[November 2, 2022]

By Luce Lebart

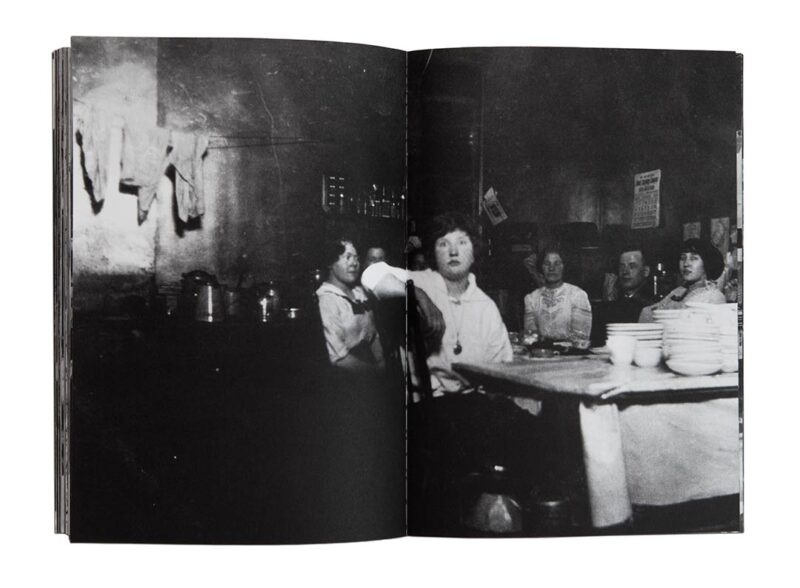

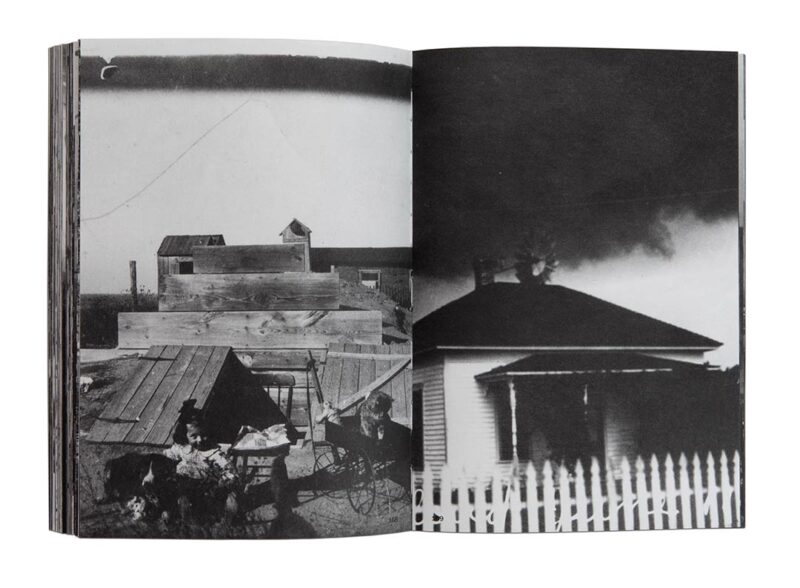

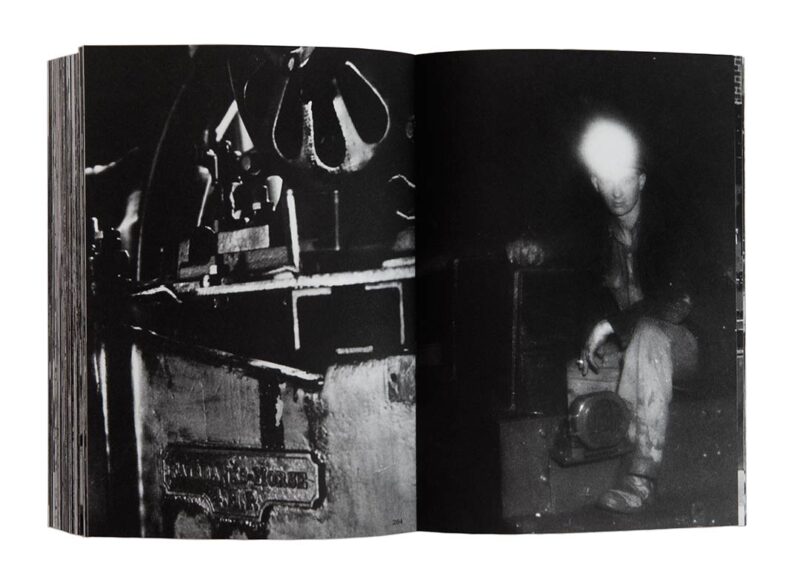

Dry Hole is the new opus of archival photographs published by British Morel and AMC. The 464 pages of images with deep blacks and illuminated whites lead readers into the meanders of daily life in the countryside and small towns of North America in the early twentieth century.

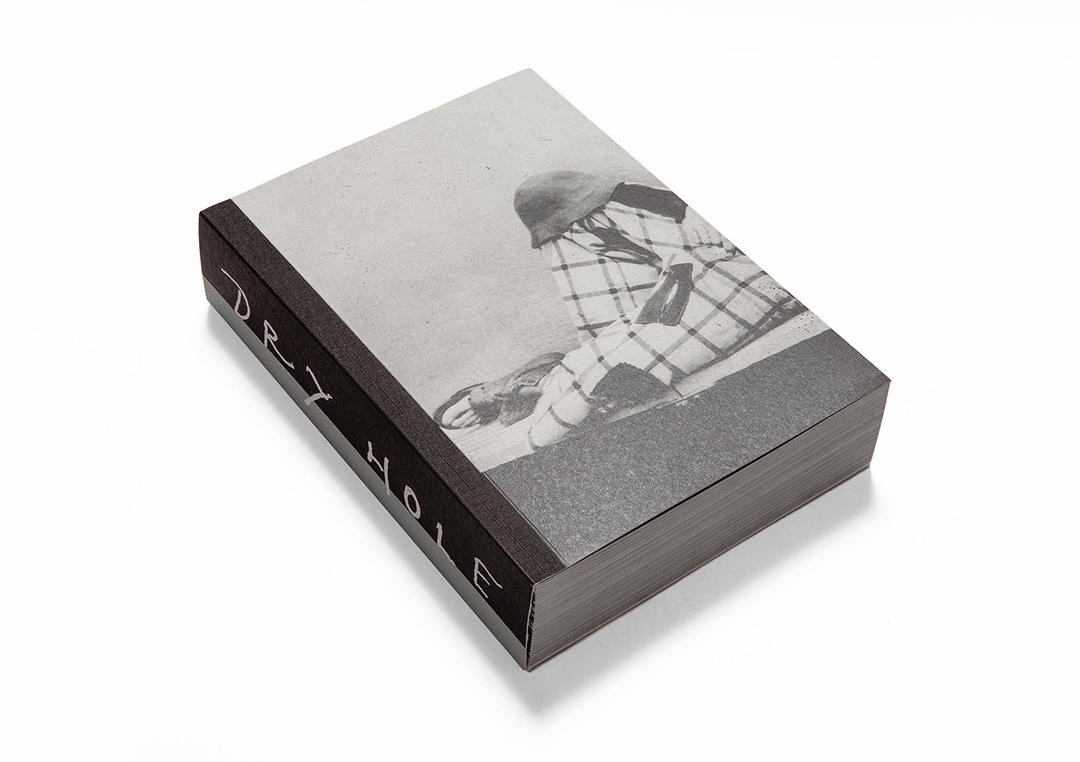

David Thomson, Dry Hole, London: Morel Books et AMC Books, 2022, 24 x 17 cm, paperback, 464 p.

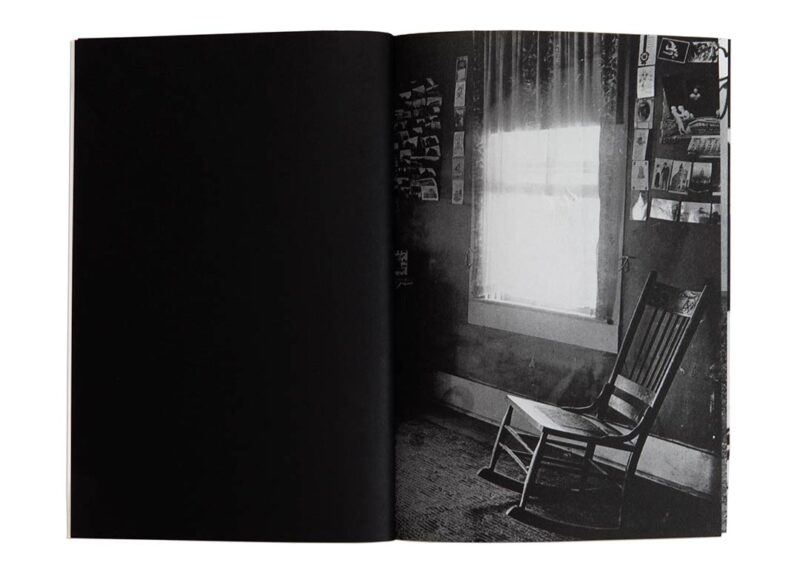

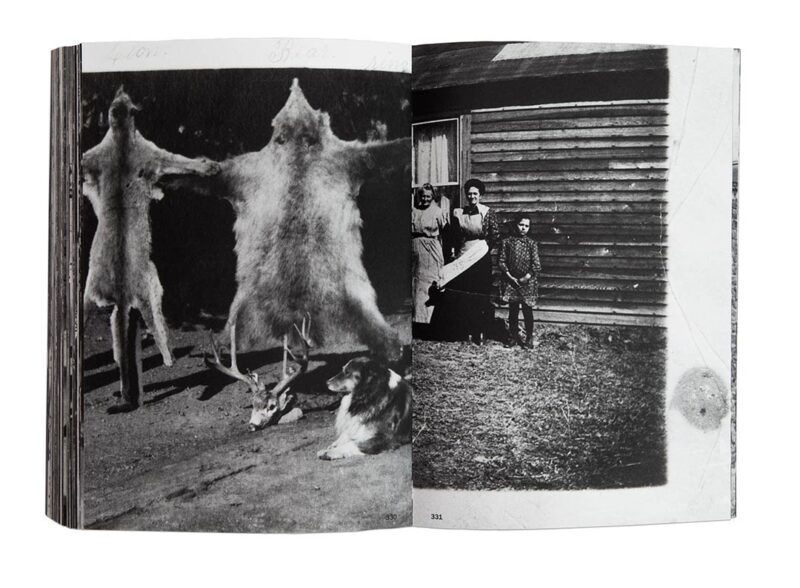

We dive into this book as into a bottomless chasm. Objects take shape and impressions surge – memories, smells, sounds, and more. The pages crash against each other. They bring together fragments of photographs captured here and there. These fragments cohabit. They talk to each other. They repel and attract each other, interrupt and extend each other. More rarely, a single image suddenly takes over a double page.

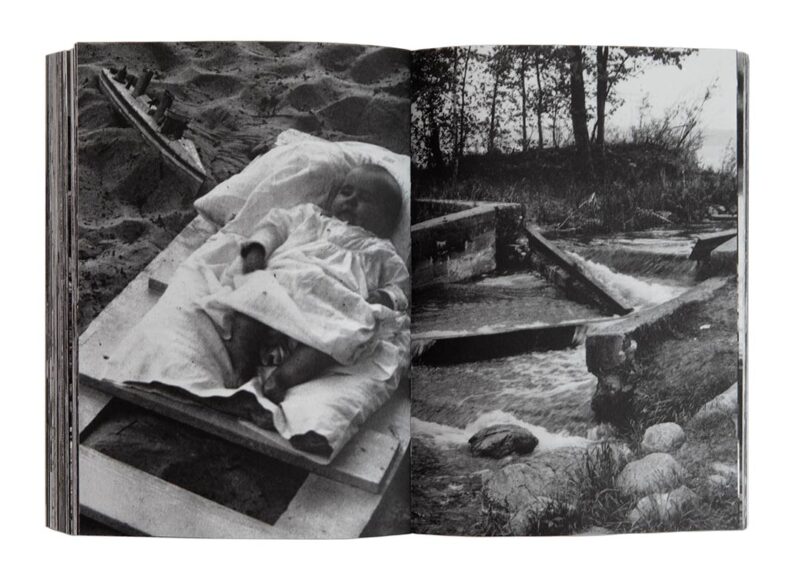

Here, a white-clad infant is stretched out on an improvised raft, on the sand. There, a collapsed dam lets turbulent water gush through, while a small wooden boat is beached beside the child with closed eyes.

Farther on, a hat sits on a bent leg. Under the hat, and standing in for a head, is a knee. The cotton pants that cover the leg are bedecked in patches, and the shoe is gaping with holes from wear and labour. Beside this image is a close-up on a dark, amorphous mass that we understand is emerging from a plate; it is none other than a loaf of bread. A mountain of food in a rough, austere world. These enigmatic shots are the front and back covers of the book and set its tone.

Dry Hole is built from vintage photographs gathered by Canadian collector David Thomson from the Internet during the pandemic, in 2020 and 2021. These vintage photographs are hybrid images, halfway between postcard and analogue photograph. They are “real photo postcards,” (RPPC), photographs taken to be sent by mail, as correspondence. People would share pictures of themselves or their homes, send them to those they loved and missed.

The making of real photo postcards was widespread in the early decades of the twentieth century, particularly in North America. The practice was encouraged by a flourishing photography industry, especially Kodak, which sold prepared paper and cameras facilitating the production of negatives in this new format. The postcard format was directly inspired by its predecessor, the album card, which was very popular in the late nineteenth century, both for tourist views of landscapes and for studio portraits. An album card consisted of developed printing-out paper glued onto a rigid card support. The gluing method was originally dictated by the technical constraints of albumen paper, which was very thin and rolled on itself if it wasn’t mounted on a stiff support. This type of mounting continued even when baryta paper, which was thicker and didn’t need mounting, began to be used.

The album card thus metamorphosed into the photographic postcard. The images, however, were no longer tied to their original purpose: in the former case, it was about collecting them in albums, and thus gathering them for oneself; in the latter, they were designed to be mailed and therefore dispersed far from oneself.

Most images on photographic postcards were taken by village or travelling photographers or by amateurs. They recorded everyday life from the point of view of those who were living it. Sometimes, spectacular shots of catastrophes, fires, or tornados were marketed. In any case, most of the time they were unique images, far from the multiple principle of common postcards.

The hundreds of images gathered here have become clay moulded by the book’s author. His trenchant gaze cuts and overlaps, frames and dissects. He scrutinizes and enhances details. He is drawn to the light, the spot of white that becomes more and more blinding. The gaze touches the paper and is thrown into the pit, the void, oblivion, and that which no longer exists: Dry Hole.

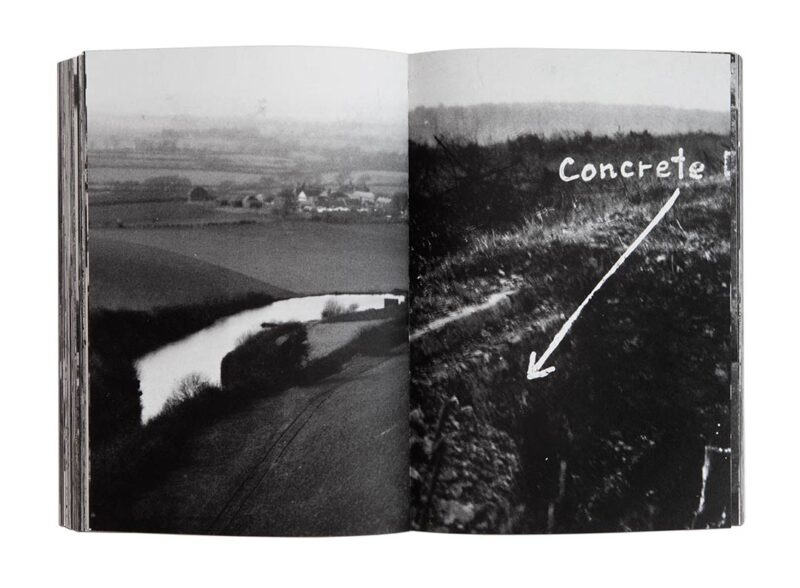

The title of the book itself comes from a detail in one image. It evokes the vain effort and adversity of hostile or hopeless situations, that of a well that runs dry or of arid land. The term figured originally in a banner brandished by a man posed on the front steps of a wooden building. Its handwritten appearance, displayed in white in white on the book’s thick spine, reminds us of the link maintained by the book as a whole with the written and with words.

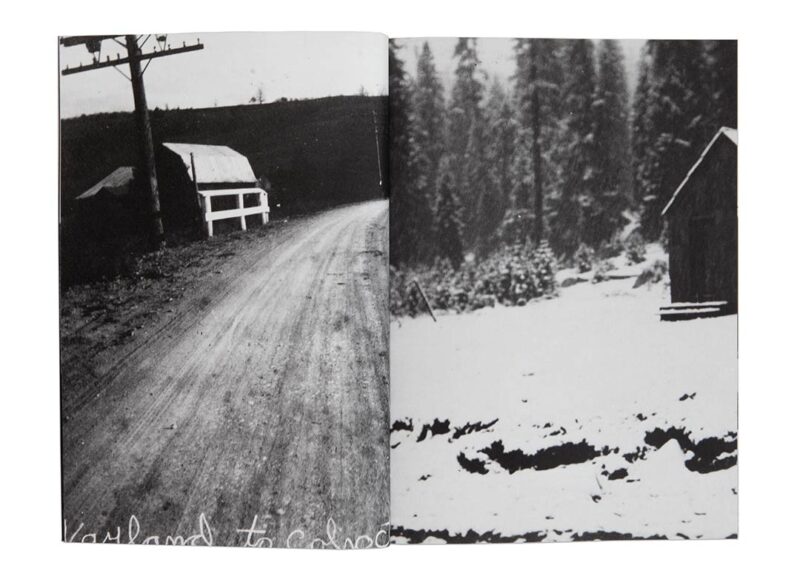

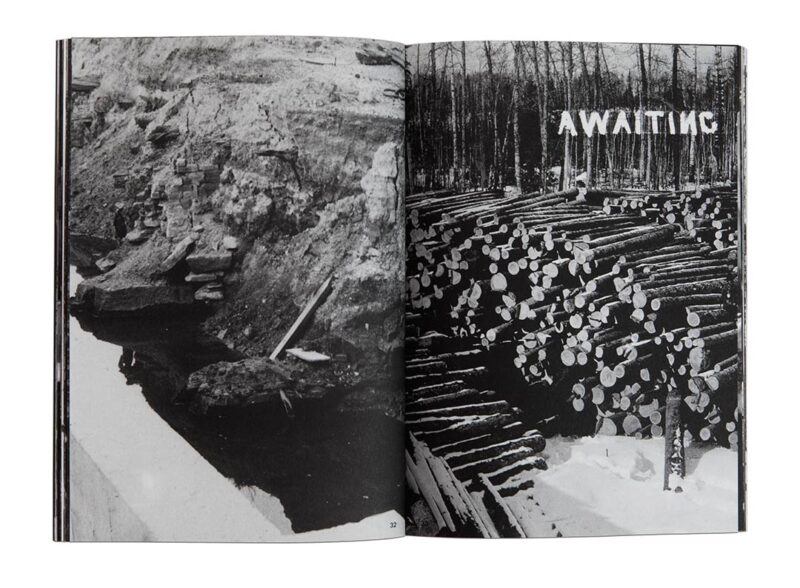

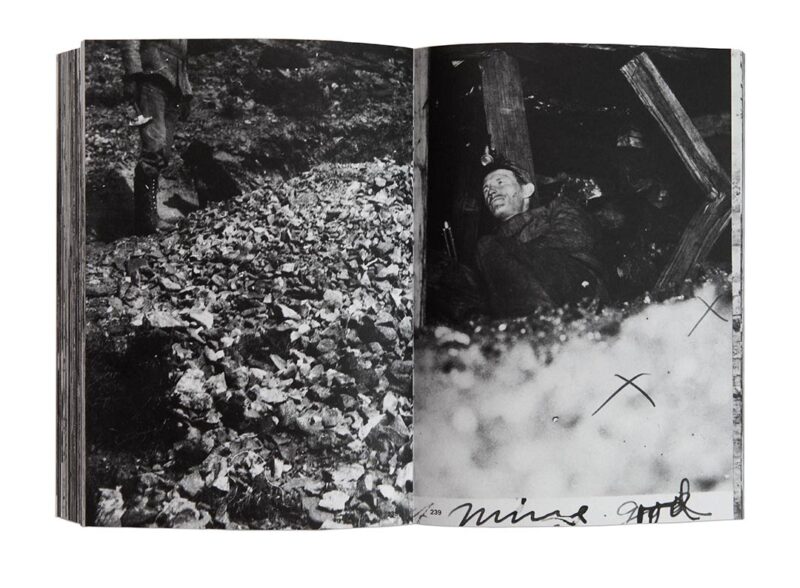

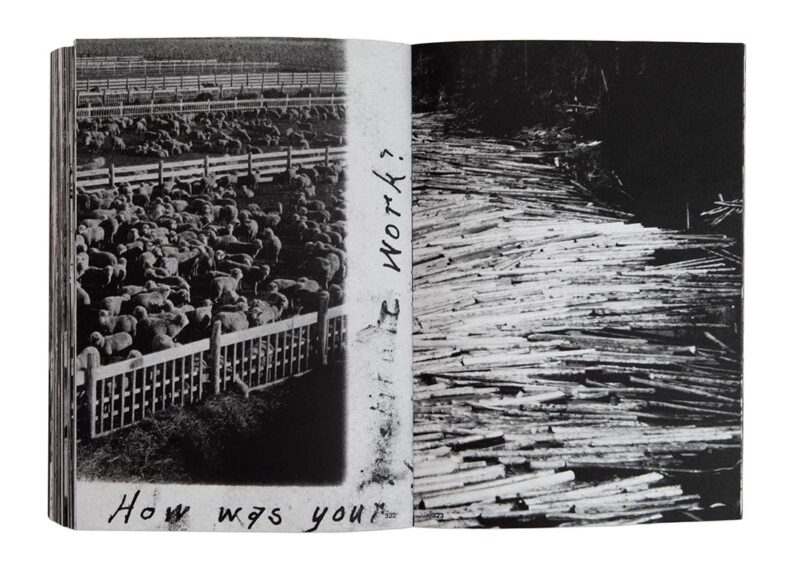

Words punctuate the book and are found both in the images (foodstuffs labels, a slogan on a fence, words on the gate to a warehouse); on the images (a legend or a comment that was previously appended or added to the black varnish on the negative – the words then appear in white, or in black on the positive); finally, behind the images, on their backs. The handwritten undersides punctuate the sequence of images. These white pages have black writing that is sometimes vertical, sometimes reversed, reframed, and enlarged; they create breathing spaces.

The handwritten words record hesitations and the tension in the hand, more accustomed to working the land and handling saws and shovels than holding to a pen. The zooming in heightens the sense of fragility and intimacy. What the words say is both banal and moving: “I probably won’t be home till Saturday night. But I might,” a father takes care to write to his daughters – short sentences that bespeak the hope of seeing them soon. The associations of images sometimes create unexpected successions of meaning and non-meaning, as if in a game of exquisite corpse. It is similar for the encounter between “Miss” and “Don’t come on Sunday,” between “Waiting,” “Morning,” and “Sacred Music,” between “Keep out” and “At home,” and so on. Often, the words are isolated, intensifying their impact. The word “mine,” which seems to be scratched into the gelatin of one of the photographs, says much about connection with the earth – working with it and the desire to appropriate it, to take root in it – in short, to settle on it.

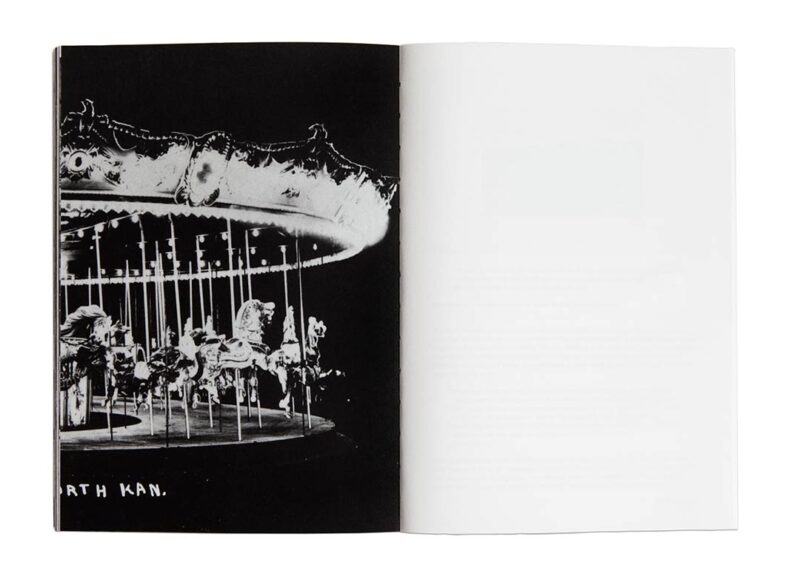

In addition to words, the images themselves are sometimes meta-images. For instance, the book opens on a photograph of a rocking chair in a wooden cottage whose walls are covered with an avalanche of photographs, a discreet preview of where Dry Hole takes us, page by page, on the way to the final picture: a 1900 carrousel of wooden horses that turns and turns endlessly to an endless tune; in its wake, ceaselessly, flow all the fragments of images and visual impressions. Translated by Käthe Roth

Luce Lebart is a photography historian, curator, and writer