by Suzanne Paquet

“Landscape” photography – that which depicts the territory, the environment, places – is no doubt one of the most widely practised photographic genres, by various categories of picture takers: topographers, explorers, artists, tourists, and amateur photographers.

It is also one of the most popular genres – for the very simple reason that many people incorporate it into their pleasant Sundays or pleasant trips. One might suppose that landscape and photography have been bonded together by a common principle since the mid-nineteenth century. Mobility is the basis of this commonality: like the landscape, the photograph engenders round trips between the thing and its image, and more than – or with – the landscape, it travels. The photograph is considered a place-holder, a view that one wants to share or that it is always possible to go and contemplate in its in situ version. It is seen as a miniaturized and transportable equivalent of the place that has, in addition, the faculty of encouraging movement. In this, it likely constitutes the exact response to the idea of landscape.

Photographs of territory have served various purposes, from the formation of national identities and geographic imaginaries to the display of the “exotic” and the promotion of travel, thus giving rise to vast inventories. Because they list everything and carry their subject with them – in this case, their site – photographs let us glance through the world, first as “armchair travellers,” then as strollers through cyberspace, which is not so different. Ensuring constant reciprocity between the geographic and the depicted, photography has thus greatly contributed to shaping an image of the world, making the world into an album that one can always flip through or examine. Now, images of every place, all known territories, themselves endowed with ubiquity – “existence in series,” Benjamin said – are within our reach; they come to us. This heaping of disparate places at a particular point creates a singular spatiality1, which may correspond to a form of despatialization – leading to a sort of timelessness, in which all places in the world are present in the present, undermining the old idea that a photograph had a particular time, a time characterized by a immediate, or sudden, gap between a too-early and a too-late.2

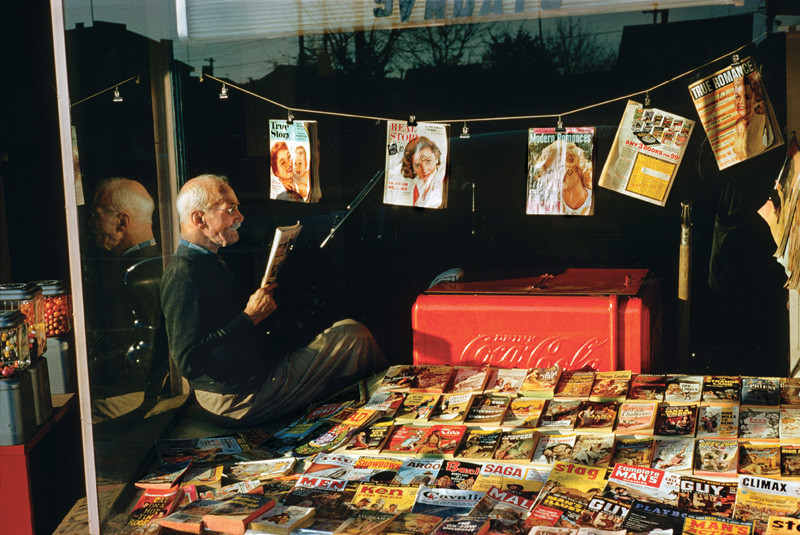

The landscape is, in itself, a thing that is mediated, even if solely by the gaze. It comes into existence only when human beings feel the need for nature, even as they are irremediably dissociated from it. The landscape is thus, to begin with, synonymous with nature, and it is city people who call for more natural views.3 Paradoxically – or, perhaps, logically – the “urban landscape,” according to many, should not be a conceivable category; yet, photography very quickly seized upon this inhabited, sometimes haunted, space, and it is depicted again and again. We look nostalgically at views of disappeared places taken by Charles Marville, Eugène Atget, and other nineteenth-century photographers, while today Stéphane Couturier, Fred Herzog, Robert Walker, Greg Girard and others speak to us of ruins, ghostly presences, foreign panoramas in which everything becomes a sign, but also of community, singularities, and dreaming as we stroll. The urban, the humanized, is a passion just as old, for photographers, as is wide-open nature, and it is a passion that is still very alive, by all evidence.

As for nature, through a sort of geopolitical shift, after decades of passionate engagement, art photography left it – or, rather, left it to tourists. Nevertheless, artists, fascinated by what tourists rediscover for us, bring a different gaze – sometimes even a dog’s-eye view as when Jana Sterbak walks Stanley in Venice – to sites that are too well known, overexposed in the media, or too fabricated, such as those depicted by Jessica Auer in her Re-creational Spaces.

But photographs of the outdoors are still very popular everywhere, as if images of natural sites could be reassuring in these times of environmental catastrophes. Wiped clean of critical views, the most prized photographs are those that are still and always an invitation to travel, to believe in a certain terrestrial spirituality; these are the ones that still have, in fact, the right to the term “landscape.” For artists, however, it is now a matter of scrutinizing the places of the world differently, of denouncing pillage – industrious and industrial madness – to reveal desolation, excess, the point of no return. In cities or devastated areas, at sites whose appearance reveals nothing of their toxicity, artists, having sought the signs of modernity, now seek those of post-modernity, the traces of brute power and the human condition in which the territory is a background and illustration. Can we then still speak of “landscape,” a cultural form that originated in nature and its contemplation? The photograph, like the landscape (or the idea that we have of it) was first considered an immediate – natural, if you like – given, which would enable images of nature to be spontaneously reproduced.4 Very soon thereafter, the question became that of an aesthetic or aestheticized object that could be manipulated, retouched – such as the vast collections of “ready-to-mount” skies by Gustave Legray or Eadweard Muybridge, or the irresistible “composite photograph” of a country landscape of Manitoba made at the Notman studio.5 And while, now, “the territory is a construct,” has become “a sort of artefact,”6 it is similarly difficult to conceive of an art photograph as a pure and simple sampling, discourse-free, stand-alone, unconnected. This is borne out by the works of Isabelle Hayeur, Ivan Binet, Edward Burtinsky, and Sylvie Readman, to name just a few of the artists who reflect the environment in its transformed, fabricated, artificialized, altered, devastated version.

Thus, to follow the shift in the idea of landscape, from the natural to the aestheticized to the shaped, we would invariably return to the photograph. But since all places in the world are visible from all other places, their photographic equivalents perpetually updated, can we, or should we, still pursue the landscape or its photograph? Can we, today, add to the inventory? Should photographs that examine the environment have the mission of creating a lasting discomfort? Can we gaze upon the territory in another way? Must we fabricate, following in the footsteps of many artists in the last two centuries, our own utopias? Or should we re-create the world, make heterotopias, construct other spaces, through photography? Such places would be in no place, except in the photograph itself.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 “It is the sudden vanishing of the present tense, splitting into the contradiction of being simultaneously too late and too early . . .” Thierry de Duve, “Time Exposure and Snapshot: The Photograph as Paradox,” October, No. 5 (Summer 1978): 121.

3 See André Corboz, “Le territoire comme palimpseste,” De la ville au patrimoine urbain. Histoires de formes et de sens (Montreal: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2009), p. 84.

4 As Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre said in 1839; see Historique et description des procédés du daguerréotype et du diorama (Paris: Alphonse Giroux et Cie, Éditeurs, 1839).

5 http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca/fr/collection/artefacts/VIEW-2507?Lang=2&accessnumber=VIEW-2507

6 Corboz, “Le territoire,” p. 73 (our translation).

Suzanne Paquet is researching the inscription of certain types of art – in particular, environmental art, public art, and photography – in the process of landscape, urban, and spatial production. She recently published Le paysage façonné. Les territoires postindustriels, l’art et l’usage (PUL, 2009). She teaches in the department of art history at the Université de Montréal.

RELATED ARTICLES

Greg Girard, Phantom Shanghai – Amish Morrell, Accelerated Ruins

Fred Herzog, The City’s Fabric – Helga Pakasaar, Free Observer

Jessica Auer, Re-creational Spaces – Michelle Kasprzak, Ways Out of the Labyrinth: The Works of Jessica Auer

Isabelle Hayeur, Paysages incertains – Suzanne Paquet, Quelques fêlures