[Winter 2019]

By Bénédicte Ramade

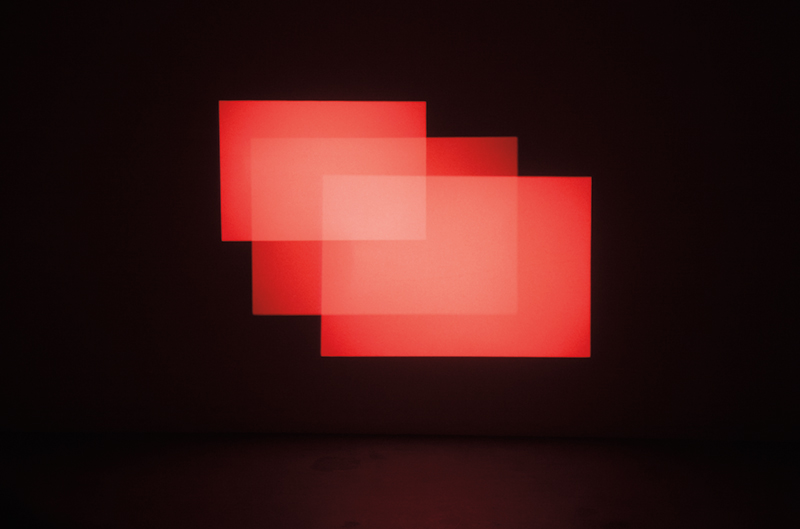

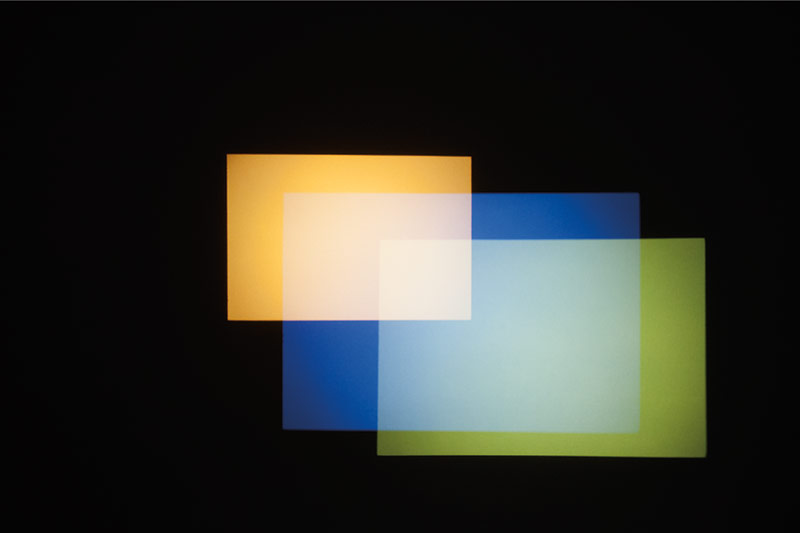

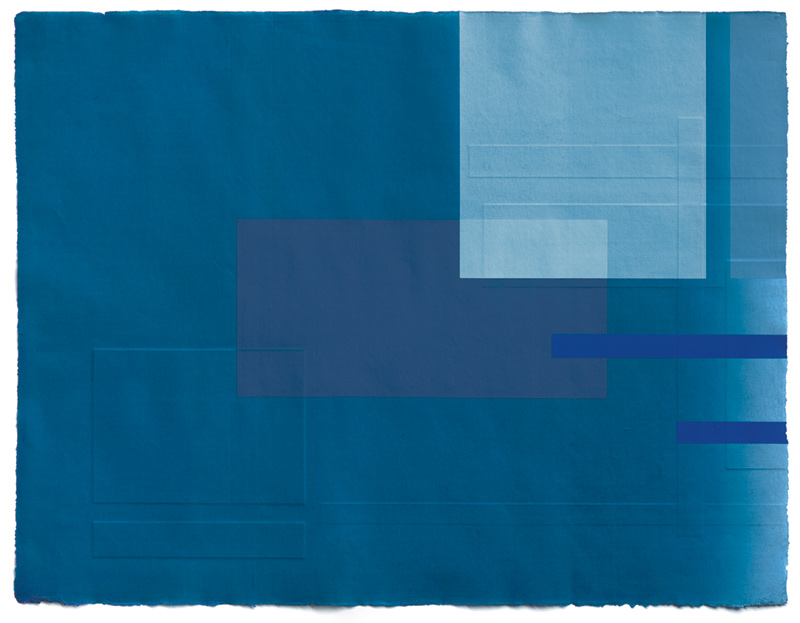

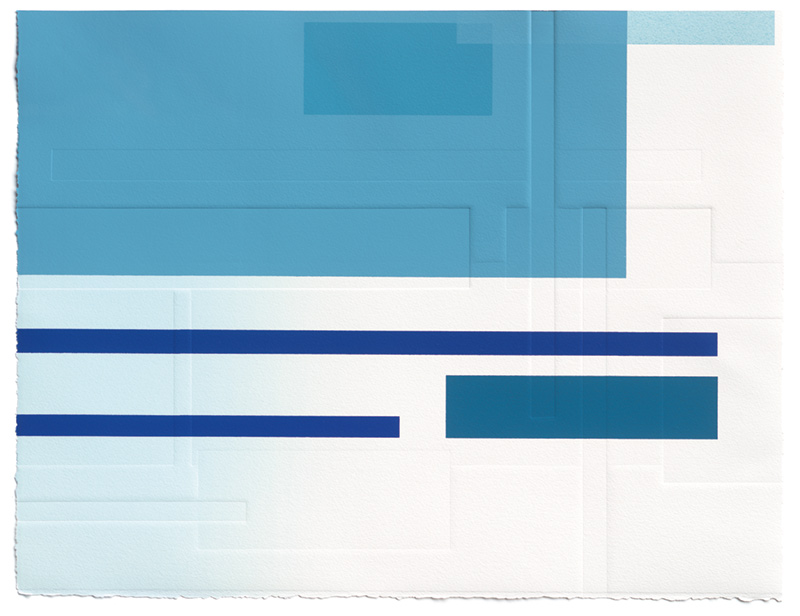

In one of his most recent series, Réponses à la peinture, Yann Pocreau establishes an interplay of brightly coloured superimpositions, transparencies, and opacities. Hot pink, mauve, navy blue, grey, burgundy, and black clash to offer the fourth “solution” in the series (Réponse à la peinture 04, 2017–18), like a mathematical equation the logic of which is hidden from the spectator. Moss green, turquoise, saffron yellow, grass green, and lime green intersect, neutralize each other, and appear in Réponse à la peinture 8 (2017). In this formalist interplay, a tribute to hard-edge, the series of digitalized photograms is immersed in the fundamental world of colour, primarily the prerogative of painting. Early in its history, photography had been deprived of colour, as it was not technically possible to fix or print that part of the light spectrum. And yet, pioneers of the medium were obsessed, from the beginning, with the ideal of completing their processes through the addition of colour. Pigments, filters, oxidation – the conquest of colour was slow and frustrating for photographers. It is a conquest that Pocreau takes on through geometric abstraction, in works in which he condenses the tension between colours, on the one hand, and black and white, on the other. As Nathalie Boulouch explains in Le ciel est bleu. Une histoire de la photographie couleur (2011), rather than surrendering to the nonrealism of monochrome black and white, photographers had attributed to it a deeper analytic value than colour, deemed boringly naturalist: “[Colour] portrayed the reality of the world, whereas black commented upon it.”1 As long as it could not be captured, the thinking went, one might as well shun it. No matter. Amateurs would take on the job, in projections, following the invention of the autochrome process by Louis Lumière in 1903.

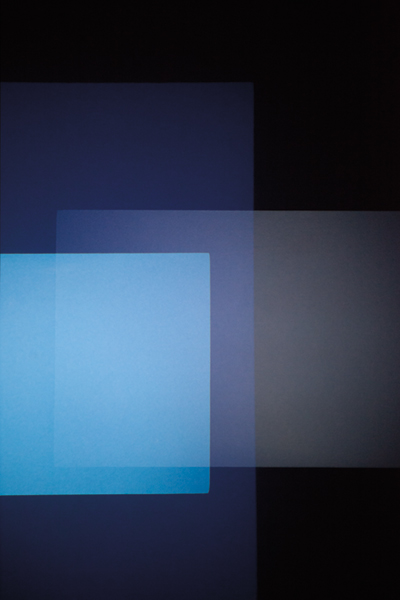

Additive or subtractive syntheses – that is exactly what Pocreau deals in. In Croisements (2014), he uses no fewer than 720 slides, distributed among nine projectors, to compose – through superimposition, interference, saturation, and blackening – a rhythmic environment of colours, fleeting combinatory apparitions. The twenty-four colours that were used to calibrate each set of monochrome images, repeated three times per slide carrousel, came from a chart published by X-Rite, used extensively by Kodak, that Pocreau had exploited previously in Color Chart (2013–15)As if in a chemical formula that becomes more and more complex, the benchmarks in this chart were projected, enlarged, for Pocreau to photograph. It is a photographic tautology that pushes sensibilities to their limits, confronting the definition of colour with the capacities of lens and slide film, and thus explores the history of colour-photography manufacturers that dominated the sector in the twentieth century. Les couleurs argentiques (2016) is composed of four sheets of unfixed silver-halide paper, each from a major manufacturer: Ilford, Kodak, Agfa, Fuji. They display four perfectly distinct colours: two are bluish, one green, and one ochre, almost as if they were the signatures of these brands, providing a good demonstration that colour is not an exact science. The colour is thus left on its own – a chemical formula revealing the subjectivity of its condition.

Pocreau also forces the subtraction further, revealing a true inner life through planes left without fixative, placed against sheets on which the sensitive process has been stopped in its tracks: Fuji’s delicate bluish glissando and Kodak’s garnet (Variations progressives, 2016). These colours were not formulated by paint manufacturers, and that’s the secret. They are colours that he has not controlled, from which he humbly agrees to disentangle himself, similar to how photographers position themselves in relation to their medium. And when

Pocreau was invited to collaborate with astronomers at the Observatoire du Mont-Mégantic in 2018, the images produced were abstract, rainbow-coloured prints of skies with blacks impenetrable to common mortals (Diffractions, 2018). Furtively, Pocreau rubs up against science without didactics, without hiding behind the narrative of process and procedures, of which he makes neither display nor pretext.

Pocreau takes us through the technological history of colour photography without nostalgia. And he reminds us that it is not, by any means, evidence. As Georges Roque observes in Art et science de la couleur, the perception of colours is not a natural, anhistorical, or individual phenomenon, but a cultural, collective, historical activity.2 It is a cognitive and emotional process that invites theories in both science and art: optical questions are clearly linked to art, whereas subtractive mixing (of pigments) and additive mixing (of coloured light) are the domain of science. Pocreau proceeds no differently. In Ce que le noir contient (2016), an ink-black diptych allows coloured gradations of cyan and yellow – two components of trichromy that, paradoxically, generate a bottomless black – to encroach gradually on the edges. The result of an extreme saturation of colours, this black is a highly concentrated synthesis, the antithesis of a “black hole” – an absence. Only the yellow and blue have escaped, leaving a glimpse of a gentle gradation. Whereas paints seek to eliminate black and increase the luminous intensity and purity of certain spectral colours (red, orange, yellow, blue, green, violet),3 Pocreau constructs his blacks by summoning all the means of colour.

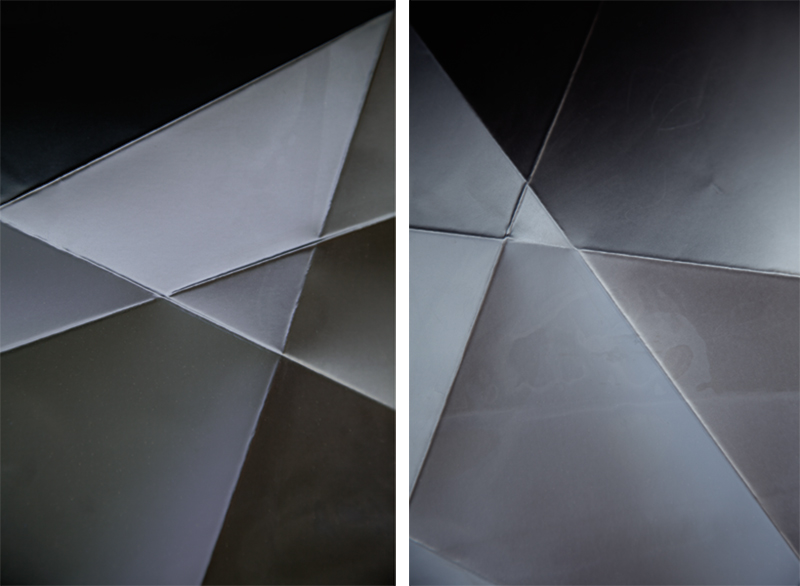

Pocreau’s body of work is built around his interest in colour combined with light. It began with his pictures of construction sites (Chantiers, 2012), in which he removed the context to deliver a range of washed-out greens, divided up by black shadows and whites so luminous that they form planes. Already, he was building his grammar of putting surfaces and spaces into tension. This principle of construction and deconstruction rules over his most abstract photographs, over the complex procedures derived from the fundamentals of his medium: light, emulsions, exposures, photosensitive paper. He constantly folds and refolds his material, as he did in the eponymous series Replis (Refolds, 2016), allowing us to see on sheets “untouched” by a photographic image the recording of manipulations and constraints applied to the sensitive paper-material. He shows us a medium stripped bare, in which colour can no longer be distinguished from black and white – the tandem of an exploration of the qualities intrinsic to photography for which painting has no answer. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Georges Roque, Art et science de la couleur (Paris: Gallimard, 2009).

3 Georges Roque, Quand la lumière devient couleur (Paris: Gallimard, 2018), 8.

Bénédicte Ramade is an art critic and contemporary-art historian, with specific expertise in environmental issues. She also produced exhibitions and catalogues: The Edge of Earth: Climate Change in Photography and Video for the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto (2016), and Karine Payette, at the Salle Alfred-Pellan in the Maison des arts de Laval (February–April 2019). She published “La photographie en elle-même,” in the first monograph on Yann Pocreau, Sur les lieux/On site (Musée d’art des Laurentides and Expression). Ramade is currently a lecturer in the Department of Art History and Cinematographic Studies at the Université de Montréal and the School of Visual and Media Arts at UQAM.

Yann Pocreau was born in Quebec City in 1980, and he lives and works in Montreal. In his recent research, he has explored light as a living subject and its effect on the narrative thread of images. His work has been presented in Quebec, the United States, and Europe (France, Belgium, Turkey) and is in several Canadian collections. A major retrospective, Sur les lieux/On site, was recently presented jointly at the Musée d’art des Laurentides, in Saint-Jérôme, and Centre Expression, in Saint-Hyacinthe, accompanied by the first monograph on his work. He is represented by Galerie Simon Blais, in Montreal. yannpocreau.com

IN ADDITION TO THIS ARTICLE :

Inventer la couleur — La Fabrique culturelle. Video Clip. February 2019.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 111 – THE SPACE OF COLOUR ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Yann Pocreau, Les surfaces de lumière — Bénédicte Ramade, The Life of Colours ]