[December 20, 2023]

By Louis Perreault

Books are finishing points. As a form, they seem to say, here is what has been achieved, all paths lead here, and all equivocations end here. Yet, how long they will last – their life expectancy – is impossible to predict. There is thus a paradox in the act of producing a book – that of bringing a creation to a close yet offering it a future and a certain permanence.

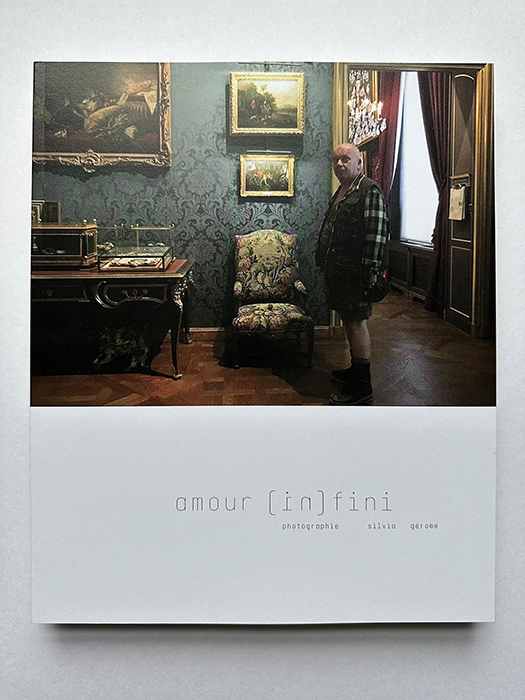

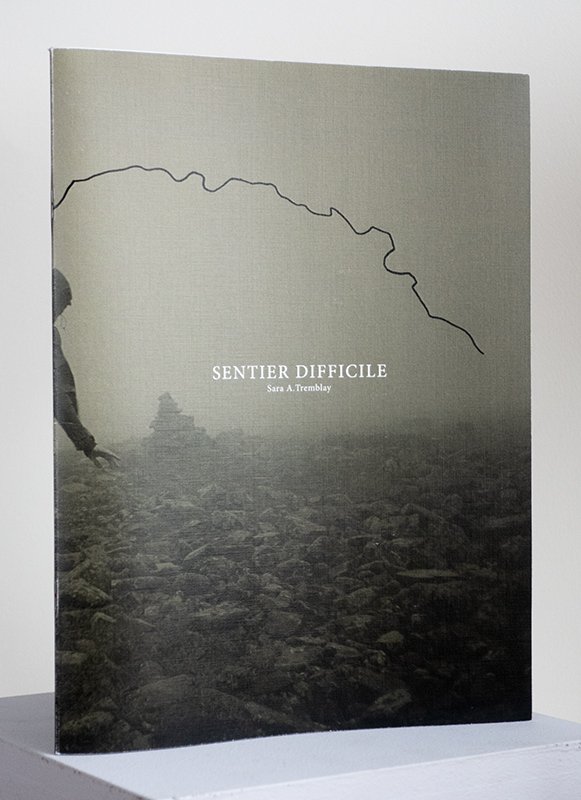

These days, we are faced with a constant flow of new publications, most of which strive to carve out a prominent position in the cultural landscape and aspire to inscription in cultural history. Others come forth more humbly, with motivations that seem to be linked to the completion of an experience rather than to the permanence of the work for which they are the means of dissemination. Silvia Gérome’s amour (in)fini and Sara A. Tremblay’s Sentier difficile seem to arise from this more modest desire, relieved of the creator’s ambitions.

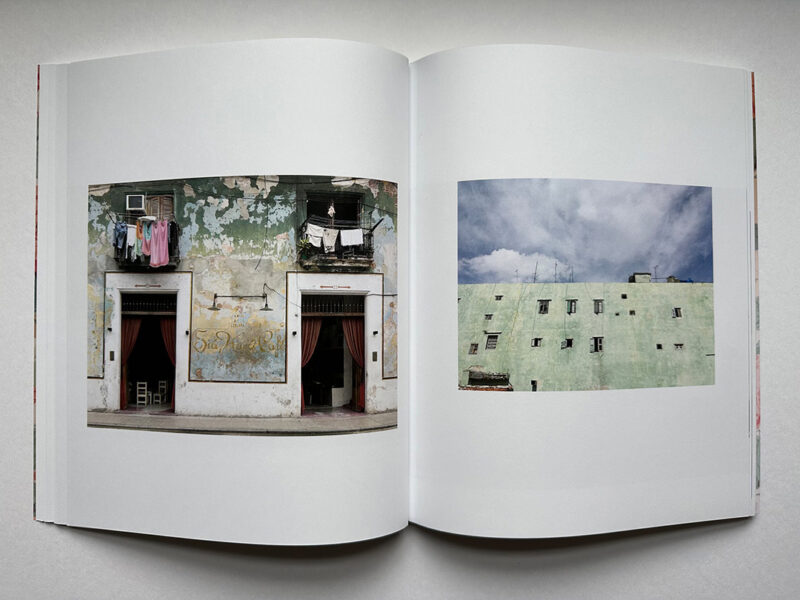

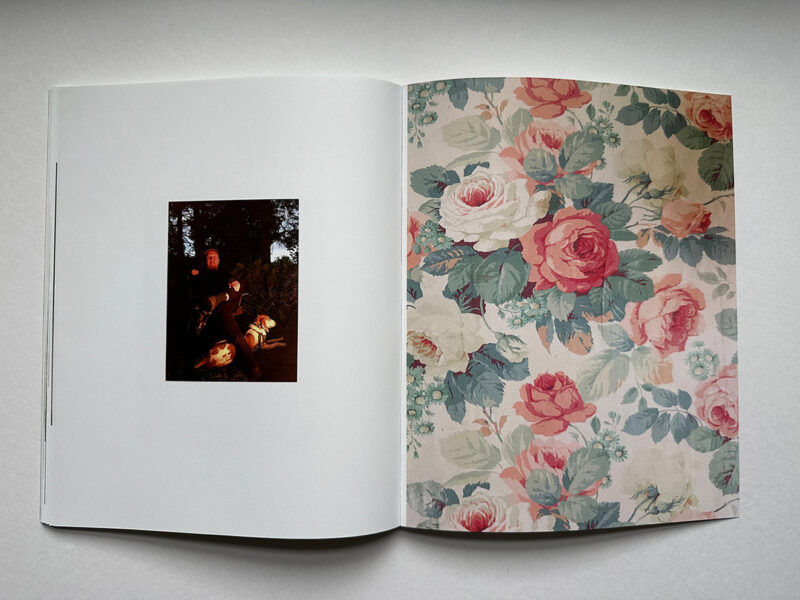

In mourning. Silvia Gérome has been dabbling in photography for many years. Her images combine the formal requirement of the profession and the lightness of an amateur’s approach. When she points her lens at the façade of a café in Havana, we might be reminded of the superb colours in Robert Polidori’s photographs taken there at the turn of the millennium. When she makes a portrait of her lover sitting near a campfire, we recognize the experience conveyed in the image without having actually been there.

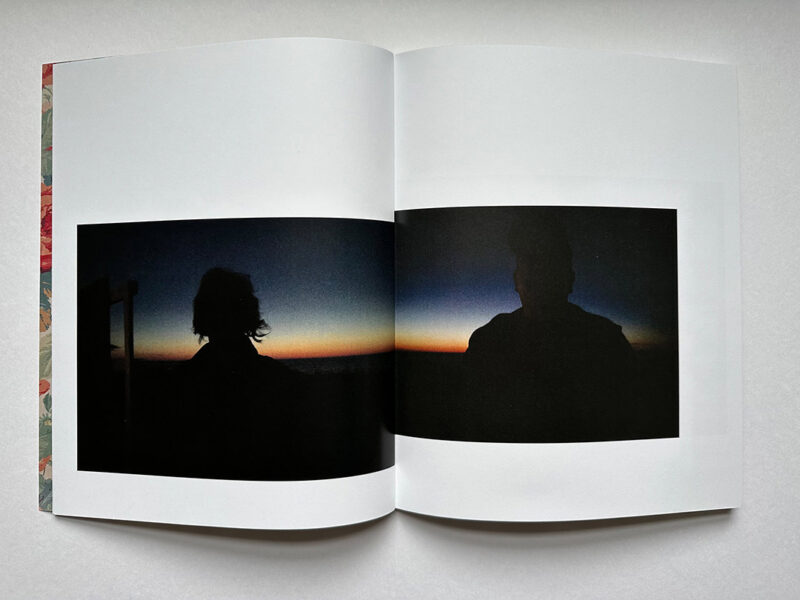

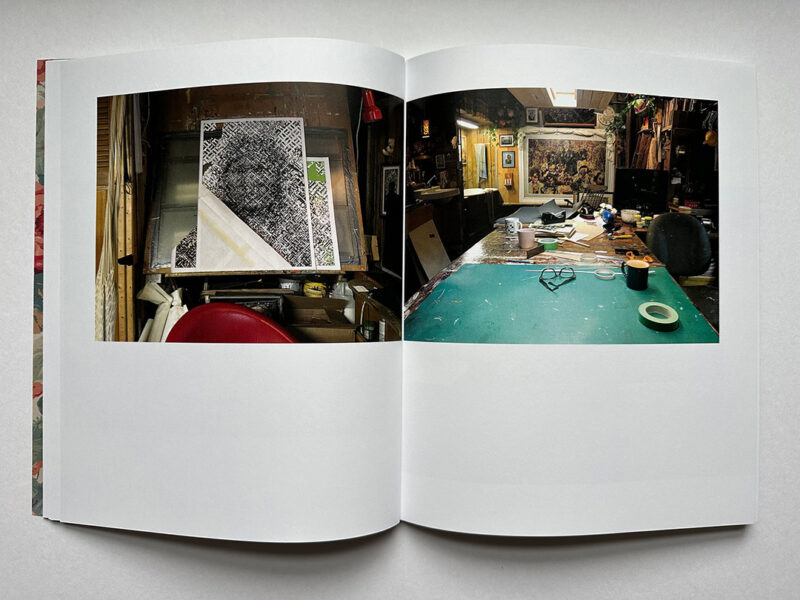

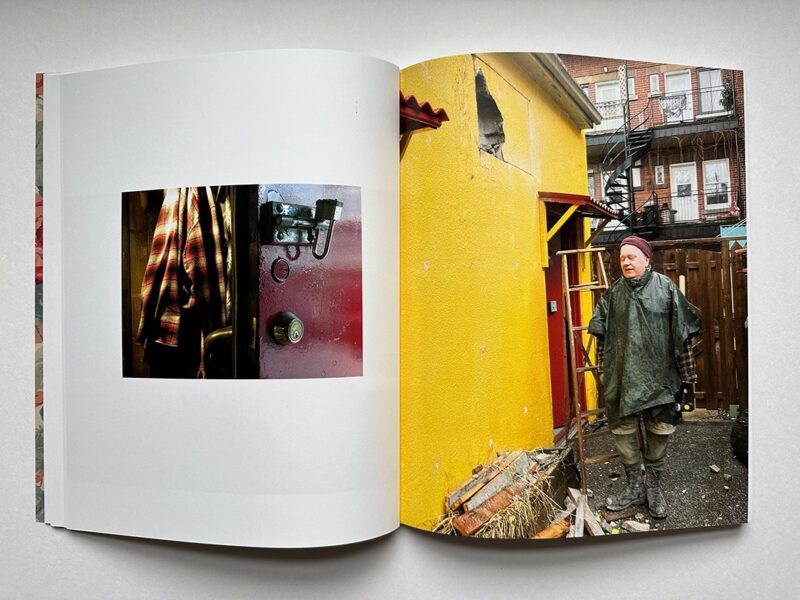

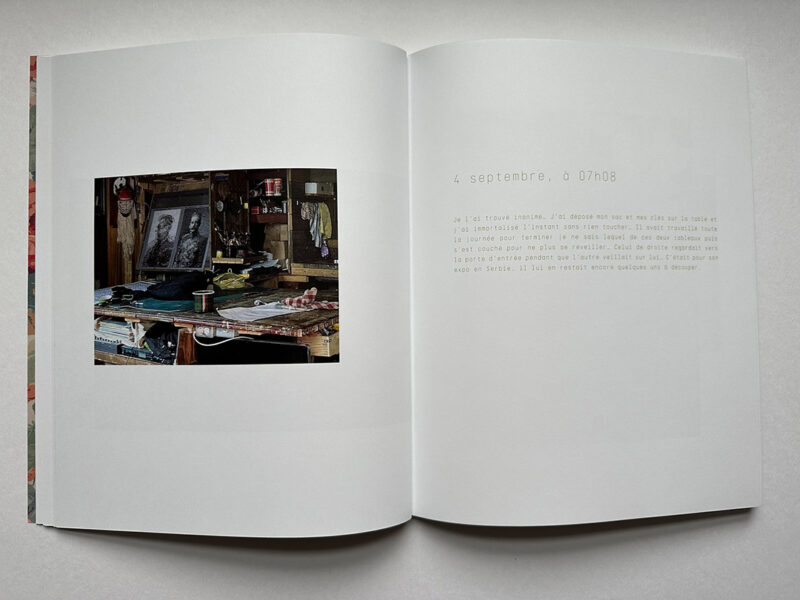

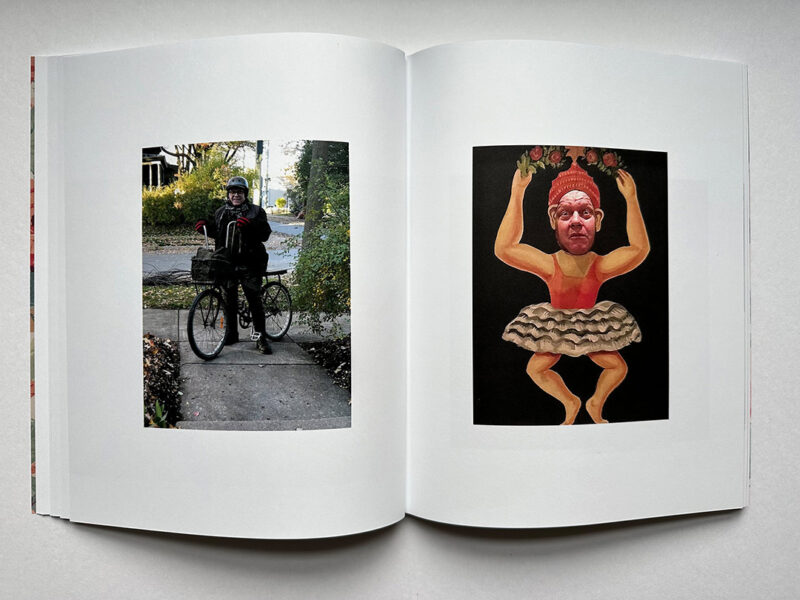

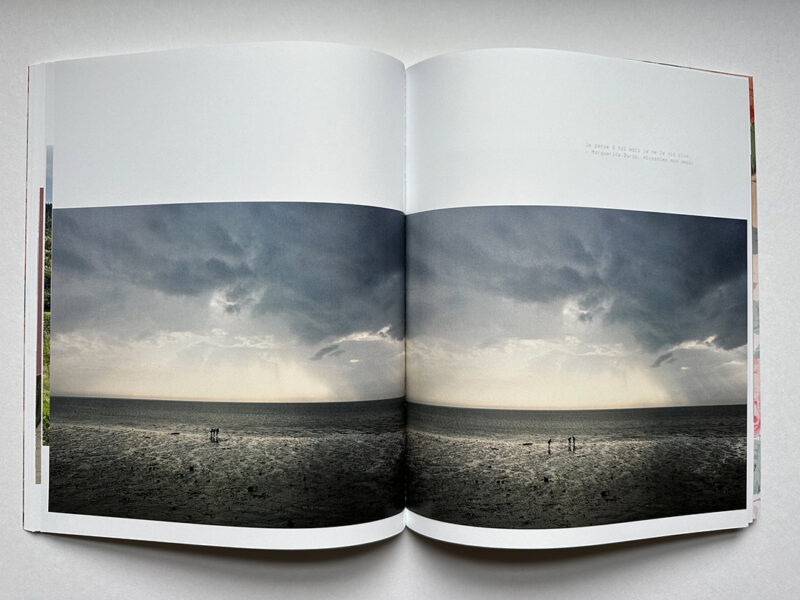

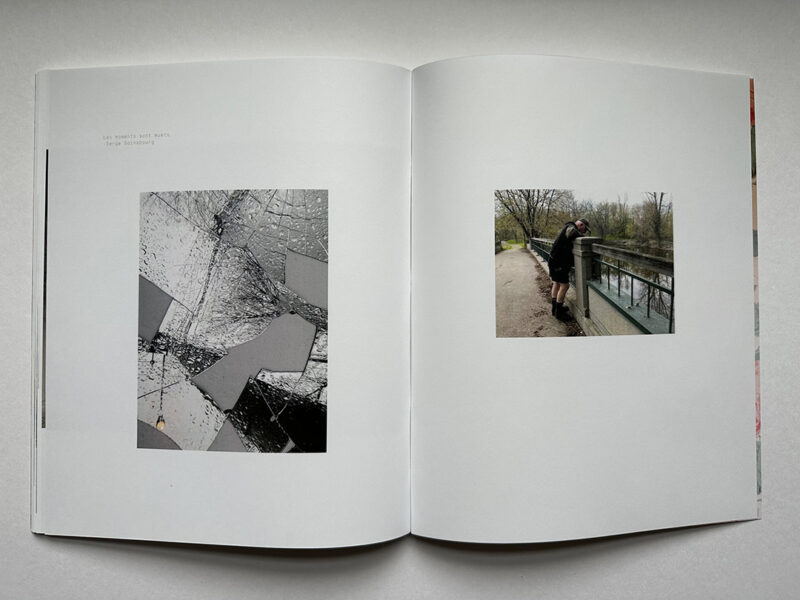

In amour [in]fini, Gérome is aiming neither to imitate the greats nor to create a personal diary of her comings and goings. Rather, she emotionally reveals her mourning for her spouse, Patrick Henley (alias Henriette Valium, a well-known alternative comic-book artist), who died suddenly in the night of August 31–September 1, 2021. Henley, with whom she had long shared her life and “an infinite love,” inhabits the pages of the book,1 which is both a souvenir album and a poetic offering. She brings us into his creative space and into the couple’s travels, while conveying Henriette Valium’s eclectic and quirky world through a few portraits captured in the studio or in touching – and sometimes funny – moments of daily life.

Although this memory exercise isn’t utterly novel, it is nevertheless imbued with a real artistic intention. How can the liminal experiences that mark a life’s great upheavals be expressed, especially when they are devastating and grievously hurtful? As we navigate between shock and acceptance, can creation be a lifesaver, palliating the pain? These questions inhabit us as we read amour [in]fini, making us particularly attentive to the spaces, things, and moments captured. What can be said about the image titled photo 02/09/2021, constat du décès de Patrick, Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, 2021, showing a studio table, a bunch of keys, a few rags, and two canvases leaning against a sort of easel? As we read, on the recto page, the story of the discovery of Henley’s body the day after his death, the photographic gesture is striking. It testifies to how many photographers make picture-taking an act of mediation, as if a visual perusal of reality could channel some shred of truth that would otherwise elude us.

Post-mortem. For years, Sara A. Tremblay has been creating a body of work that emerges from her life and is deployed across the vagaries of friendship, love, and creativity. Her works often bear witness to the process that marked their conception: summer brings the garden into bloom and the house’s sitting room is transformed into a studio in the fall, in order to pursue the creation of a flamboyant ode to the regeneration of the living2. We see Tremblay in the high grass or under the summer sun, taking part in this great natural cycle and offering care and attention to plants, as if they were members of her own family and the earth that feeds them were just as essential to her own survival.

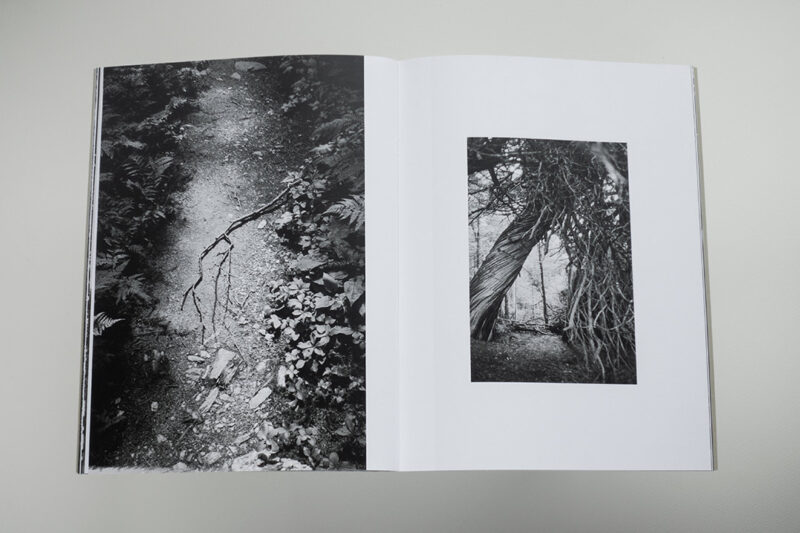

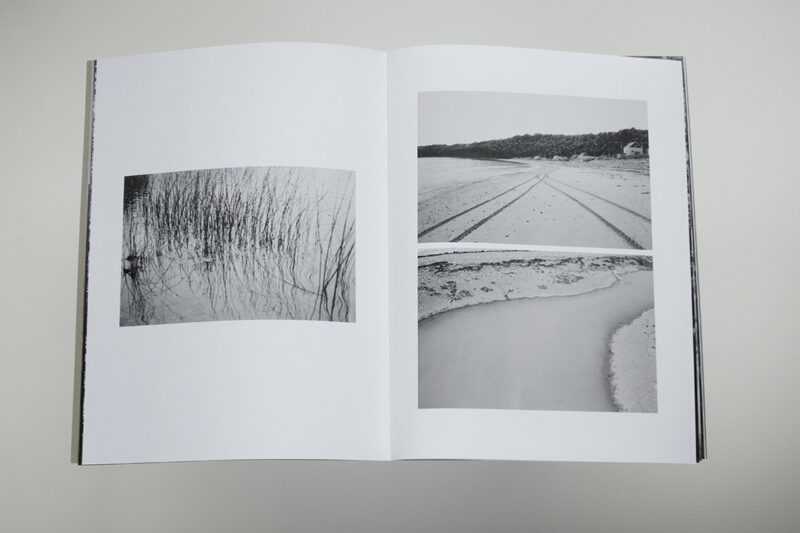

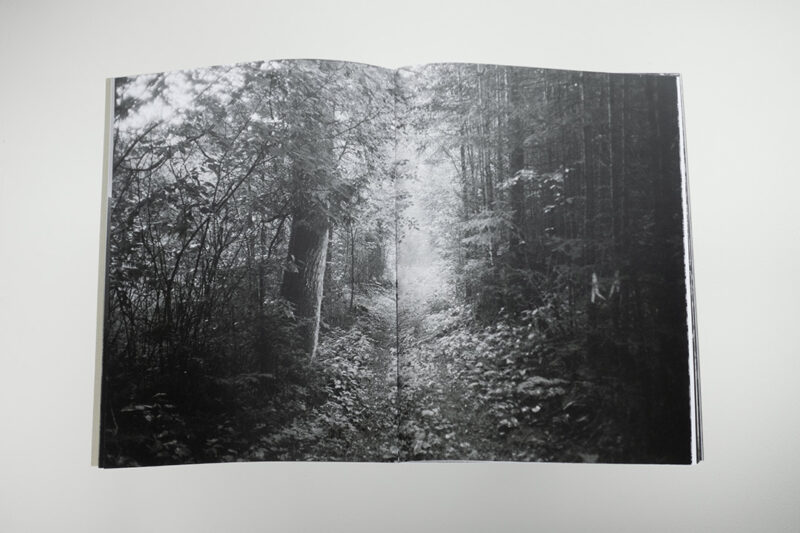

So, it isn’t surprising that a forty-day-plus hike along the Gaspé Peninsula section of the International Appalachian Trail became the pretext for creating a work composed of webs of lichens, evergreen boughs, waterfalls, narrow paths, and tangled landscapes. Or, might it be said, more fairly, that it was creation that led to the hike? No matter; here again, life and creativity overlap without distinction. In fact, in summer 2016 Tremblay was selected by Les Rencontres internationales de la photographie en Gaspésie to produce a work inspired by the region’s landscape. In company with her life partner, the artist Drew Barnet, she took to the trail and found herself almost immediately engulfed in the dense Gaspé woods somewhere between Matane and Parc Forillon.

Sentier difficile offers a record of this forest crossing. It was a challenge, we can guess, that tested the couple’s physical and psychological limits even as it offered them a unique creative context. After the result of this work was displayed in Gaspé and Kamouraska in 2017, the images seem to have gone dormant while other projects claimed Tremblay’s attention. What inspired her to revisit these photographs in 2023, during a micro-publishing residency at Centre SAGAMIE? We would have to ask her to really know, but a short sentence at the end of the book gives us a clue. She writes, referring to the couple’s experience of walking, “This notebook humbly presents a visual narrative, a metaphor for their loving relationship, and a tribute to these two difficult paths.” Is it thus a desire to wrap things up, to assemble bits of memory, to pay tribute to what was, and to formulate – with the awareness of the imperfection of all transmissions of the past – the final statement on a unique adventure?

In the granular texture of photographs captured with a 35 mm camera – in these collapsed tree trunks, these small stretches of water, and this wonderful waterfall hidden deep in the peninsula; in this vegetal anarchy and this delicate baby fern growing at the edge of the trail; in the gesture of a hand accidentally appearing in the frame of a photograph and that, deliberate, showing the twisted body of a piece of driftwood; in the intrusion of light caused by a deficient seal in the camera and the two little shadows that appear in the first image in the book – we ultimately see a sort of elliptical, allusive process. In the end, these living beings and things refer to a sympathetic experience of nature by two lovers seeking a semblance of the absolute, entangled in the complex meanders of their relationship and those, just as dense, of creation. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 See Poids, plumes: https://www.saraatremblay.com/Poids-plumes.

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.