[October 19, 2021]

By Johanna Mizgala

Tim Franco derived the title for his photographic project, presented as a book, from a term in George Orwell’s dystopian novel, Nineteen-Eighty-Four. In Newspeak, the officially sanctioned language of Orwell’s oppressive super-state Oceania, an “unperson” is an individual who has been not only executed but also erased from all public records. Eventually as a result, unpersons disappear from memory itself. Orwell drew his inspiration for being deleted from society from the Latin phrase damnatio memoriae – the damnation of memory. This term describes the conscious and deliberate act of obliteration of identity, acts of which can be traced well into the altogether distant past; as long as there have been public accounts, whether spoken or written, there have been ways to omit those whom, for whatever reason, have been deemed unworthy of being remembered.

In juxtaposition to this purging from the record, there is a Russian proverb that translates to roughly “You live as long as you are remembered.” If the things that we rely on to aid our memory, such as photographs or physical traces of existence such as a signature on a document, disappear, how can we trust historical accounts? If we know that records can be altered, manipulated, or destroyed, how does this knowledge change our understanding of identity and recollection, especially when the erased are present to tell their own stories?

In the case of Franco’s subjects, their accounts describe a double erasure, one of their own choosing and one that comes because of this choice. Franco’s portraits are of individuals who fled North Korea, each with personal reasons for doing so, and yet their particularities weave together a bigger story of a totalitarian state and the consequences of choosing to escape your home country. Franco employs the term “defectors” as a label but recognizes that this is problematic. There are complex reasons for leaving; although political dissent is certainly one motivation, others of equal importance are terrible living conditions, abject poverty, and an utter lack of opportunities or resources.

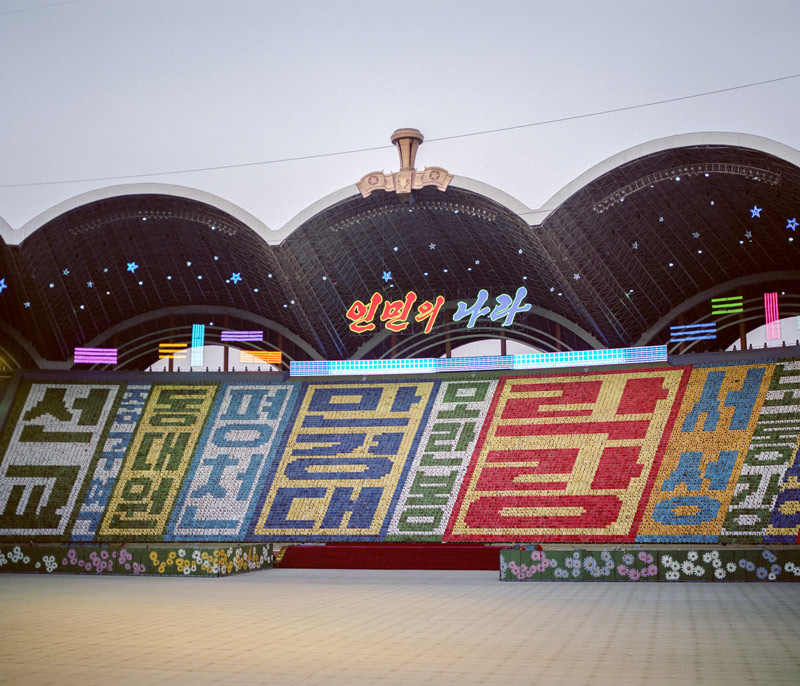

Each portrait appears in the book alongside the respective subject’s personal story, presumably as told to Franco. As their stories aren’t told as first-person recollections, the distancing effect of a third-person narrative reinforces their place within or without the official narrative of the country. As a complement to their stories, Franco has also included photographs of the landscape and border regions, as if retracing his subjects’ steps and underscoring not only the places they left behind, but also the journey undertaken.

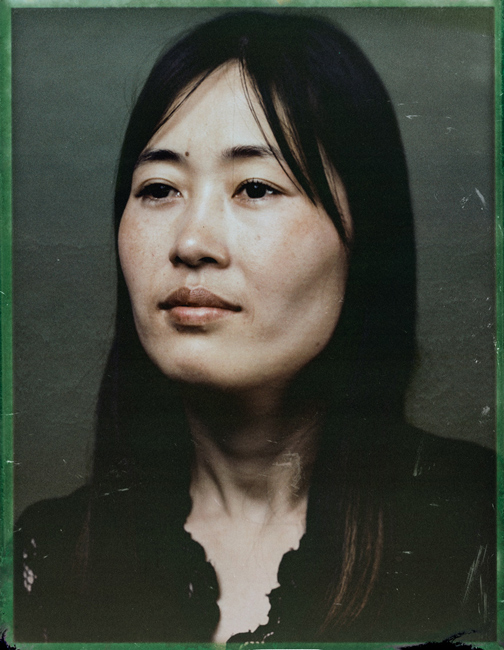

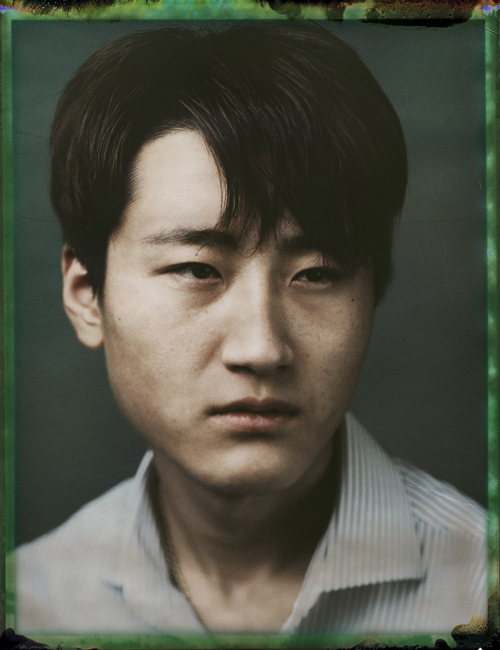

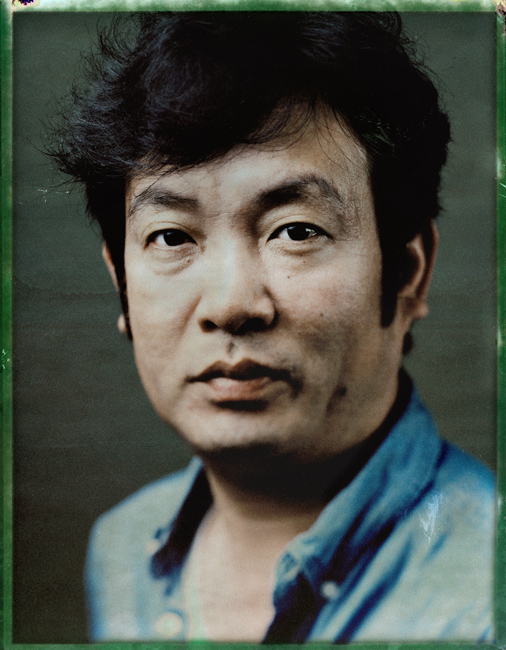

Each portrait is a tightly framed colour closeup against a non-descriptive background, making it somewhat reminiscent of an image study or an enlargement of an identification photograph. Therefore, the image itself offers very few clues about the subject, making each frame in turn utterly dependent on the narrative account for some idea about who each person is, what led him or her to leave North Korea, and the aftermath of this decision. The subjects exist in a kind of between space, forever defined by how they arrived in front of the camera. The images are compelling and yet, at the same time, passive and detached.

Franco describes his process as an analogue created from something that doesn’t or shouldn’t exist: a negative stemming from a Polaroid. It is revealed through a series of chemical washes that inevitably leave their trace on the object, so that it appears imperfect, worn, and he cannot ultimately be sure what will be uncovered each time he restarts the process. The resulting image bears the traces of its creation, and Franco likens this manifestation to his subjects – for, in truth, they are the product of their life story, and its traces can be felt in the contemplation of their faces.

Mike Beech has created a short film called Reclaiming the Negative, in which he follows Franco through a portrait session with one of his subjects, Eun-Ju Kim. The film is poignant for its intimacy, in that we hear Kim share her story in her own voice, albeit through an interpreter. The combination of hearing her voice and looking at her photograph is especially powerful in that it enables an encounter in time and space with one of Franco’s unpersons.

Throughout his project, Franco maintains the distance of an observer, although it is evident that he has been deeply moved by hearing his subjects tell their stories. In these portraits, there is a recognizable territory: a “space between.” This is not Franco’s own community and yet, perhaps because of his own identity as an outsider to this world, he is able to bring to light people who have been erased from their own space of being, who now exist in a between space of their own. This location is not of their choosing, while simultaneously being because of their choice to leave. Life literally goes on in North Korea, without them.

Born in Paris in 1982, Tim Franco spent a decade in Shanghai, where he documented the urbanization of China and its social impacts; this body of work was published as his first monograph, Metamorpolis. During that period, he developed his style, working mostly with an analog camera and trying to bring a minimalist aesthetic to documentary photography. Since moving to South Korea in 2016, Franco has contributed to Time Magazine, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, National Geographic, Le Monde, Geo, and others. www.timfranco.com

Johanna Mizgala has worked extensively in exhibitions and public programming, as well as teaching art history and cultural literacy, and as freelance art critic. She has lectured and published broadly on photography, photo-based art, museology, and architecture. She is a member of the Board of Directors of the School of Photographic Arts in Ottawa and has held the position of Curator of the House of Commons since 2014.