By Zoë Tousignant

I travelled to Quebec City to see Serge Clément’s exhibition Constellations on a snowy Sunday afternoon in April. I had little prior knowledge of the show, presented at VU, centre de diffusion et de production de la photographie from March 21 to April 20, 2014, save for its basic idea: to showcase Clément’s collection of photobooks. Upon entering the artist-run centre’s main gallery, I quickly realized that something unusual had been mounted – that the exhibition provided an unexpected and potentially illuminating experience of the photobook.

Four display cases featuring some fifty books were positioned at regular intervals around the room. As the gallery assistant graciously informed me, each of these display cases was thematically divided in two. The first included a group of photobooks that had a crucial impact on Clément in the early stages of his career, and another group that influenced its development. The second case presented books that address the notion of fiction and its place within reality, and others that make use of the vernacular photograph as material and inspiration. The third brought together publications on the ideas of cultural identity and self-representation, and the last combined books addressing the theme of nature and agriculture with others having to do, in one way or another, with pigs.

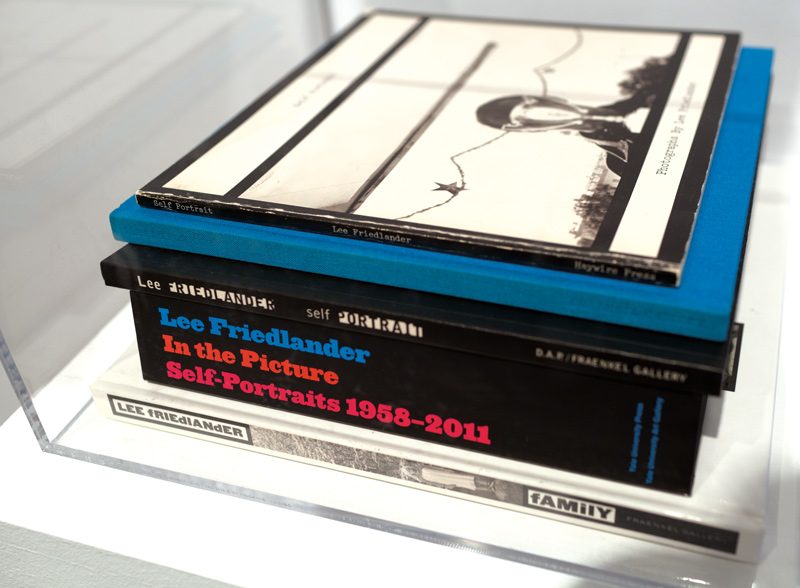

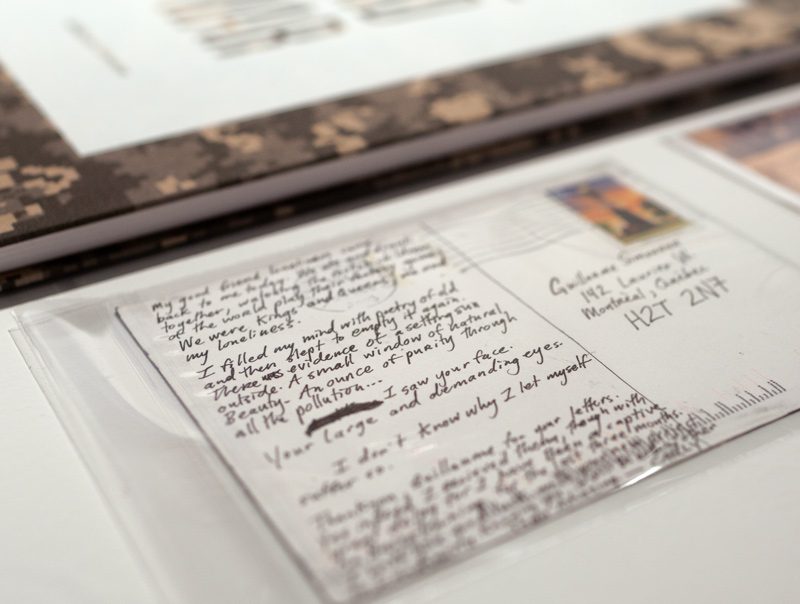

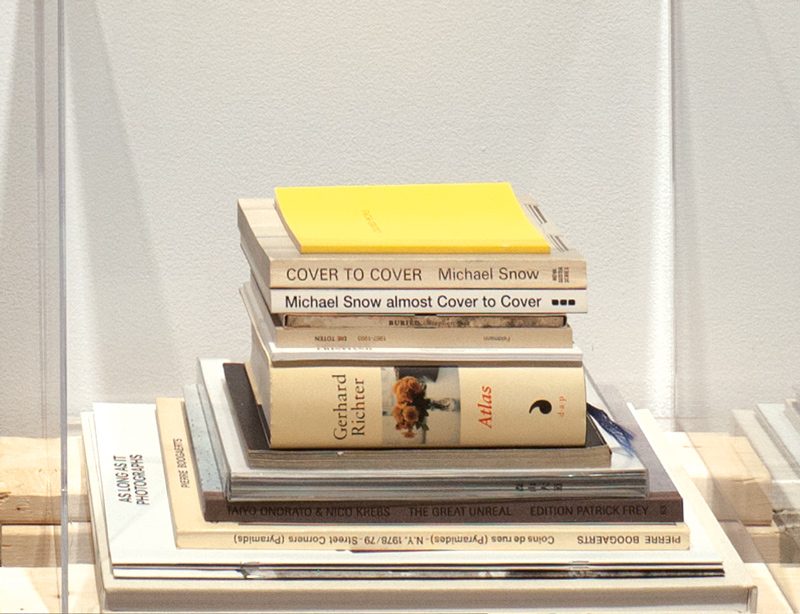

Although the majority of the photobooks were displayed closed, a “constellation” of thirty-four photographs hung on the gallery wall reproduced double-page spreads from a selection of the books under glass. Joining these two central components of the exhibition were items disposed disparately around the room – for example, a 1972 photograph from John Max’s Open Passport series hung beside a pamphlet from its original exhibition; a stack of books of self-portraits by Lee Friedlander stood alongside a self-portrait by Clément from 1977; a facsimile of Daido Moriyama’s 1972 Shashin yo Sayonara (Farewell Photography) was available for consultation; and films revealing, in the manner of a flipbook, Michael Snow’s 1975 Cover to Cover and Erik Kessels’s 2007 In Almost Every Picture #6 were playing. Proximity to such a rich array of publications – titles spanning from the 1960s to the present, produced in Germany, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and elsewhere – provoked a strong desire to take these objects in my hands, one by one, and while away what remained of the afternoon by exploring their insides. With my desire unfulfilled due to their presentation under glass, a series of questions began to form in my mind. What kind of experience is the viewer meant to have with these books? What is the story being told by their combination? Have we reached a point in the recognition of the photobook as a creative form at which the object’s symbolic potential can eclipse its use? My sense, at least, was that by transforming the object from one that is handled and “read” into one that is perceived from afar, the exhibition was making an important statement regarding the new status of the photobook within photographic history.

Prelude to the Exhibition. I met Serge Clément and Alexis Desgagnés, the exhibition’s curator, on a sunny Sunday afternoon in Montreal a few weeks later.1 They generously answered my questions and gave me insight into why they felt the project was important to undertake.

Clément has been interested in the photobook –as both an art form and an object of consumption – for over thirty years. Yet, as he described it, it is only in the past ten years that, with the publication of several comprehensive international and regional histories of the medium, his interest has taken a more formal turn: “It’s only over the past ten years, since publications have appeared that say ‘these books are important,’ that I’ve come to realize that actually, in spite of myself, I’m a collector. In fact, I don’t really feel I’m a collector – it’s rather that I’m fascinated by certain approaches, certain quests, and by the power of the photographic language.”

Whenever Clément went to VU to work in the centre’s darkrooms, he would bring books and share them with colleagues on site, among them Desgagnés. As he related, “We’d been discussing it for years. . . . It was one of the points of contact between Alexis and me. For a number of reasons – some similar, some different – we were both interested in the photobook and what it was becoming.”

Desgagnés’s fascination with the photobook has also been formalized by the genre’s rapid rise in popularity in recent years, and he has written several essays reflecting on this very phenomenon.2 As a member of VU’s administrative staff for over five years and the centre’s artistic director from 2012 to 2014, he is also invested in promoting the form at an institutional level. He firmly believes that it is still too undervalued in Quebec: “In Quebec, in the visual arts, most books are monographs. If you want to publish a book in the visual arts, because of the way the funding programs are structured it has to be conceived as a promotional tool. In my view, this is completely incompatible with the notion of an art book as a creative form in its own right.”

The crux of the problem with the current monograph-centred funding programs in Quebec is their requirement of substantial textual, didactic content; books that are exclusively image-based or in which text is used predominantly as a creative device are rejected outright. Disparaging the limitations of such programs, Clément added, “The monograph has its place, but it should not be the only type of book. . . . I think there are other aspects to the photobook.”

Speaking on the distinctiveness of the form specifically with regard to the exhibition as a medium of artistic expression, Clément recounted, “I’ve been making photobooks since I first started exhibiting. To begin with they stayed a bit closer to the kind of narrative I established in my exhibitions, but in the 1990s I began publishing them and perceiving them as different entities. Also, at around the same time there was the whole push within institutions of the photograph-as-painting, the unique photograph with its art-historical references. I saw this as one form of photographic practice, but there’s another that speaks more of narration, and the book occupies this niche. In my practice, this is something that I first understood and then tried to concretize. I put my exhibitions together in a different way, and soon I was creating books that had far more images than the corresponding exhibition – but it was the same project. It was two different ways of thinking about the same project. And the book was something other than an exhibition catalogue.”

As Clément and Desgagnés explained to me, the exhibition shown at VU was thus perceived as a way not only of recognizing the validity of the photobook as a distinct form of artistic creation, but also of capturing the role that it has played in the work and career of a particular artist.

The Exhibition as Self-portrait. When Clément and Desgagnés first began to work on the exhibition, a process undertaken largely by jointly going through and shuffling Clément’s extensive library, they found themselves reverting to canonical, somewhat impersonal systems of classification based, for instance, on a book’s country of origin or date of publication. At one point, they decided that they wanted the exhibition to be not just another general history of the photobook, but a reflection of how Clément views the idiosyncrasy of his own collection – and, by extension, of his own career – today. As Desgagnés commented, “The subjective dimension became clear. I felt that if we were going to do something like this, it needed to be placed in a contemporary context and we had to acknowledge the subjectivity of the collector – who is also a photographer. So we began diluting the categories and integrating Serge’s subjectivity in different ways.”

I asked them whether the selection of books included in the exhibition also functioned as the record of a shared history for the generation of photographers who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s. Without discounting my suggestion, Clément reaffirmed that the selection process quickly became grounded in his life and experiences. “Pretty soon Alexis asked me which books were the most significant. I talked about Richard Avedon’s book, which came before The Americans by Robert Frank. It’s a highly critical, disturbing portrait of America. It’s a book that has played a crucial role in my life, in the fact that I continue to take photographs. I think it has contributed to the importance of photography in my life.”

The inclusion of John Max’s print and exhibition pamphlet was one example of the strategy of bringing forth the idiosyncrasy of the collection and the personal history that it traces. Seen by Clément when he was a young student, Max’s 1972 Open Passport show, by proposing a radical approach to photographic sequencing, also played a decisive role in his development. Reflecting on Clément’s collection as the site of meaning, Desgagnés mused, “Walter Benjamin speaks of the collection as the outcome of a deep desire to prevent things becoming dispersed in time and space – in other words, in history.3 So every collection necessarily depends on or springs from such a desire, experienced by someone who wished to impose coherence on diverse elements of history. And in this case the coherence is fundamentally related to the fact that the collector was not a photographic dilettante, but someone who was searching for something particular in the specific realm of photography.”

Clément’s own photobooks, however, were absent from the exhibition, for the simple reason that he did not wish to legitimize these works by inserting them into an “official” history of photography. Yet, he observed, just as his photographs often contain an element of self-portraiture without him actually being represented, the exhibition contained layers emblematic of that genre. “In a sense, this exhibition is like a palimpsest of the self-portrait in all its many forms. It’s as if each of the books is a self-portrait of the photographer who made it. There’s Lee Friedlander, who photographed himself; but also Michael Schmidt – when he photographed Berlin in Waffenruhe, it was a self-portrait; when Richard Avedon made Nothing Personal, it was a self-portrait; The Americans by Robert Frank – it’s a self-portrait of Robert Frank. The Stage by Donigan Cumming is so powerful that it’s also a self-portrait. It may seem almost related, since it’s an exercise in mise en scène, but in this project there is a level that belongs to self-portraiture. And just as photographers create portraits of themselves by photographing all sorts of things, so do I construct my self through the books I choose. There is something of me in this process, just as there’s an element of self-portraiture in my own practice. The photographer doesn’t have to be present in the image for it to be a self-portrait. . . . It encompasses and unites diverse practices.”

Experiencing the Photobook. My question regarding the nature of the viewer’s intended experience of the photobook in the exhibition was posed toward the end of our interview. Clément responded, “It was practically impossible to offer the experience of each book in the exhibition. It’s another experience, the experience of the relationship between one book and another, or among a group displayed on a table. These were the keys to concentrate on, the relations among the books.”

While confessing his particular attachment to what one may call a first-hand, material experience of the photobook (especially in contrast to that provided by online publications), Desgagnés offered that the kind of frustration one might feel by not being able to consult the books on view is representative of a kind of fetishism of the image: “Why would people want so desperately to consult the books on display? Simply because we are all avid consumers of images, about which we have what amounts to a fetish. One of our goals was to assert clearly that the photobook can attain the status of an artwork. And by presenting the books in a way that prevents the visitor from reading them, we wished to create a frustrating experience that would trigger this fetishistic desire.”

For Clément and Desgagnés, it was precisely because the exhibition did not allow for perusal of this rich collection that the validity of the photobook as a form of artistic creation was affirmed. But what it also raises, for me, is the question of whether there is not just one possible experience of the photobook – even, I would add, when they are individually handled and read. There is no “right” way to read a photobook, just as there is no “right” way to read an exhibition.

I think that this exhibition’s originality lay partly in the fact that it translated one form of expression to another, thereby encouraging viewers to reflect on the distinct properties of each. Sharing his thoughts on the difference between these two modes of expression, Desgagnés added, “In my view, the photobook and the exhibition are two media for disseminating photography that are divergent rather than complementary; they’re two entirely different modes of thinking. The book has a very evident narrative dimension, but when you try to create the same thing in space, you really need a space that is appropriate to creating an experience equivalent to that of a book. So you may as well approach the exhibition space as an anti-narrative space, something much more abstract. And then it gets interesting, because you have an immersive visual experience.”

Remembering my own experience of the exhibition, I reflected that I had indeed felt immersed in a constellation – a constellation composed of images and objects whose role in the story has been central.

2 See, for example, Alexis Desgagnés, “The Quebec Photobook: Thoughts on a History to be Uncovered,” trans. Käthe Roth, Ciel variable 97 (Spring–Summer 2014), 55–60; Alexis Desgagnés, “John Gossage – The Photobook: Reflections on Several Recent Projects,” trans. Käthe Roth, Ciel variable 95 (September 2013– January 2014), 62–66.

3 See Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt and trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 59–67.

Zoë Tousignant is a historian of photography and independent curator working in Montreal. She is a recent graduate of the PhD program in art history at Concordia University. Her research interests revolve around the dissemination of photographic culture, both historically and in the present.