[Summer 2019]

By Claudia Polledri

Context. The 22nd edition of the Paris Photo international photography fair took place November 8–11, 2018, in Paris. During the four-day fair, crowds of artists, gallery owners, collectors, publishers, curators, journalists, and photography lovers bustled through the Grand Palais, which had become a labyrinth of images organized by Paris Photo director Florence Bourgeois and artistic director Christoph Wiesner. What took place in the light flooding through the magnificent glass roof of the exhibition hall, a setting worthy of the grandeur of the event, was a crossroads of images and encounters. In this showcase that aimed to bring creative people into contact with art dealers, the public, it must be said, drew almost as much attention as the photographs. A microcosm that was ephemeral yet concrete, Paris Photo’s content was remarkable in both quantity and quality, even though the event was circumscribed by the exclusivity of access criteria for exhibitors. A few figures: 199 exhibitors from 38 countries organized into five “sectors” (Main, Prismes, Book, Curiosa, and Films). The exhibitors comprised publishers, offering a goldmine for photobook lovers1; artist films chosen from among projects submitted by exhibitors; and galleries (a total of 168 between the Main and Prismes sectors), the real flesh and blood of the fair. Although much more numerous than last year, galleries from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and South America were still in the minority, as most exhibitors came from Europe and North America2. The newly inaugurated Curiosa sector was organized by curator and art critic Martha Kirszenbaum3. She chose to present a selection of erotic images “that redefine our gaze at the fantasized and fetishized body, tackling the relations of domination and power, as well as questions of gender.” Perhaps Paris Photo had to reach past the age of majority to dare to undertake such an initiative. In any case, once one crossed the threshold of the Grand Palais, there was only one question to ask: Where do we start?

“Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers”? Traditionally devoted to “exceptional projects,” this year the Prismes sector hosted fourteen galleries in the raised space of the Salon d’honneur, which gave the images – and those looking at them – more room to breathe. Nevertheless, it was difficult not to hold one’s breath when looking at the anthology of ancestral and neo-primitive photographs by Isabel Muñoz organized by François Cheval and Audrey Hoareau with Galerie Esther Woerdehoff (Paris), for the project Anthropologie des sentiments.4 Apprehended, at first glance, as an investigation of rituals to which the body is subjected in different cultures, these pictures form a journey on their own. From the hypnotic dances of Turkish whirling dervishes, to tattooed bodies suspended in the air by hooks piercing their skin, to faces from the Chinese community of Thailand pierced with spikes, the body is here but a threshold opening to another dimension. These powerful images, the expressive force of which is underlined by the choice of large format, give a glimpse of the universality of all languages related to a form of belief, a religion, or mythologies.

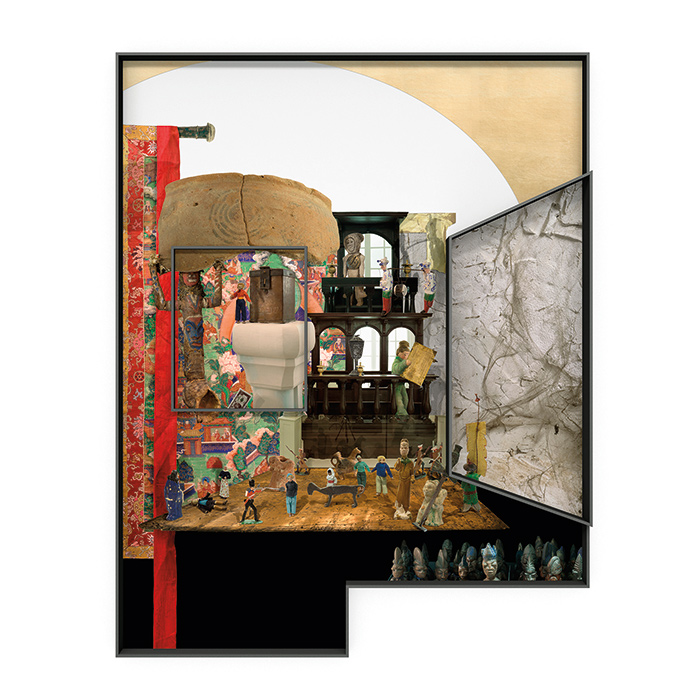

It is not essentiality but saturation that characterizes the large photographic panels by Israeli photographer Ilit Azoulay (Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv) from the series No, Thing dies (2014–17). In these unusual collages, a reinterpretation of the cabinet of curiosities, Azoulay combines in a single frame images of objects and representations of spaces in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, retracing its history since its foundation in 1965. One doesn’t have to dig to see in these works the reference to historical temporalities and, especially, to the notion of “collection” embodied by the accumulation of objects as witnesses to different eras. But it is the visual dimension of these panels that is particularly original. Once captured, the gaze is then dispersed among figurines, mosaics, tapestries, open drawers, shelves and filing cabinets, icons, pieces of bricks, and many other things. These are image-maquettes, in short, that materialize strata of memory and call upon the infinite interplay of decoding.

These remarkable photographs introduce a new initiative by Paris Photo that is worthy of mention: the exhibition Elles × Paris Photo, produced in collaboration with the French Ministère de la Culture and organized by independent curator Fannie Escoulen. Composed of a hundred images, this visual abecedarian5 highlights the contribution of women to the field of photography. In this sense, it is related to the recent exhibition Qui a peur des femmes photographes ? 1839–1945,6 which it expands to the contemporary era. Starting with the “angelic” Circe by Julia Margaret Cameron (1865), a Victorian-era pictorialist photographer and the first woman admitted to the Royal Photographic Society, the itinerary unfolds throughout the twentieth century and finishes with the “non-portraits” by Spanish photographer Andrea Torres Balaguer (Galerie In Camera, Paris). Part of the series The Unknown (2018), each of these muted images shows a female silhouette (the artist’s), the face hidden behind a stroke of paint. Although they erase the model’s identity, these fine layers of gold, silver, and bronze enhance the pictoriality of the composition already visible in her posture and the associations of images, and they propose a careful rereading of the photographic genre of the self-portrait. In the 1920s, women photographers used this genre to play with gender codes and show its possibilities for introspection, “identity and sexual challenges,”7 and provocation. Although the intention of this exhibition is not to write a history of women’s photography, its source nonetheless arises from a historiographic observation concerning the “lack of representation and visibility” of women’s contribution to photography. Elles × Paris Photo thus bears both a pedagogical and an artistic vocation in relation to the public, collectors, and publishers. Furthermore, the choice not to exhibit these images on their own but to indicate them by a legend in the respective galleries in which they appeared seems to confirm this. Apart from some twenty photographs going back to the modernist avant-gardes of the 1920s and 1930s (such as those, using the iconography of broken dolls “symbolic of the social reproduction of female roles,” by Ruth Bernhard [Doll’s Head, San Francisco, 1936] and Anna Barna [Doll II, 1930]) most of the images in this exhibition were produced between the 1940s and the present. Among the contributions by feminist artists of the 1960s and 1970s are Janine Niépce’s accounts of political battles (Grève des femmes pour l’égalité salariale, 1966),8 Penny Slinger’s provocative image Bride’s Prayer (1973),9 and Renate Bertlmann’s Douce Danse (1976).10 Notable is the solo show by American photographer Joan Lyons (b. 1937) presented by the Steven Kasher Gallery (New York), which includes the standout large-scale serigraphy on fabric, Bedspread (1969), an ethereal piece that repeats a full-length nude image of Lyons on a silk sheet.

The theme of violence against women, very much in evidence, was focused around images of the body. Whether referring to the colonization era, as in Fatima Mazmouz’s mosaic series of images Bouzbir (2018),11 named after a Casablanca district reserved for the French army in the 1920s that became synonymous with prostitution, or to the contemporary era with Viktoria Binschtok’s engagement with the “#metoo” movement12 (#metoo & bloody hands series, 2018), photography continues to act as an instrument of denunciation, identity affirmation, and deconstruction of preconceived ideas. Lydia Flem’s magnificent and terrifying photograph Artemisia (2017), part of the Féminicide series,13 is highly meaningful in this regard. Flem explains, “I claim this banality of the form because it resonates with the background banality: this ancient mixture of exaltation of female beauty and of violence that is constantly perpetrated on women because they are women.”14 Unlike the other pictures in the series, the reference to Caravaggian painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654)15 evokes something more: the opportunity that painting and photography have afforded women to leave the frame and challenge their own identity via the image.

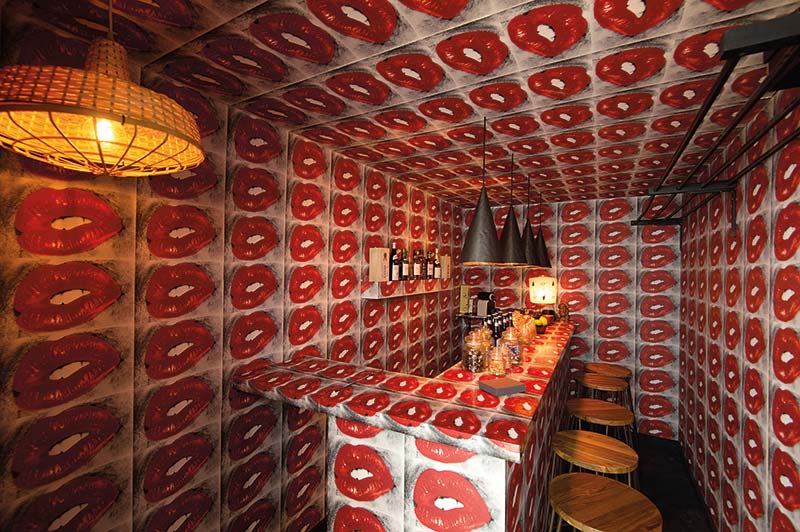

Japanographies. Red lips: this is what links – or perhaps doesn’t link – the path from Escoulen to Daido Moriyama. Once again in the Prismes sector, we find the installation Lip Bar (with counter, stools, and Asahi beer) presented by the Hamiltons Gallery (London).16 It is a reproduction of Moriyama’s Lip Bar, which, in 2005, covered the Kuro Bar, a small popular bar in Shinjuku, west of Tokyo, with repetitions of the same image: a close-up of half-open red lips. A recurrent subject for Moriyama, often seen in his photographic wanderings in the neighbourhoods of Tokyo, in this installation the image forms a mosaic and, via the architectural statement, acquires an immersive dimension that envelops the gaze.

This year, after the exhibition Another Language presented by Simon Baker at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2015, Japan was once again a significant presence at Paris Photo (in quantitative proportion) and even more at Fotofever at the Carrousel du Louvre, a parallel event organized by Yuki Baumgarten and targeting emerging photography. At the Grand Palais, aside from Moriyama, a pillar of the Japanese photography scene who had a selection of pictures from the hypnotic series Tights and Lips presented by the Akio Nagasawa Gallery, images by other icons, such as Kenji Ishiguro (Heartless Room) and Nobuyoshi Araki (Bondage series, 1997), were also shown. Ishiguro’s erotic photographs of bound women, their bodies caressed by the silk of multicoloured kimonos, found their niche in the Curiosa sector.17 Also in black and white, the Japan of the 1970s and 1980s returned in the photographs by Issei Suda18 (Childhood Days) devoted to the “children of the Sho-wa era.”19 Like the pictures in Fushikaden, Suda’s first book (1978), this series shows “elements of childhood preserved from the flight of time”:20 with all the nostalgia and emotion evoked by awareness of the irreversibility of time, that happy period of childhood is conserved in a “jewel box” and the historical era that framed it. With Diane Dufour’s talk (Le Bal) on “the exhibition as a means of expression,”21 we returned to the time of the renowned Japanese magazine Provoke, founded in 1968 and known for the photographic style that it helped to spread through Japan: “rough, blurred, and out of focus.”22 A student of this style, and of Shomei Tomatsu, photographer of the wounded postwar national identity, Mao Ishikawa (Nap Gallery, Tokyo) chose to document the community of black American soldiers on the island of Okinawa when it was occupied (1945–52) and who remained under the American administration until 1972. Ishikawa’s photographs document her exchanges with this community of soldiers between 1975 and 1977, love between them and Japanese women, and their free and uncomplicated way of life, but she also addresses the themes of the particular identity of the island, belonging to a group, relations among communities, and the American military presence, a question that remains current. In her photobook Red Flower,23 Ishikawa chose to enclose these black-and-white images in a red cover: “red like akabana flowers”, she says, and like the “gaudy, free, and strong” women of Okinawa. Not quite the same tone as the red of Lip Bar.

From Japanese photography to printing on Japanese paper, another recurrent element in the stalls of Paris Photo. A sophisticated technique that is increasingly popular among photographers, it produces the paradoxical effect of coating the image through its support, although this does not always guarantee the quality of the photograph. From Lisa Sartorio’s rather banal pictures (Ici ou ailleurs, 2018, Galerie Binome, Paris) in which the vulnerability of the Japanese paper is used for visual representation of conflict, we move to the evocative photographs by Aline Diépois and Thomas Gizolme in their series White Isles of the South Sea (2015) presented by Galerie VU’.24 Assembled alternately in black and white and in colour, these delicate and disturbing Polaroids document the subsidence of the Kiribati Islands, a small archipelago in the Pacific that will cease to exist due to global warming. Rather than a detailed view of the landscape, Diépos and Gizome seek the state of mind provoked by this disappearance, both tacit and tangible in the images. It is aptly summed up in a picture of child’s hands barely emerging from the water, and in the dark, melancholic shot of two byways sharing the frame: the left-hand one is the ocean; the right-hand one is a road on which a truck rolls away from the lens, setting off for a new destination. That is also the only possible end for the residents of these islands destined to disappear within twenty years.

Finally, in the series The Mouth of Krishna by the Spanish duo Alban Cabrera and Angel Albarrán (Galerie Esther Woerdehoff, Paris), we find not only prints on Japanese paper, sometimes enhanced by gold leaf, but also the quintessence of a “Japanizing” aesthetic that gives rise to light, refined images in which the framing creates a dialogue between forms found in nature and the regularity of geometric figures – almost photographic haikus.

“Dare alla luce” (Bringing to the Light). Dare alla luce means “bringing to the light” but also “giving birth.” Thus, the title of the work by Canadian photographer Amy Friend (2016, Galerie In Camera, Paris), presenting old photographs pierced and penetrated by light, referred to the sources of photography – writing with light. Just as luminous, the photographs from the series Les Portes de glace by the talented Juliette Agnel25 (Galerie Françoise Paviot, Paris) also evoked a return to origins, though interbred with current technology. Agnel developed an audacious process that combines camera obscura technique with digital technology, enabling her to transform images directly into the shot. On the aesthetic level, her photographs marry the primitive character of the pinhole camera with the reconstruction produced by digital sensors. Between icebergs and starry skies, Agnel’s photographs refer to the Kantian sublime and to the infinite expanse of the landscape by which she says she is “inhabited.” Just as experimental and primitive, Jonas Delhaye’s photographs (Galerie Maubert, Paris) involved the construction of pinhole cameras in widely disparate contexts and places. For example, around a tree (Liquidambar, 2014), he constructed a photographic shelter so that the light would be imprinted on sheets of photosensitive paper placed in a circle around the trunk, and he used the light passing through a keyhole (Étant donné, 2017) to gather images that are displayed on photosensitive surfaces placed on the wall of a darkened corridor. At once image, trace, device, and creative gesture, Delhaye’s photographic work refers us to the essential nature of photographic genius and projects its infinite potential.

By the end of the fourth day, walking around Paris Photo became almost a memory game. One could turn around to other sights, some seen previously (Robert Frank, Dorothea Lange, Richard Avedon, Berenice Abbot) and others more recent and just as exciting, such as Silvana Reggiardo’s plays on light and reflections26 (Effet de seuil, 2013–15), the incredible multicoloured photographic sculptures reinterpreting the Balogun market in Nigeria by Lorenzo 27 Vitturi (Money must be made, 2017), Iranian photographer Newsha Tavakolian’s poignant photojournalism (Agence Magnum), the luminous landscapes by Stéphane Lavoué,28 Payram’s adventure on the Silk Road Sur les traces de Paul Nadar,29 and the urban geometries of the young Moroccan photographer Hicham Gardaf,30 with the blue sky seeping between orange walls (The Red Square, 2016). But this will be for another time.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Specifically, the main sector hosted eight galleries from Asia, four from the Middle East, four from Africa, and three from South America. The 2018 edition of Paris Photo included forty-two new galleries, twenty-two of them new participants.

3 Kirszenbaum was also curator of the French pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale.

4 Anthropologie des sentiments gave rise to an exhibition and a photobook co-published by François Cheval and Audrey Hoareau (The Red Eye) and the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte(2018).

5 At least this is how this itinerary is presented in the small catalogue produced for the occasion and distributed free of charge. It must be noted that this event was accompanied by a series of talks, also organized by Fannie Escoulen, about gender stereotypes and the visibility of women’s photography in museums and collections. Encounters with the artists were also offered, including with Tahmineh Monzavi (Iran), Fatima Mazmouz (Morocco), and Joan Lyons (United States).

6 The exhibition was organized in 2015 by curators Ulrich Pohlmann, Thomas Galifot, and Marie Robert and was presented at the Musée de l’Orangerie (part 1, 1839–1919) and the Musée d’Orsay (part 2, 1919–1945). The catalogue was co-published by Éditions du musée de l’Orangerie/musée d’Orsay and Éditions Hazan.

7 Thomas Galifot,Qui a peur des femmes photographes ? 1839-1945 (Paris and Vanve: Musée d’Orsay and Éditions Hazan, 2015), 34.

8 Polka Gallery, Paris.

9 Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.

10 Steinek Gallery, Vienna.

11 Galerie 127, Marrakesh.

12 Klemm’s Gallery, Berlin.

13 Galerie Françoise Paviot, Paris.

14 Lydia Flem, “15 photographies extraites de la série Féminicide,” Muse Medusa magazine, http://musemedusa.com/dossier_6/flem/ (our translation).

15 A paradigmatic figure for her struggle for recognition of the violence she suffered at the hand of her drawing master, Agostino Tassi, Gentileschi took him to court (1612), which would result in further violence. Nevertheless, she succeeded in returning to her vocation, and in 1616 she joined the Accademia delle Arti e del disegno in Florence.

16 Cost of the installation €66,000. It includes plans, authorization to reconstruct the bar, and the wallpaper of lip serigraphies reproduced by Moriyama.

17 Both artists were present for an encounter with the public as part of the extensive program of talks organized during the four days of the fair.

18 Galerie Jean-Kenta Gauthier, Paris.

19 This refers to the period between 1929 and 1989, called the “period of enlightened peace,” under the reign of Emperor Sho-wa.

20 Kaneko Ryûichi (ed.), Les livres photographiques japonais des années 1960 et 1970 (Paris: Seuil, 2009),212 (our translation).

21 This talk was part of an extensive program organized for Paris Photo. Other speakers were Olivier Lugon (Université de Lausanne) and Roxana Marcoci (photography curator, MoMA). In this regard, we must remember the exhibition that took place at Le Bal in Paris in 2016 devoted to the renowned Japanese magazine: Provoke, entre contestation et performance. La photographie au Japon 1960-1975.

22 This slogan, “Are-Bure-Boke,” was also used for the title of the exhibition Rough, Blurred and Out of Focus: Provoke Magazine and Japanese Post-War Photography, held at the The Art Institute of Chicago in 2012.

23 Mao Ishikawa, Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa (New York: Session Press, 2017).

24 Thisphotographicseriesisaccompanied by a short film of the same name.

25 Agnel was a finalist for the Prix découverte at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2017.

26 Galerie Mélanie Rio Fluency, Nantes.

27 Galerie Flowers, London.

28 Galerie Fisheye, Paris.

29 Galerie Maubert, Paris.

30 Galerie 127, Marrakesh.

A post-doctoral student and lecturer in the department of art history and film studies at the Université de Montréal, Claudia Polledri is also the academic coordinator of the Centre de recherches intermédiales sur les arts, les lettres et les techniques at the Université de Montréal. She holds a PhD in comparative literature from the Université de Montréal; her dissertation was on photographic representations of Beirut (1982–2011) and the relationship between photography and history.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 112 – COLLECTIONS REVISITED ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Paris Photo, A Game of Memory — Claudia Polledri ]