[Winter 2013]

par Gaëlle Morel

After devoting a number of projects to the world of work, Montreal photographer and videographer Emmanuelle Léonard investigates the notions of visual traces and information in her most recent works. Since 2007, Léonard has been making videos and photographic series1 on the themes of the police and the criminal investigation.2 In the project Homicide, détenu vs détenu, archives du Palais de justice de la ville de Québec (2010), Léonard appropriates a series of snapshots produced for and conserved in the legal system. This appropriation suggests an apparent retreat by the artist, but the creative exploitation of existing photographs in fact enables her to redefine the status of the images. Through the artist-archivist’s intervention,3 the probative nature attributed to the medium is challenged. Furthermore, Léonard brings forth prints that are usually ignored and viewing of which is reserved for a limited, specialized public. She thus examines legal confidentiality and the restricted access to these reclusive spaces responsible for conservation of images.

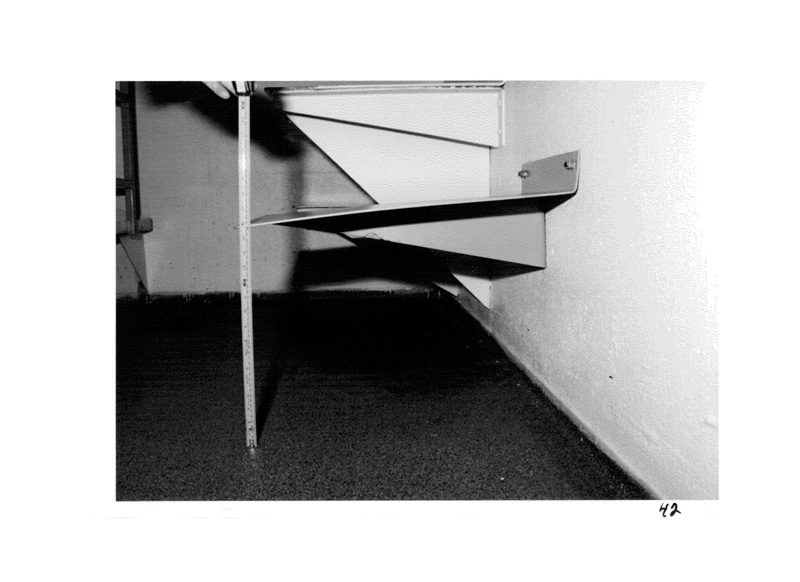

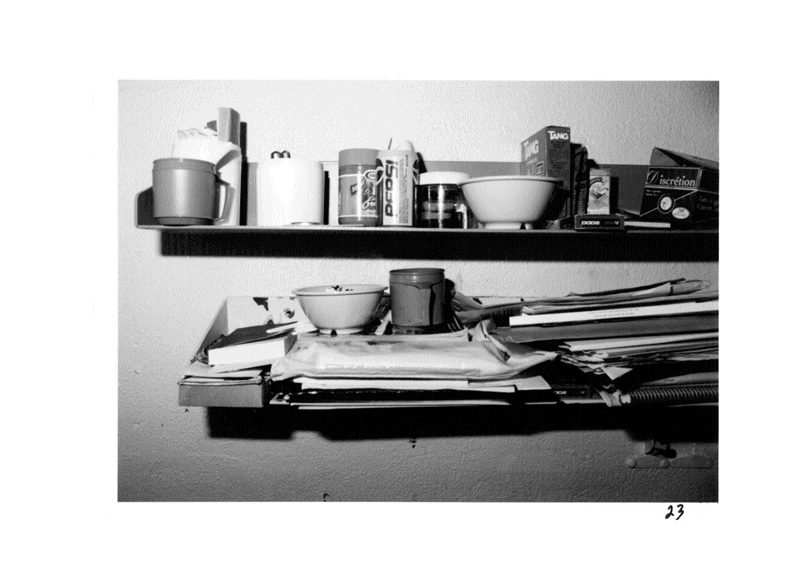

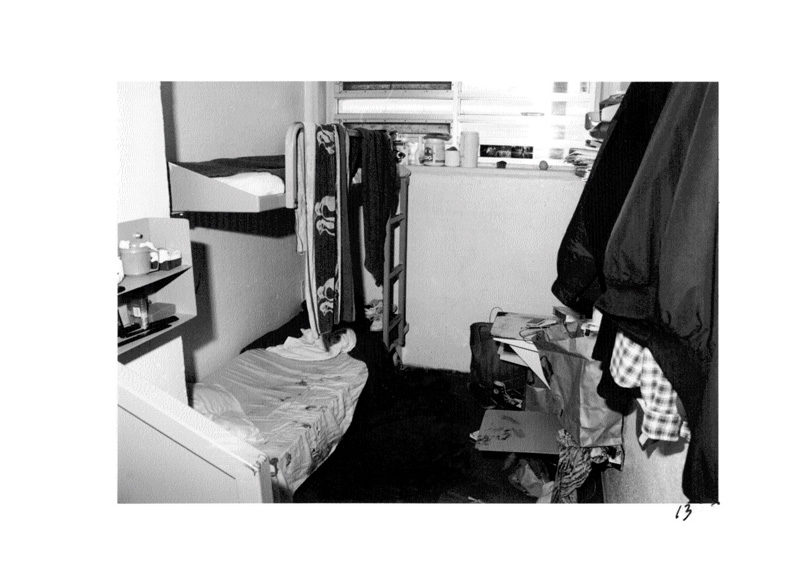

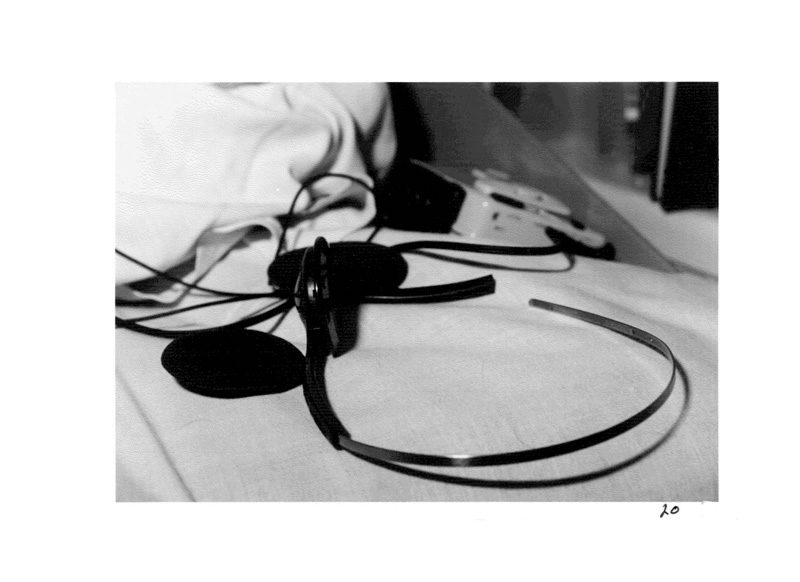

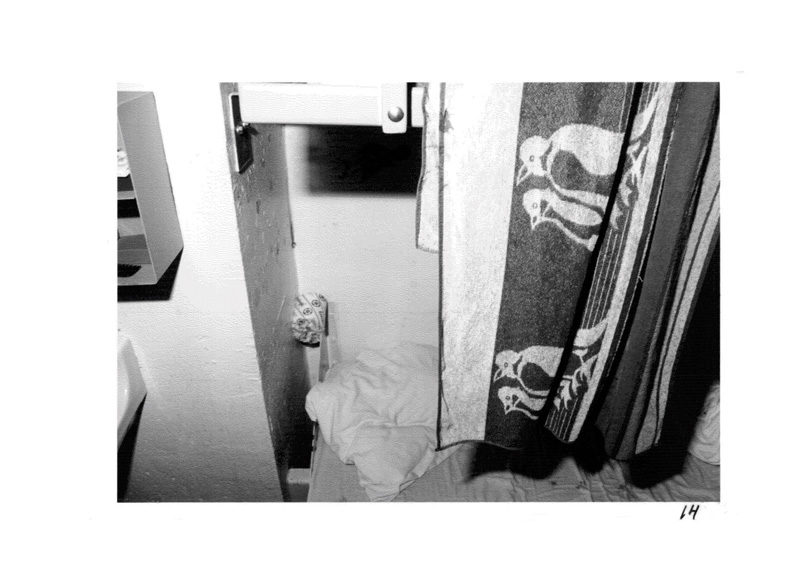

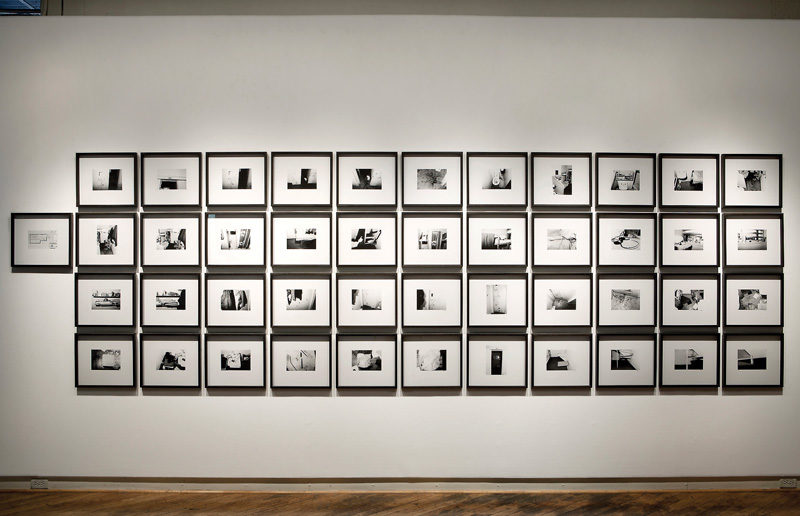

A New Functionality for Images. Homicide, détenu vs détenu is composed of a drawn plan (ill.) and forty-four black-and-white photographs in 33 x 37 cm format. The original colour pictures were taken in 1997 by a police officer as part of a criminal investigation following the murder of an inmate by his cellmate. Conserved in the archives of the Quebec City courthouse, the group of pictures includes a variety of points of view, from tight shots of specific objects (blank paper, pencil, earphones) (ill. 20) to general views showing how the room was organized (ill. 13). The rules used for taking the pictures correspond to visual codifications intended to determine the value of images in a legal context (ill. 42). The cramped space is systematically sectioned off and the photographs methodically inventory traces of blood on the floor and walls (ill. 4), a few pieces of clothing, the furniture, and dishes and notebooks arranged on shelves (ill. 23). The recording of evidence of the crime alternates with views revealing the two inmates’ daily life. Léonard concentrates on the representation of violence, real or symbolic, but refuses to take a dramatic or sensationalist approach. In particular, she highlights the paradox between the photographs’ apparent aesthetic neutrality and clinical aspect and the brutality of the deeds evoked.

Certain images include abstract, enigmatic shapes (ill. 44), implying a reflection on “the evidentiary value of the image.”4 The framing divides the space in an apparently haphazard and arbitrary way, cutting a portion of the door and window or showing only parts of the furnishings (ill. 14). Léonard ignores the informative nature and primary application of the images. She excludes from her project the manual of descriptive specifications that normally accompany the photographs, which serves as a reference and technical guide for police photographers so that their images meet the legal system’s precise requirements. In Homicide, détenu vs détenu, only the aspects of the context selected and supplied by the artist – the plan of the cell, the note of intention, the numbering of the images – allow us to comprehend and give meaning to the whole.

The “aestheticization of documentation”5 created by Leonard’s approach causes a shift in – even a profound modification of – the status of the archive. The manipulation and displacement of the photographs transform administrative documents into works accessible to the general public. The photographs of traces supposedly attesting to a tragedy are now assessed in the light of aesthetic criteria, altering their original value of registration and tracking. If appropriation of the corpus involves a form of withdrawal of the artist, this withdrawal is compensated for by the conceptual value of the project, the choice of subject in the archives, and the arrangement of the prints in the gallery space.

The Confidentiality of the Images. Having lost their customary value, these images produced in the legal context have fallen into the public domain and offer Léonard an opportunity to divert and challenge their original qualities. The status of “archive” is composed of an agency and a site of authority that the artist openly confronts. Ordered, institutionalized, and recorded, the documents used in Homicide, détenu vs détenu and conserved at the Quebec City courthouse meet certain standards and fit into a legal system. By modifying the original evidentiary and historical use of these archival photographs, and by highlighting their aesthetic qualities, Léonard casts a critical gaze at the site dedicated to conserving them. The site has a codified spatial organization and conventional layout that she reflects in her installation (ill., installation view of the exhibition at Gallery 44). The images are exhibited on the wall in a uniform, symmetrical grid, and the meticulous structure offers an equilibrium that underlines the ordered nature of the archive chosen. Nevertheless, through her intervention, the artist challenges the act of collecting, selecting, and excluding images, introducing disorder and disruption.

These sites, emblematic of political and administrative power, often restrict access. The artist reinvents her own role by presenting these normally invisible photographs in a different context. She seems to have what Jacques Derrida calls “archive fever,” a quest for the archive threatened with extinction.6 Exploring the legal issue of access to these images, Léonard offers a reinterpretation of these prints, usually reserved for expert eyes.

Often composed of images without a recognized “author,” the archive becomes a ductile, malleable creative material.7 With Homicide, détenu vs détenu, Léonard exhibits prints used for a specific crime investigation and forgotten once the case is tried and a verdict rendered. Collecting and recycling photographs found in the crime file, she suggests the possibility of an alternative expertise, casting an artist’s gaze on these documents and on the regulated aspect of the conservation sites. These images, appropriated, reinterpreted, and reproduced, open the path to an account presented by Léonard on different occasions. The artist’s story and her quest for archives mingle imagination and reality, giving rise to a form of performance that is renewed each time.8

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 See Gaëlle Morel, Emmanuelle Léonard: A Judicial Perspective (Toronto: Gallery 44, 2011).

3 See, notably, Hal Foster, “Archival Impulse,” October, no. 110 (Autumn 2004).

4 Nathalie de Blois, Emmanuelle Léonard: Un livre de photographies (Montreal: Occurrence, 2005), p. 34 (our translation).

5 Anne Bénichou, “Ces documents qui sont aussi des œuvres…” in Anne Bénichou (ed.), Ouvrir le document. Enjeux et pratiques de la documentation dans les arts visuels contemporains (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2010), p. 47 (our translation).

6 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

7 See Okwui Enwezor, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, exh. cat. (New York and Göttingen: icp-Steidl, 2008); Sven Spieker, The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy (Cambridge, ma: mit Press, 2008); Peggy Gale and Doina Popescu (eds.), Archival Dialogues: Reading the Black Star Collection, exh. cat. (Toronto: Ryerson Image Centre, 2012).

8 See, for example, vimeo.com/30200316.

Emmanuelle Léonard lives and works in Montreal. Using photography, video, film, animation, and newsprint, she brings out strong social, cultural, and political significances. She explores the conventions of documentary, press, and medico-legal photography and of video surveillance. Léonard has a bfa from Concordia University and a master’s degree in visual and media arts from uqam. Her work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions in Montreal, Toronto, Quebec City, Berlin, and Paris, and in 2011 she participated in the Triennale québécoise at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. In 2012, a selection of her works was on display for the Grange Prize exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. emmanuelleleonard.org

Gaëlle Morel is exhibitions curator at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto. She has a Ph.D. in history of contemporary art, is a member of the editorial committee of the bilingual magazine Études photographiques, and was guest curator of Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal in 2009.