[January 18, 2023]

By Michel Hardy-Vallée

Fairy tales and novels of chivalry have the power to normalize royalty – a tenacious institution, despite revolutions and regicides. In photography, Ansel Adams is, in a way, royalty. One could even say that he “invented” normalcy, if we follow the terminology of his “zone system”: “normal” is a scene with a lighting contrast equivalent to five stops; “normal” is processing the negative so that it has the full range of grey tones while preserving the fine textures. In my own experience, what is more normal is a poorly lit scene in which one tries to photograph a moving subject, with film that one has not had the time to test and that will be developed by a bored lab worker.

Mike Mandel, Zone Eleven, Bologne, Damiani, 2021, 28 x 23 cm, hardcover, offset lithography, 112 p.

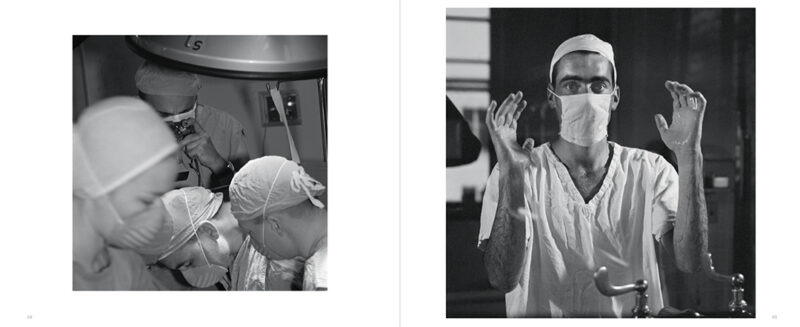

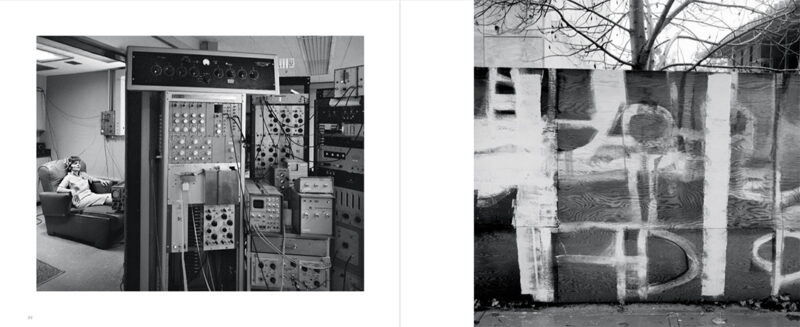

As a facetious postmodernist, Mike Mandel, like others, raises doubt about Adams’s norm, but he does so while acknowledging his own debt to and admiration for the figure whose work he reinterprets with this project of curating by book. The “zone eleven” in the title is not part of Adams’s system, which stops at zone ten, “paper white.” Mandel has blithely excavated the archives of Adams’s career in commercial work to weave together sequences that show the human, strange, even incongruous side of a photographer better known for his perfect landscapes. By dedicating his book to Larry Sultan, with whom he became known for Evidence (1977), Mandel here echoes their approach as surrealistic explorers of documents of the military-industrial complex.

There are many questions of authority (or, in this case, author-ness) inherent to Mandel’s project: how does one manage the profusion of images that the photographic medium makes possible; how does one keep major figures relevant as fashions change; who determines the meaning of an image; what distinguishes the collection of an original body of work? Mandel uses archives as an instrument, and we could consider him a curator or post-photographer, but I think that the concept of fan fiction better defines his approach and its limits. Penning a sequel to a successful novel by adopting the point of view of a secondary character or developing an episode that was only hinted at in the original story is to try, for a reader-author, to don the garments of a beloved writer. Despite some commercial success, the genre often suffers from the fact that it will be difficult to see it as anything but the inferior tangent of a dazzling work of fiction.

Still, Mandel’s selection scratches the surface of a pathos that he does not exploit beyond the intimation of a vague anxiety. It is mainly a jovial Ansel Adams that he features – rarely the one who photographed the internment camps for Japanese Americans during the Second World War; never the one who admitted profound hatred for his competitors of the 1930s, such as the very popular grotesque-style pictorialist William Mortensen. The photographic normalcy that Adams promoted, following in Alfred Stieglitz’s footsteps, was intended to be objective, founded on sensitometry rather than on the history of painting and printmaking. But the measurable parameters of this modern and scientific ideal are in fact based on statistical abstraction of the preferences of a population to whom different versions of a single photograph are presented.1 If there is one thing that the postmodernists have driven home, it is the constructedness of normalcy; Mandel draws limited lessons from this. Like Shrek, he makes fun of the importance accorded to Prince Charmings and royalty, but yet he does not establish democracy. Perhaps we will see other types of projects reinterpreting Adams’s archives when they enter the public domain.

The approach underlying Zone Eleven is the challenge that confronts heirs to family albums, art historians trying to highlight a body of work, and artists attempting a neoclassical approach: how to create with what already exists. This is also the central question for both art and photography critics. The posthumous “collaboration” “Mike Mandel x Ansel Adams” – names that are almost anagrams for each other – reveals a sincere admiration but, like a good slap on the back, it leaves few lasting marks. Translated by Käthe Roth

Michel Hardy-Vallée is a historian of photography and Visiting Scholar at the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, Concordia University. His research is concerned with photography books, visual narration, interdisciplinary practices, and the archive, in the contexts of Quebec and Canada. He has published his work in History of Photography and through a number of edited collections and conference papers. He is currently working on a monograph about John Max.