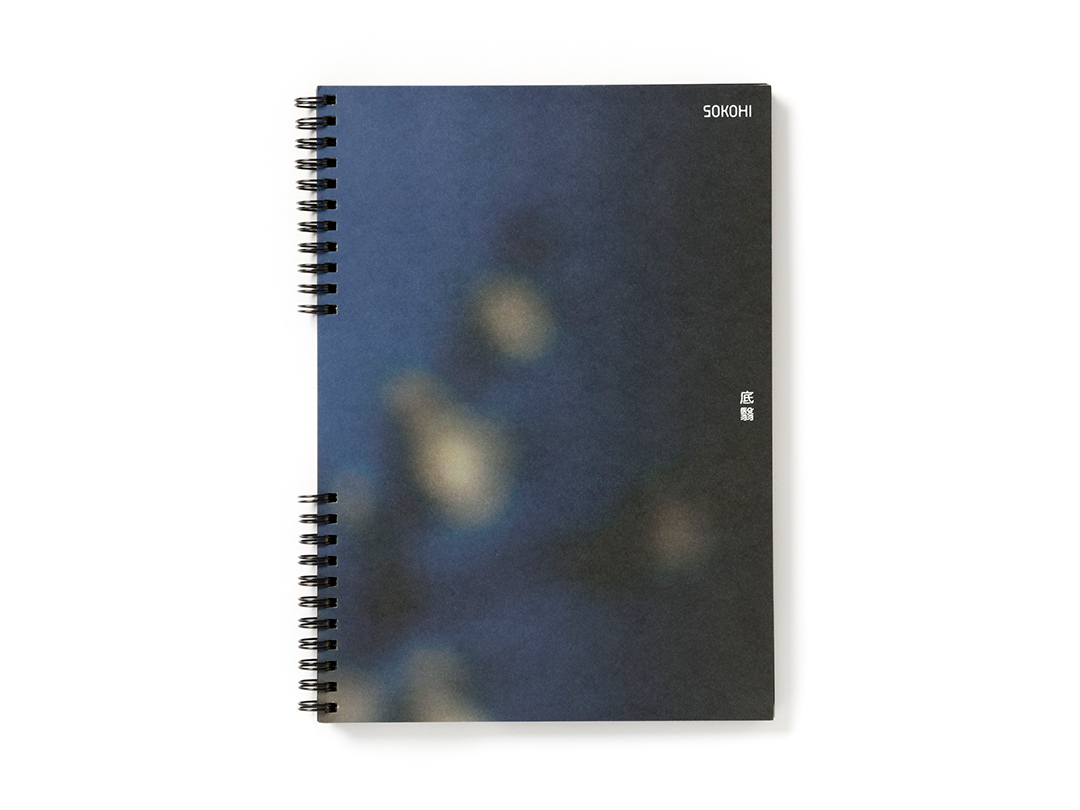

Opening the hard cover of Sokohi, which slides easily on the metal-ring binding, we discover the tight reframing of an archival photograph showing a boy’s eye. The sepia tone and the sparse traces of dust in the print transport us to a long-ago era – the inception of the sequence of images that unfolds before our eyes. This child, whom we will follow until he is an old man, is the protagonist of this intimate book, in which the Japanese artist Moe Suzuki follows her father’s journey into blindness, as glaucoma takes him to “the shadow at the bottom.”1

Moe Suzuki, Sokohi, Chose Commune, Marseille, 2022, 25,7 x 18,2 cm, 150 pages

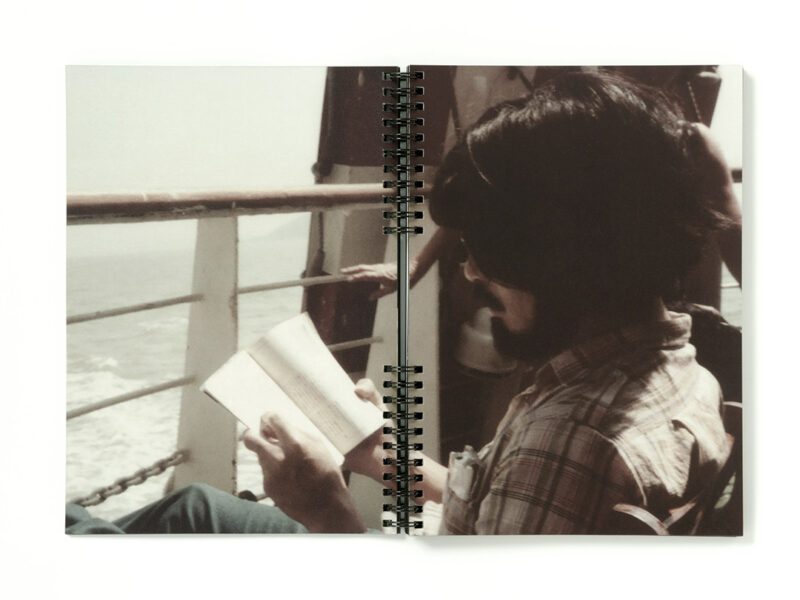

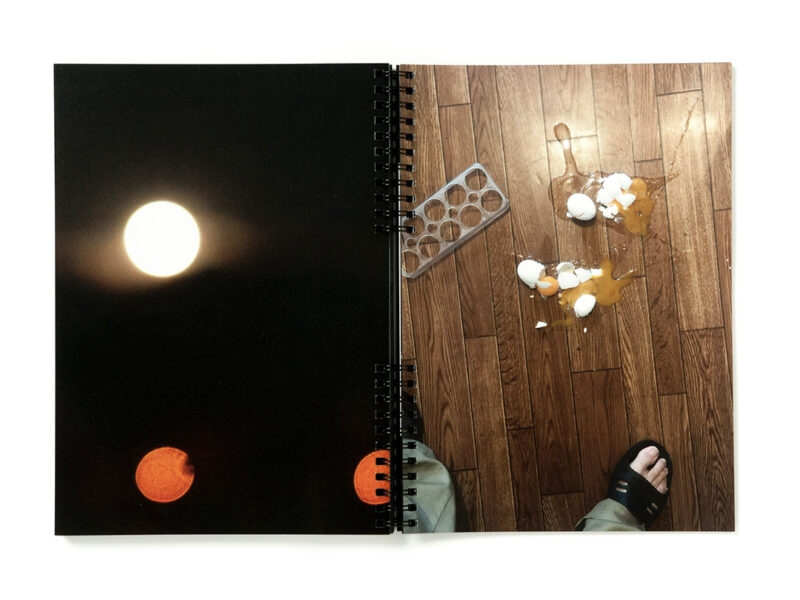

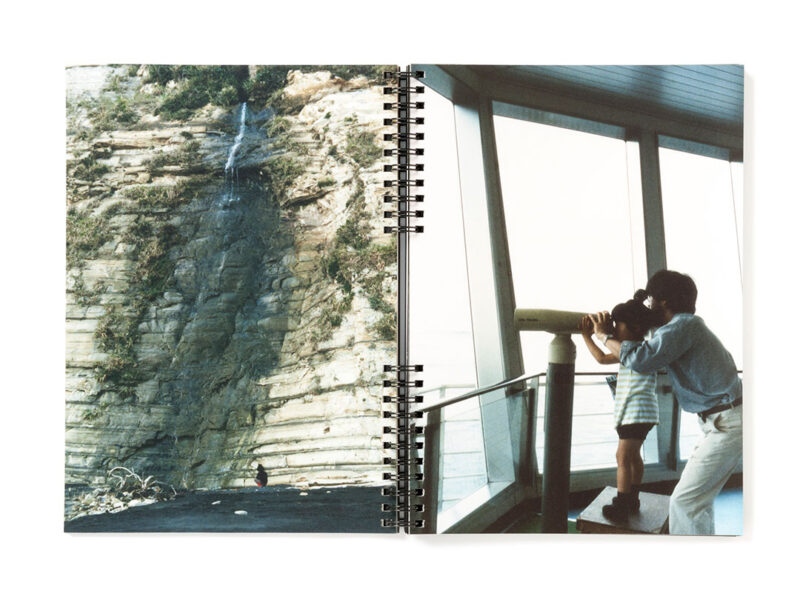

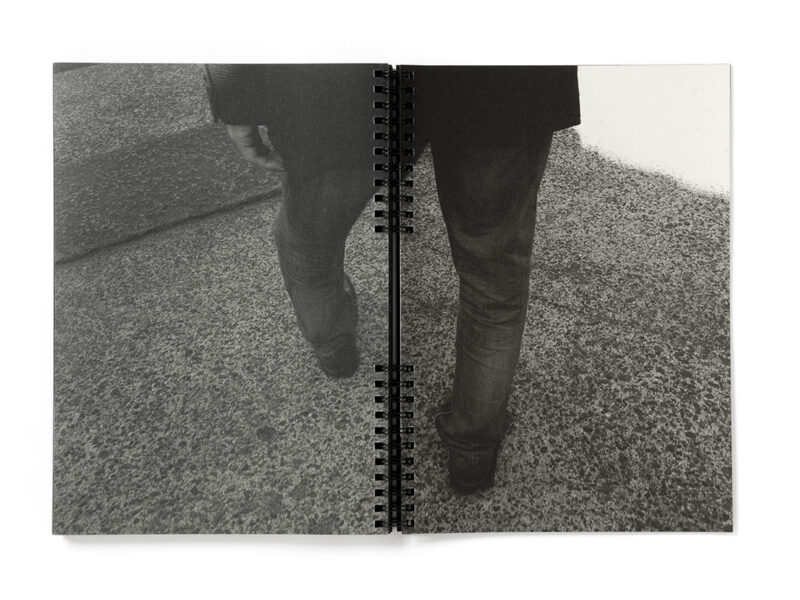

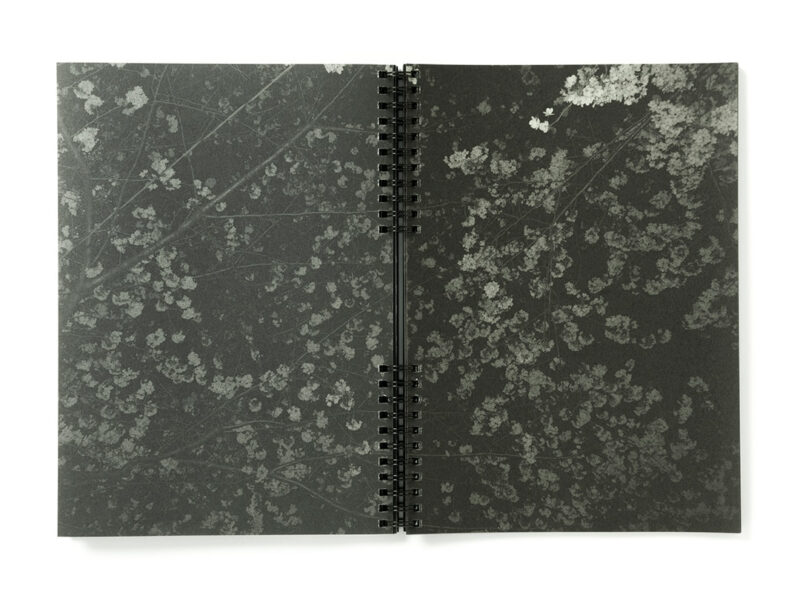

Composed of photographs found in family archives and images taken by her father or her, Suzuki’s book is an invitation to meditation, as we turn the full-bleed pages. In her delicate images, a vacillating light bursts forth, joltingly illuminating backlit scenes or softly dimming on the motif of blossoming apple trees. Through such details of nature and the city, we get to know the boy, who becomes a man and then a father, posing affectionately with his daughter as they venture to discover fleeting moments of everyday life. We find him at different moments, sometimes photographed in the hard beam of an uncontrolled flash, at other times in portraits made by his daughter the photographer, very likely sensitized by her trade to how essential the dimension of sight is to our experience of the world. Tetsuichi Suzuki, the man who is her subject, has spent much of his life surrounded by writing and books, thanks to a career of almost thirty years in publishing. As we discover through a short text written by Moe Suzuki to provide context for the images, photography found a meaningful place alongside writing in his private diaries, which he kept up his entire life. Yet, these visual and textual recordings of experiences and of life lived are now closed to him, and become evidence of a past that he can now return to only through memories and recollections.

Although a sense of the chronology of events stands out at first reading, an attentive study of the sequence surfaces the delicate and deliberate interweaving of different kinds of images – archival or produced specifically for the project. In recent years, a large number of photobooks have drawn on the evocative power of the archive for the source of a narrative, poetic, or conceptual project. The juxtaposition of images of different temporalities most often has the effect of breaking up the rhythm of the sequences, deliberately complexifying the reading.

In Sokohi, the succession of these different types of images operates differently, weaving ties of familiarity, rather than discontinuity, between past and present. As they are not distinguished in the layout, the archival images and Suzuki’s photographs intermingle naturally. She leads us into her father’s private world, which, we imagine as we look at these details of daily life, gradually become haunted by an increasingly invasive blur. There is a dialogue between the artist’s point of view and her father’s: although it’s obvious that Moe is photographing the man stretched out on the bed, the reading experience is enhanced by the play of projection in which we indulge as we look at the landscapes and weakly lit domestic details. Are we looking at what Tetsuichi can no longer see, or are these his last glimpses at these things? The beauty of this book resides in Suzuki’s ability to leave us in this undefined space of reflection, gliding through the surrounding darkness. In the end, the sombre tonalities dominating the images brilliantly express the feelings of fear, loss, and mourning borne by the one for whom the visible is slowly fading away.

First conceived as a limited-edition artist book, Sokohi drew attention through a series of competitions dedicated to photobook dummies2 and was the winner of the prestigious LUMA Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles 2021. The publishing house Chose Commune, based in Marseille, then undertook to collaborate with Suzuki to rework the original publication, notably doing away with a complex laser cut-out that certainly had its charms but was difficult to reproduce in a larger-scale production.3 Although a few aspects of the content and fabrication differ between the dummy and the published book, the latter retains the essence of Suzuki’s offering of a profound reflection on the visible that shares the sensory experience of the world by people with inseparable trajectories. Translated by Käthe Roth

2. Including: Fiebre Dummy Award, Spain, 2020; Kassel Dummy Award, Germany, 2020; Belfast Photo Festival, Ireland, 2021; and Mack First Book Award, England, 2021.

3. It is also interesting to view the video documentation of the original maquette, produced by Suzuki, which can be seen on her website, banyan-b-i.com/sokohi.

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.