[Summer 2019]

By Bruno Chalifour

Some two years after Nathan Lyons’s death, on August 30, 2016, the George Eastman Museum (GEM) is presenting an overview of the life’s work of one of the central influencers of American photography in the second half of the twentieth century:1 a photographer exhibited in the most prestigious museums since 1960, a curator, an editor, an educator, an assistant director at the George Eastman House, a founder of the Visual Studies Workshop and its international magazine Afterimage, and an instigator and co-founder of the Society for Photographic Education – to list just a few of his many activities in and for photography. The idea for In Pursuit of Magic was germinated in 2013 and started as a collaboration between Lyons and the assistant curator at the GEM, Jamie Allen. The latter had to take over the project in 2016, with assistance from Lyons’s spouse, Joan, a celebrated printmaker and book artist, and the GEM’s chief curator, Lisa Hostetler. As a result, the exhibition in its final form oscillates between retrospective and first exhibition of Lyons’s foray into digital colour photography, between didactic homage and sometimes puzzling experimentation…

Nathan Lyons: A Life in Photography. Nathan Lyons was born in New York City in 1930. After two years as a US army photographer in Korea, he enrolled at Alfred University in New York, from which he graduated in 1957 with a BA in literature. During that period, he took art classes, including photography with John Wood, who had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago (also known then as the New Bauhaus following Moholy-Nagy’s role in its creation) under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind. Wood had a strong impact on Lyons, who then decided to go to Chicago. En route, he stopped in Rochester to meet Minor White, who had just left the George Eastman House to join the faculty of the Rochester Institute of Technology. White informed Lyons that the director of the museum, Beaumont Newhall, was looking for someone to replace him. This is how Nathan Lyons joined the staff. He left his position as assistant director in 1969, when he “was resigned” by a museum board too conservative for his ideas.In his twelve years at the GEM, Lyons curated key exhibitions championing a growing renewal in American photography: Photography ’63, ’64, and ’65, The Persistence of Vison (1967), and Vision and Expression (1969), as well as Lee Friedlander (1963), Dave Heath (1964), Aaron Siskind (1965), the historical Contemporary Photographers Toward a Social Landscape featuring the work of Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, Danny Lyon, Duane Michals, and Garry Winogrand (1966), and Photography in the Twentieth Century for the National Gallery of Canada (1967). He developed numerous educational initiatives, instigating the foundation of the Society for Photographic Education (1962) and Oracle (a yearly symposium for historians and curators in photography), organizing the creation of sets of transparencies from the museum archives for schools and universities, creating a book-bus that would lend photobooks to educators, and publishing catalogues and anthologies, among them Photographers on Photography (1966), a compilation of seminal texts on photography. As soon as he left the museum, Lyons founded the Visual Studies Workshop, an alternative structure offering an MFA program, workshops, a gallery, a magazine (Afterimage, 1972–2018), a research centre with one of the best collections of artist books in the country, and a publishing company. From the early 1960s to the late 1980s, his impact on the medium more than equalled John Szarkowski’s at MoMA: Lyons also trained numerous photographers, educators, and curators. His writings on the medium include considerations on the snapshot, the social landscape, photography and the picture experience, the photographic sequence, visual literacy, and more.2

Nathan Lyons, Photographer. The vast majority of Lyons’s work, from the 1950s to the early 2000s, is in black-and-white analogue photography. In the early 1960s, he shifted from medium and large format to 35 mm. As shown in In Pursuit of Magic, his photography belongs to the American tradition of the “fine print,” with its deep blacks and subtle grays.

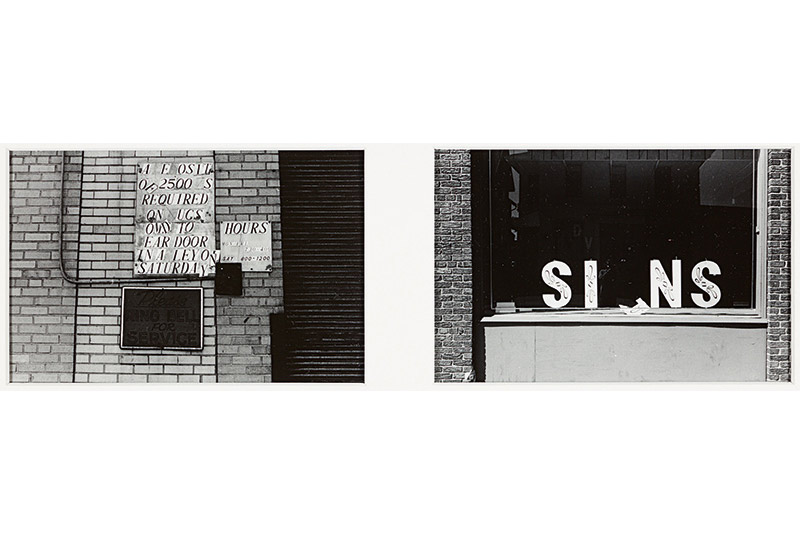

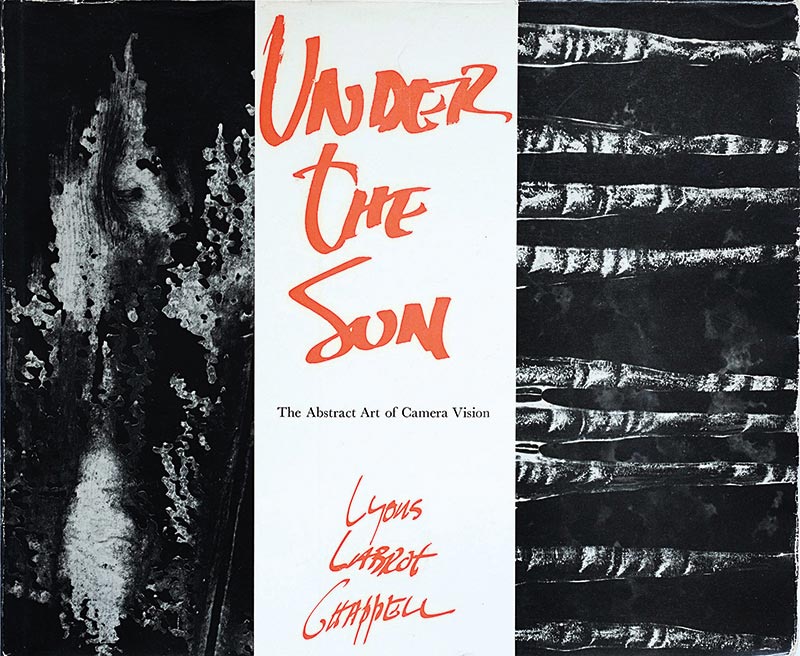

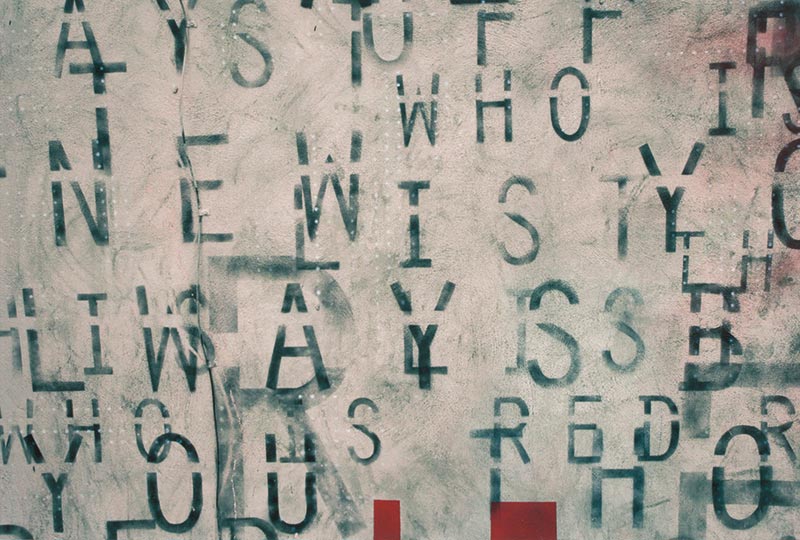

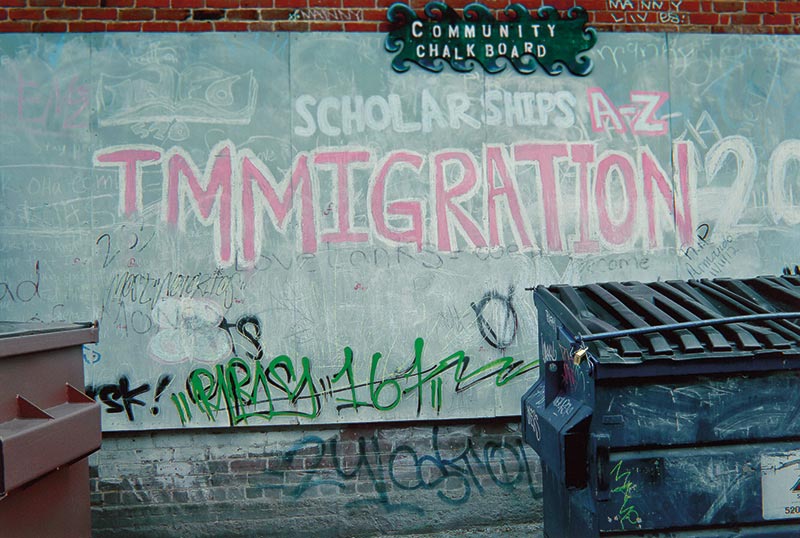

In Pursuit of Magic begins with a few large-format photographs from the late 1950s exemplifying Lyons’s close relationship with Minor White, Walter Chappell, and Aaron Siskind. As an introduction to his philosophy, on the wall facing the entrance to the exhibition is a quotation excerpted from Under the Sun (1960), a book-catalogue that he published jointly with Walter Chappell and Syl Labrot: “The eye and the camera see more than the mind knows.”3 On the first two short walls starting the exhibition (on the visitor’s right in the first gallery) are three abstract photographs from Under the Sun, his first major series. The rest of the gallery – and of the exhibition – is dedicated to a subject that would preoccupy him during the following decades: a reflection on the urban social landscape (seen from the sidewalk). Over fifty years, Lyons established a subspecialty of street photography focusing on cultural vernacular signs, graffiti, murals, spontaneous ads, and telescoping objects displayed in store windows that most of us overlook. He then became a witty, detail-oriented flâneur, gleaning visual evidence – trouvailles – of contemporary vernacular culture, in line with his advocating for “snapshots” as serious sources of inspirations for the artist. Beyond Atget, considered a visual precursor, Lyons also found inspiration in the writings of J.B. Jackson on the vernacular landscape and in the photography of Lee Friedlander and, above all, Robert Frank.

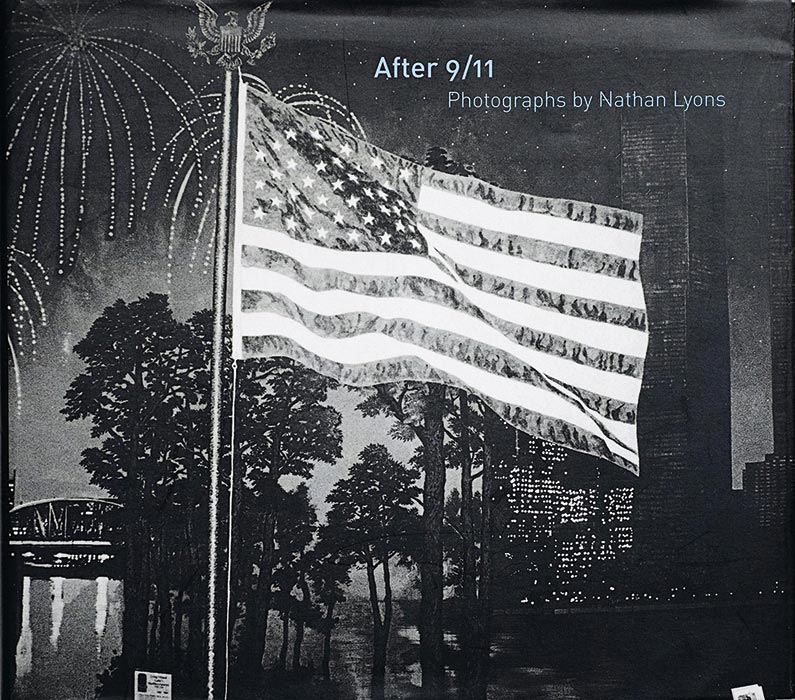

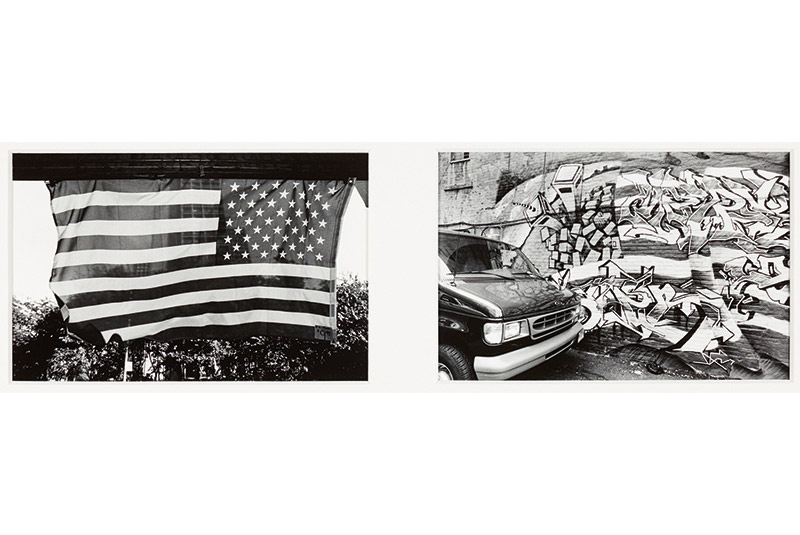

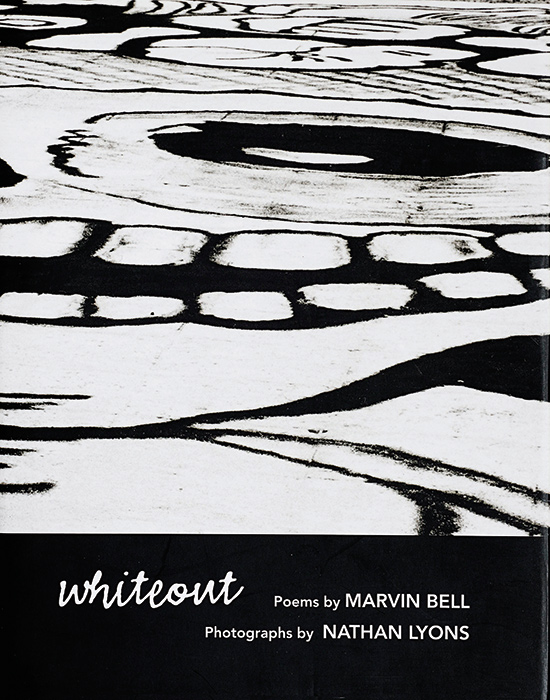

Frank’s seminal photobook, The Americans (1959), played a considerable role in Lyons’s photography and teachings. In his view, for photography to be established as a full-fledged visual language, the photographer had to go beyond the single photograph. This realization was the source of his considerations and theories on the organization and presentation of photographs as groups whose meaning is greater than the sum of its components. From closely studying The Americans, he developed his own concept of “visual literacy,” devising a completely self-sufficient visual language independent from spoken and written language. Following this approach, none of his books, from Notations in Passing (1974), to Riding First Class on the Titanic (1999), After 9/11 (2003), and Return Your Mind to Its Upright Position (2014), relies on text. They all display groups of black-and-white 35 mm photographs separated by a blank page and usually starting with a subject and composition that is repeated and conjugated at the beginning of each group. It is a technique that mirrors Frank’s use of the American flag as punctuation in his “sad poem sucked out of America.”4 Each group is then composed of two images (diptychs), one on each facing page, between which Lyons creates a dialogue, generating meaning beyond the single image and investigating the possibilities of the “extended frame.” His books, in their totality, should be considered one long sequence whose meaning relies on accumulation and the dialogue between each of the sub-sequences that compose them. In fact, the four books mentioned above could be joined (and exhibited) to define an earnest and witty life-long flânerie, exhibiting their author’s preoccupations and their evolution as well as the growing sophistication of his style.

In Pursuit of Magic celebrates these stages, dedicating wall space to images from these books in the first gallery and the beginning of the second one (roughly one wall). To compensate for the lack of wall space for such an endeavour, the curators have thoughtfully displayed each book at the beginning of the respective book-sequence. They are free-standing and can be easily perused by the curious visitor. However, the display in the first gallery is designed to flow from right to left in an anti-clockwise movement, a decision made because of the combined geography of the room itself and the visitors’ observed clockwise (sheep-like) progression – it is the shortest way to the entrance to the next gallery – which leads them to skip the rest of the room. This means that the works are displayed here in an order counter to the usual reading movement from left to right. As a result, the diptychs and sequences are read backwards, which is not exactly conducive to a real grasp, not to mention understanding, of Lyons’s style and essence. Moreover, other choices interfere with our understanding of his work and thinking: instead of starting, as all of his books do, with a single image followed by diptychs, the wall space dedicated to Notations in Passing starts abruptly with a diptych. The normal progression of Lyons’s sequencing, one supposed to generate extra meaning, and its fundamental connection to Robert Frank’s The Americans are lost, a problem compounded by the absence of any reference to The Americans.

The second gallery, about four times bigger than the first one, begins with Lyons’s last two sequenced books (After 9/11 and Return Your Mind). They occupy just under a third of the space, the rest of which is dedicated to his foray into digital colour photography. There is, however, a puzzling exception consisting of two panels of six black-and-white diptychs taken in Mexico whose only connection to the rest seems to be illustrating the word “diptych,” which is finally defined on the wall next to them. After the visitor has already seen at least four score diptychs, the presence of the definition and photographs here feels untimely, if not futile. It is an even more puzzling choice given that the photographs involved were never part of any book or group of photographs sequenced by Lyons! We then enter an area of this second gallery that is devoted to ninety-one colour photographs taken in the last ten years of Lyons’s life. This project was never completed, which means he did not have the time to select each photograph, sequence them, or even print them all. His original goal for the exhibition had been to show only this new work; unfortunately, again, the selection and display (we cannot speak of his sequencing here as he did not participate in it) were left to a young curator informed only by her conversations with Lyons and then with his wife. As the reader may have guessed at this point, the result is disappointing. It misses the essential elements of Lyons’s photography: selection and sequencing. It is a compromise resulting from the difficulty of handling complex work without the author being present. Nevertheless, the usual subjects of his photographs are there: road signage, murals, graffiti, store windows, spontaneous or celebrations recorded on walls or sidewalks, and so on, to which a new element has been added, and with which it sometimes interferes: colour.

Nathan Lyons in Pursuit of Colour. Colour was the final central issue in Lyons’s photography. Having worked in black and white all his life, he suddenly veered off into colour – and not just colour but digital colour, which involved a new technology, new knowledge, and a different practice. It’s not so easy to steer a motorboat after steering a sailboat for many years! Interestingly, in a conversation with Rick Hock and Carl Chiarenza published in the spring 2007 issue of Image (George Eastman Museum), Lyons declared, “I think many photographers working in black and white had to learn how to control their medium; today any digital photographer is going to have to learn how to control the medium as well. That’s part of the responsibility in being an image-maker. There were endless numbers of poorly rendered prints made in black and white. We saw the same thing in the evolution of color processes. It made a world of difference if you were really on target with the print. As Carl [Chiarenza] alluded to, if the color was off, it was a distraction.”5

During the first stage of conception of the exhibition (2013–16), when he was experimenting with digital colour photography, Lyons was in his eighties and underwent life-threatening health crises. It seems that he did not have the time to acquire the necessary control and mastery of the new medium that he had discussed in 2007. The prints displayed at the GEM therefore show a lack of technical control, ranging from colour saturation to white balance, that affected his work with both camera and printer. Several prints are dominated by a blue tint, among them the one, In Pursuit of Magic, from which the title of the exhibition was taken. Some colours, especially the greens, shout out of their frames, reminding the visitor of badly processed and over-saturated Fuji Velvia transparencies, and the blue cast on the green of some trees and lawns make them look utterly artificial, as if they were made of plastic. It is true though that in many instances Lyons used colour as an effective added element in his photographs. One clear example is the photograph that I would call Angel/Devil. In spite of the ubiquitous blue cast, the slight orange of the texture of the two wings (more visible once the blue cast has been corrected) and the red of a devil’s horns and tail are crucial to the dynamic quality and meaning of the image. So, whereas colour adds impact and meaning and expands the aesthetic qualities of Lyons’s art to a new sphere in many cases, in others it becomes, at best, a distraction. The inadequate colour treatment in some of the photographs definitely impacts the body of work in terms of consistency and coherence, areas that were among Lyons’s most obvious strengths.

New Can Be the Enemy of Good. What can be said, as a conclusion, about this exhibition and its catalogue?6 First, they are interesting documents, a first-hand look and a guide for visitors who want to discover a major body of work by a great American visionary of the second half of the twentieth century. Novice, student, museum habitué, or photographer – all will benefit from it. The catalogue should not be missed, as it adds to the exhibition an extremely well-documented biographical essay by Jessica McDonald – an excellent choice by the two curators.7 However, both the exhibition and its catalogue suffer from being compromises between a retrospective and the first presentation of a body of work in progress. Both would require more space for such an abundance of photographs. This project illustrates another interesting point: it can be problematic to show new work in progress, especially when the artist has not totally mastered a new technique. Under such conditions, the artist’s absence makes the task almost impossible for those left to carry it to completion. Both exhibition and catalogue had been expected, especially three years after Lyons’s final going out-of-focus. They could have been historical milestones generated under exceptional circumstances: the vision of a renowned artist, a local, national, even international celebrity, at the very end of his career (with all the perspective and wisdom that are associated with this stage) crossed with that of a curator from a totally different generation. Obviously, Lyons’s original goal was different, probably biased by a survival instinct that pushed him to ignore hurdles that he had clearly identified for others at other times, as expressed in 2007. The responsibility for organizing the colour work fell upon a young curator, specialized in conservation and not so much in the aesthetics and philosophy of photography and the complex issues that Lyons questioned all his life. Her respect for the photographer’s choice accounts for the size of a group of colour photographs somewhat inconsistent with the artistic rigour and coherence displayed in the preceding bodies of work in black and white. Another example of this discrepancy, in my view – I had known Lyons for thirty years – is the choice of the title of the show, which did not have the humour and relevance, the décalage, of the other titles. From all the photographs that he took for a period of over fifty years, the pursuit that emerges is not that of magic but that of meaning, of a humanistic and understanding connection with our environment and with our fellow human beings. His photography has been a constant questioning of human values, aspirations, frustrations, and culture, always expressed through his visual language of choice, photography. That is what he should and will be remembered for. There’s nothing magical in that, just an enlightened mind relentlessly at work and expressing itself through a mastered medium of choice.

English version by Bruno Chalifour

2 See Jessica McDonald, Nathan Lyons: Selected Essays, Lectures, and Interviews (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012).

3 The actual quotation is, “The eye and the camera sees more than the mind knows,” as if eye+camera=1.

4 Jack Kerouac in the introduction to The Americans(1959).

5 Nathan Lyons and Carl Chiarenza, with Rick Hock, “Speaking in Black and White,” Images 45, no. 1 (Spring 2007:4–11.

6 Jamie Allen, Lisa Hostetler, and Jessica McDonald, Nathan Lyons: In Pursuit of Magic (Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum, 2019).

7 For more context on Lyons, see McDonald, Nathan Lyons. The University of Texas Press is also the printer of the catalogue In Pursuit of Magic, in which the duotone printing, which adds a yellowish gray to Lyons’s otherwise neutral photographs, is not totally successful; nor is the choice of a bland photograph for the cover, probably selected by the graphic designers who needed a simple background for their text, which does really represent the work shown inside the book.

Bruno Chalifour is a photographer who has been teaching and writing about photography for more than forty years. He moved to the United States in 1994 and was editor-in-chief of the magazine Afterimage, published by the Visual Studies Workshop, in Rochester, New York (2002–05) and director of Spectrum Gallery, in Rochester (2014–15). His essays have been published in France, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and his images have been in numerous solo and group exhibitions in France and the United States.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 112 – COLLECTIONS REVISITED ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Nathan Lyons, An Exploration of Photography as Visual Language — Bruno Chalifour ]