[Fall 2012]

Howard Becker wrote an essay called “Do Photographs Tell the Truth?” in 1986, and the question still seems pertinent. Although today we admit that the photographic image constitutes a (re)construction of the world and not a reproduction of reality, a certain legalistic conception of photographs tends to be maintained.1 Despite formatting, storyboarding, or fictionalization, the photographic surface (like the filmic image), indissociable from how it is mechanically produced, raises the idea that the photograph offers a sort of “truth” of things. Are we, as Jacques Rancière suggests, in an age in which “writing History and writing histories arise from a single regime of truth”2 – in which reality and fiction intertwine within a single space, which we apprehend according to similar knowledge criteria? The photographic practice of New York artist Taryn Simon3 in fact consists of probing, even foiling, the links between reality and its image through both thematic registers and formal strategies. Last fall, the Milwaukee Art Museum presented the exhibition “Taryn Simon: Photographs and Texts,” featuring three recent photographic series: The Innocents (2003), An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (2007), and Contraband (2010). By choosing to accentuate Simon’s arrangements of texts and images, the exhibition curator, Lisa Hostetler, recognized the importance of this mechanism in undermining viewers’ perception and disorienting their interpretation.

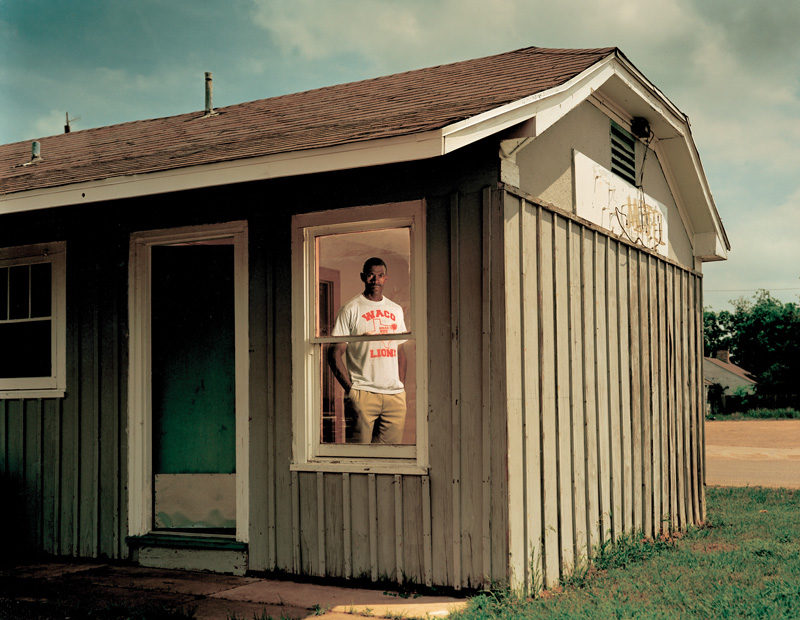

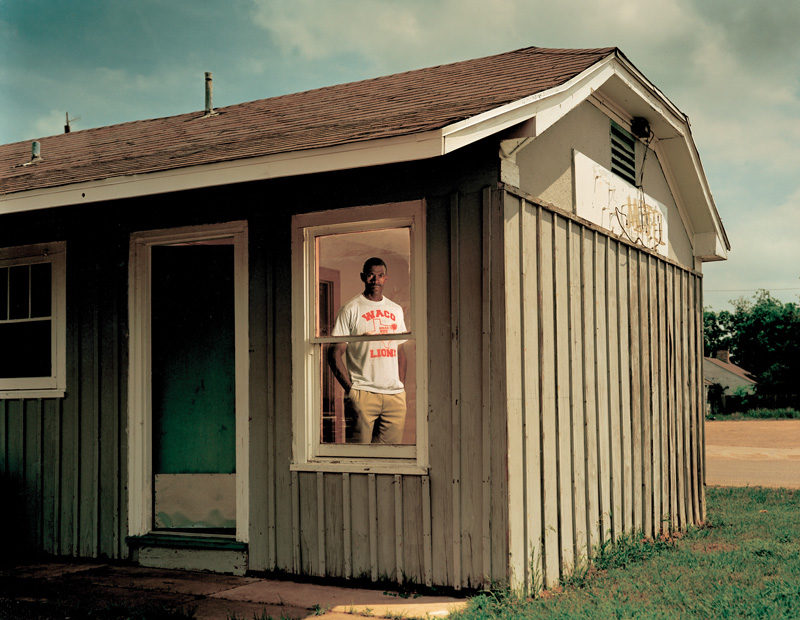

Taryn Simon, CALVIN WASHINGTON, C&E Motel, Room No. 24, Waco, Texas, 2002, de la série / from the series The Innocents, épreuve chromogénique / c-print, 122 x 152 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian gallery. C’est ici qu’un informateur déclarait avoir entendu Washington se confesser. Condamné à la prison à vie pour crime grave, il a subi 13 ans d’emprisonnement.

Taryn Simon, TROY WEBB, Scene of the crime, The pines, Virginia Beach, Virginia, 2002, de la série / from the series The Innocents, épreuve chromogénique / c-print, 122 x 152 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian Gallery Condamné à 47 ans de prison pour kidnapping, viol et cambriolage, il a passé 7 ans derrière les barreaux.

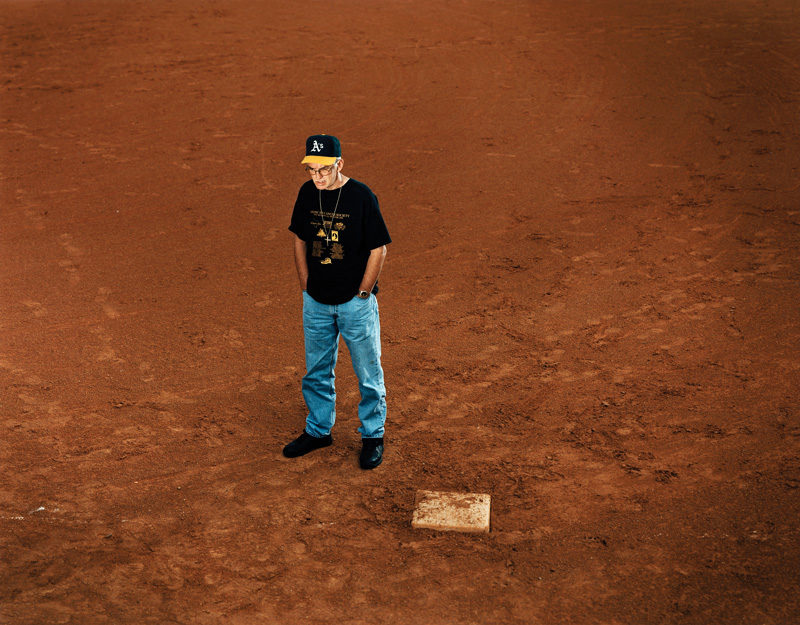

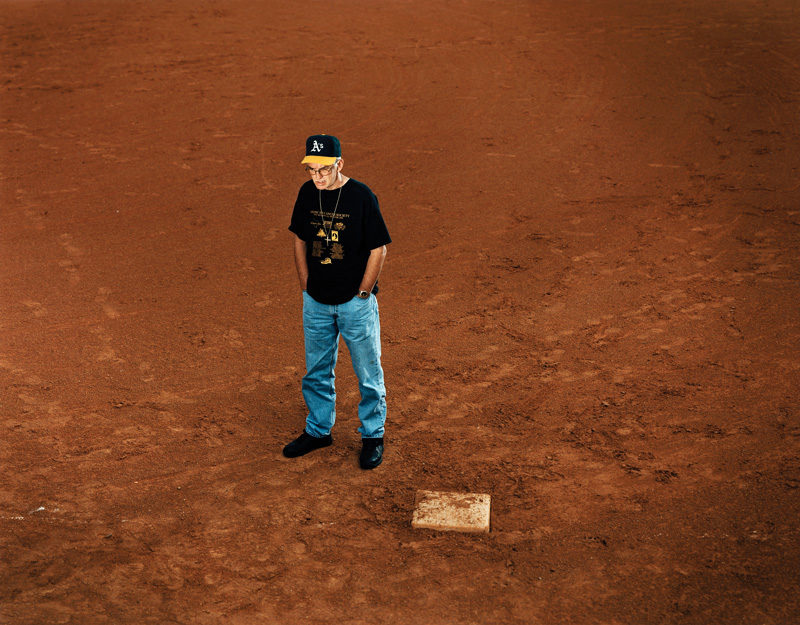

RON WILLIAMSON, Baseball field, Norman, Oklahoma, 2002, de la série / from the series The Innocents, épreuve

chromogénique / c-print, 122 x 152 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

Williamson had been drafted by the Oakland Athletics before being sentenced to death. Served 11 years of a death sentence for First Degree Murder.

Williamson a été recruté par l’équipe des Oakland Athletics avant d’être condamné à mort. Peine capitale pour meurtre au premier degré ; 11 ans en prison.

Dynamo III, Studying Magnetic Fields and Impending Pole Reversal, University of Maryland, Nonlinear Dynamics Laboratory, College Park, Maryland, 2007, de la série / from the series An American Index of

the Hidden and Unfamiliar, épreuve chromogénique / c-print, 95 x 1113 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

Ceci est la plus importante maquette du noyau terrestre, constituée d’une sphère métallique de 10 pieds de diamètre. Elle contient 14 tonnes de sodium liquide extrêmement inflammable, représentant le noyau externe en fusion, et une boule de cuivre de 3 pieds de diamètre qui représente le noyau interne (solide) de la Terre. Construite par des géophysiciens dirigés par le Dr Daniel P. Lanthrop, elle génère sa propre dynamo, un champ magnétique autoexcité et autoalimenté. Comme le Soleil

et Jupiter, la Terre est entourée d’un champ magnétique qui s’étend à des milliers de kilomètres dans l’espace. Cette magnétosphère protège la Terre et son atmosphère des rayonnements ultraviolets et de particules mortelles très chargées. Le champ magnétique de la Terre oriente l’aiguille de la boussole vers le nord et guide les animaux dans leurs routes migratoires, favorisant ainsi la reproduction et la survie des espèces.

Taryn Simon, Death Row Outdoor Recreational Facility, “The Cage”, Mansfield Correctional Institution, Mansfield, Ohio, 2003-2007, de la série / from the series An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, épreuve chromogénique / c-print, 95 x 1113 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

Institution, les détenus du couloir de la mort ont droit à une heure par jour de détente à l’extérieur, dans des zones de réclusion individuelles ou collectives surnommées cages ou enclos. Les cages séparées comprennent uniquement une barre d’exercice et il est interdit d’y apporter quoi que ce soit. Les cages non séparées contiennent un panier de basketball, et

les détenus peuvent apporter certains articles dont un ballon de basket, une radio, un paquet de cartes et

des cigarettes. Tous les détenus du couloir de la mort à Mansfield sont décrits comme ayant des « problèmes de santé mentale ». Dans le cas Atkins v. Virginia, la Cour suprême des États-Unis a déclaré que l’exécution des personnes ayant un déficit mental était anticonsti- tutionnelle. La définition de la déficience mentale est

une question controversée, abordée notamment dans le projet de réforme de la loi sur la peine de mort (Death Penalty Reform Act) de 2006.

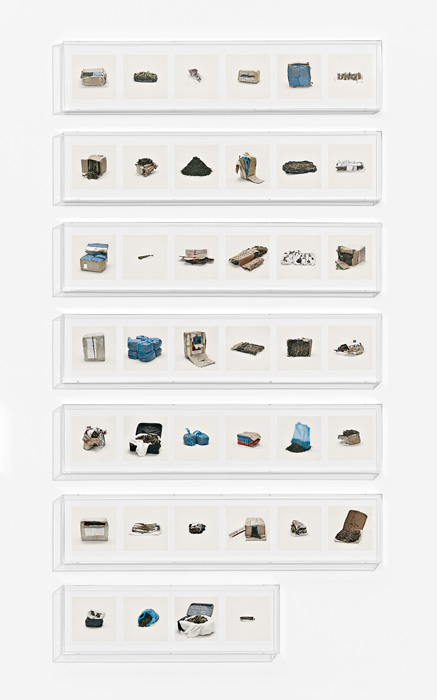

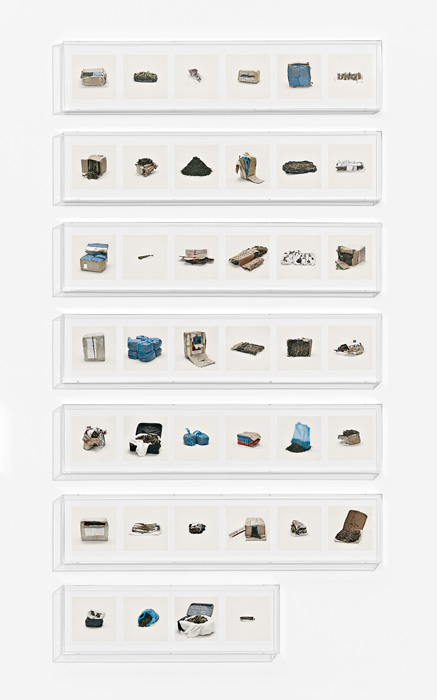

Taryn Simon, KHAT (IILLEGAL), 2010

de la série / from the series Contraband,

épreuves chromogéniques / c-prints. © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy

of Gagosian Gallery

Taryn Simon, GBL, COMPONENT OF DATE RAPE DRUG (IILLEGAL) (détails / details), 2010

de la série / from the series Contraband,

épreuves chromogéniques / c-prints. © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy

of Gagosian Gallery

Taryn Simon, GUINEA PIGS (PROHIBITED), 2010

de la série / from the series Contraband,

épreuves chromogéniques / c-prints,

© Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy

of Gagosian Gallery

Taryn Simon, White Tiger (Kenny), Selective

Inbreeding, Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge

and Foundation, Eureka Springs, Arkansas, 2007,

de la série / from the series An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, épreuve chromogénique /

c-print, 95 x 113 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

In the United States, all living white tigers are the result of selective inbreeding to artificially create the genetic conditions that lead to white fur, ice-blue eyes and a pink nose. Kenny was born to a breeder in Bentonville, Arkansas on February 3, 1999. As a result of inbreeding, Kenny is mentally retarded and has significant physical limitations. Due to his deep-set nose, he has difficulty breathing and closing his jaw, his teeth are severely

malformed and he limps from abnormal bone structure in his forearms. The three other tigers in Kenny’s litter are not considered to be quality white tigers as they are yellow-coated, cross-eyed, and knock-kneed.

Aux États-Unis, tous les tigres blancs vivants sont issus de croisements consanguins destinés à obtenir artificiel le ment leurs caractéristiques génétiques : fourrure blanche, yeux bleu clair, museau rose. Kenny est né chez un reproducteur de Betonville, en Arkansas, le 3 février 1999. À cause de la consanguinité, Kenny souffre de handicaps mentaux et physiques. Son museau enfoncé l’empêche de respirer normalement et de refermer la mâchoire ; il a les dents très déformées, et il boite à cause d’une malformation dans les os des pattes antérieures. Les trois autres tigres de la portée ne sont pas considérés comme des tigres blancs de bonne qualité, car ils ont la fourrure jaune, les genoux cagneux, et ils louchent.

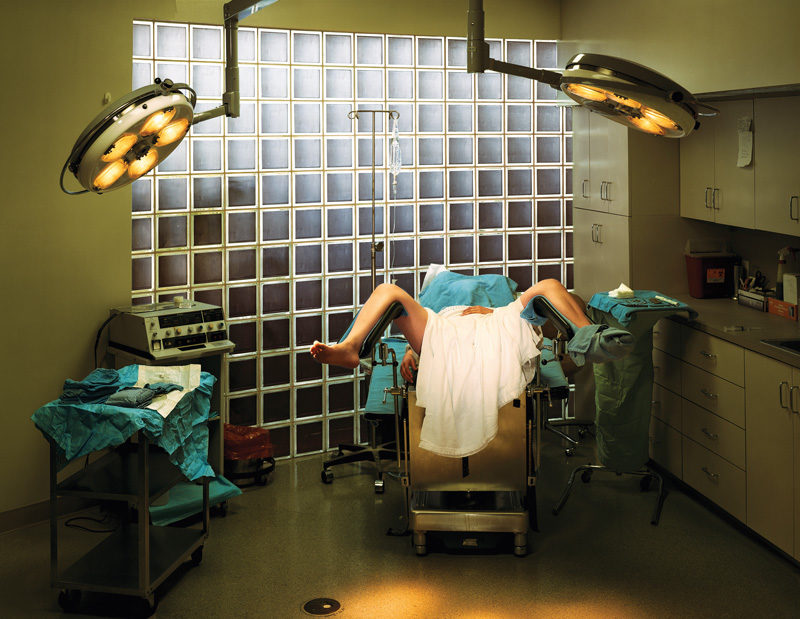

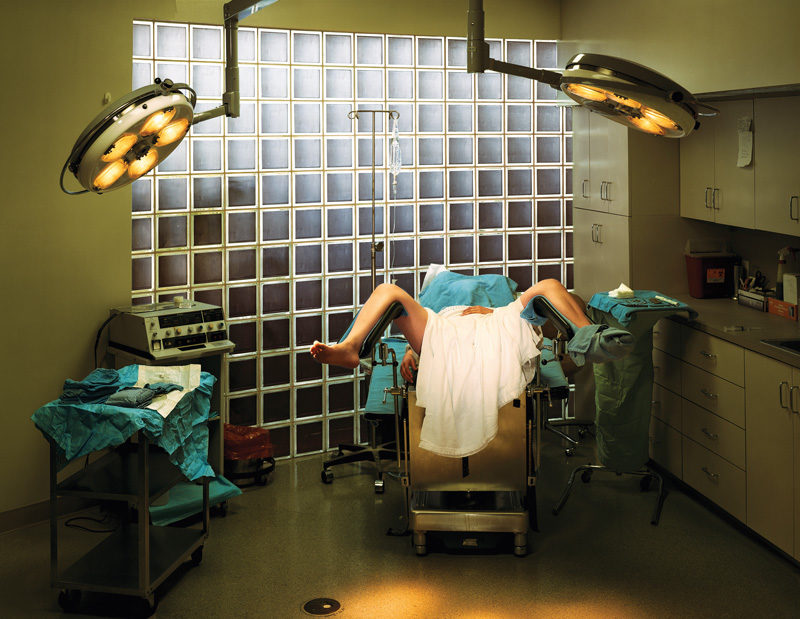

Taryn Simon, Hymenoplasty, Cosmetic Surgery, P.A., Fort Lauderdale, Florida, 2007, de la série / from the series An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, épreuve chromogénique / c-print,

95 x 113 cm, © Taryn Simon, permission de / courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

The patient in this photograph is 21 years old. She is of Palestinian descent and living in the United States. In order to adhere to cultural and familial expectations

regarding her virginity and marriage, she underwent hymenoplasty. Without it she feared she would be rejected by her future husband and bring shame upon her family.

She flew in secret to Florida where the operation was performed by Dr. Bernard Stern, a plastic surgeon she

located on the internet. The purpose of hymenoplasty is to reconstruct a ruptured hymen, the membrane

which partially covers the opening of the vagina. It is an outpatient procedure which takes approximately 30 minutes and can be done under local or intravenous

anesthesia. Dr. Stern charges $3,500 for hymenoplasty. He also performs labiaplasty and vaginal rejuvenation.

Cette patiente est âgée de 21 ans. Elle est d’origine

palestinienne et vit aux États-Unis. Pour se conformer aux exigences culturelles et familiales sur la virginité avant le mariage, elle a subi une hyménoplastie, craignant

d’être rejetée par son futur mari et de faire honte à sa famille. En secret, elle a pris un vol pour la Floride, où l’opération fut réalisée par le Dr Bernard Stern, un chirurgien plasticien qu’elle a choisi par Internet. Le but de l’hyménoplastie est de reconstruire l’hymen,

membrane qui recouvre partiellement l’ouverture du vagin chez la vierge. L’opération dure environ 30 minutes et peut être pratiquée sous anesthésie locale ou intraveineuse. La patiente peut quitter la clinique en fin de journée. Le Dr Stern demande 3500 $ pour une hyménoplastie. Il pratique également la labiaplastie

et le rajeunissement vaginal.

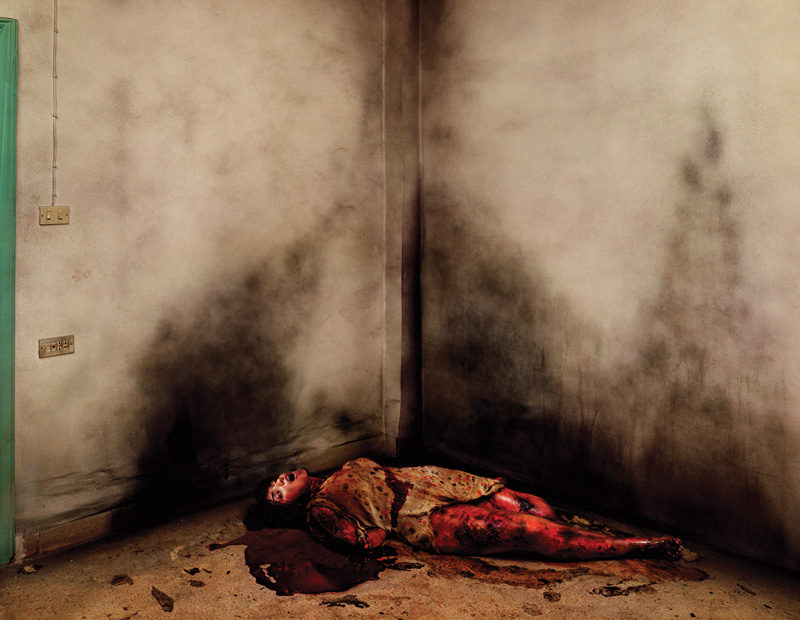

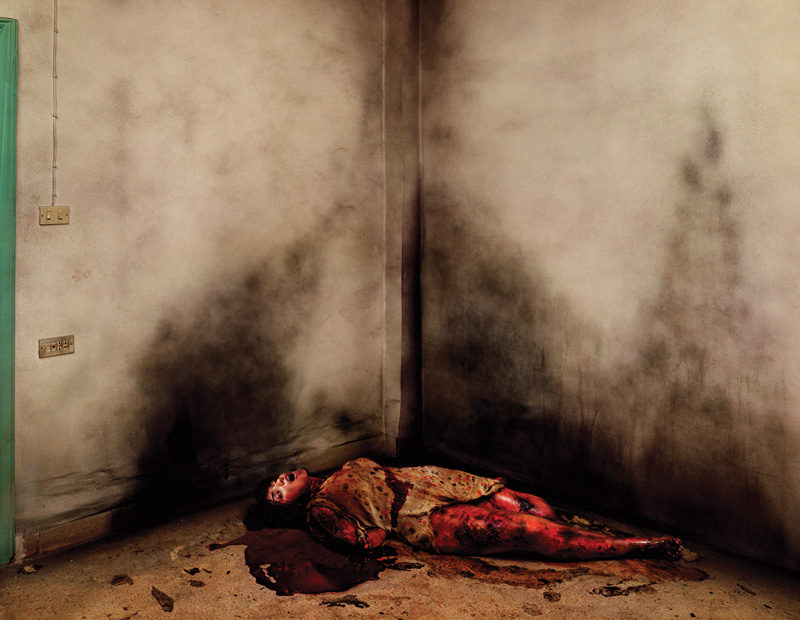

Taryn Simon, Zahra/Farah, 2007-2011, impression jet d’encre / archival inkjet print, 60 x 78 po, (152 x 197 cm). © Taryn Simon, permission de /courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

Iraqi actress Zahra Zubaidi playing the role of Farah

in Brian DePalma’s film Redacted. Simon created this photograph to serve as the final frame in DePalma’s film. Since appearing in the film, Zahra has received death

threats from family members and criticism from friends and neighbors who consider her participation in the film to be pornography. The film is based on the gang rape and murder of a 14 year-old Iraqi girl, Abeer Qasim Hamza, by U.S. soldiers outside Mahmudiya on March 12,

2006. Abeer’s mother, father, and 6-year-old sister were murdered while she was being raped. After the soldiers

took turns raping Abeer, she was shot in the head and her body was set on fire. Four American soldiers of the 502nd

Infantry Regiment were convicted of crimes including rape, intent to commit rape, and murder. In 2011, while this work was on view at the Venice Biennale, Zahra Zubaidi

was granted political asylum in the United States. Her legal defense cited the international exhibition of this

photograph as a contributing factor to her endangerment.

L’actrice irakienne Zahra Zubaidi a joué le rôle de Farah dans le film de Brian DePalma Redacted. Cette pho to graphie a été créée par Taryn Simon pour servir d’image finale

au film de DePalma. Depuis son apparition dans le film, Zahra a reçu des menaces de mort de la part de membres de sa famille, et des critiques de ses amis et voisins, qui considèrent que sa participation au film est pornogra phique. Le film s’inspire du viol collectif et du meurtre d’une

Irakienne de 14 ans, Abeer Qasim Hamza, par des soldats américains, aux abords de Mahmudiya, le 12 mars 2006. Le père, la mère et la petite soeur de six ans d’Abeer furent tués pendant qu’elle était violée. Après que les soldats eurent violé la jeune fille chacun leur tour, ils lui tirèrent une balle dans la tête et mirent le feu à sa dépouille. Quatre soldats américains du 502e régiment d’infanterie

furent condamnés pour des crimes comprenant le viol, l’intention de commettre un viol, et le meurtre. En 2011, alors que cette oeuvre était exposée à la Biennale de

Venise, Zahra Zubaidi a obtenu l’asile politique aux États-Unis. Son avocat mentionnait notamment la présence

de cette photographie sur la scène internationale comme un facteur de risque supplémentaire pour sa sécurité.

Twelve of the fifty portraits in the series The Innocents occupied one of the interconnecting rooms in the gallery. Following a commission executed for the New York Times in 2000 on the release of falsely imprisoned persons, Simon focused on the role played by the photographer in criminal investigations. She then travelled through the United States meeting men and women whose incarceration had been based on erroneous identification attributed to a photograph or an eyewitness. Convicted of robbery, kidnapping, murder, or rape, these individuals were all falsely imprisoned, some for eighteen years, before being exonerated by dna testing.4 At first glance, the large format of the prints (117 x 150 cm) and the obviously elaborate composition attract us. Only when we read the labels accompanying each photograph, which tersely reveal the identity of the individual, the location, and the sentence served, are we plunged into a new, tragic world, in which we feel the empty desolation in the eyes of the subjects. They are in the places that sealed their fate: the scene of the crime, the alibi, the arrest, or the identification. In Simon’s view, this mise en scène reinforces the ambiguity of the relationships between reality and fiction.5

Aside from the photographs, the project includes a publication, which, in this case, Hostetler’s exhibition design follows. The book presents the photographs with texts that, on the one hand, explain the nature of the crime and the context of the arrest, and, on the other hand, quote the person’s testimony. These writings further affect the reception of the images, since they accentuate the reality effect of the photographic construction. Thus, the artist is able not only to show the faults in the American legal system but to transmit the resulting injustice. In this sense, it would have been enriching to directly consult the book, which was displayed, in a very debatable manner, in a covered display case.

Hung in the second room were eighteen photographs from the series An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, made over a four-year period. Like an archaeologist, Simon excavated the American social space searching for sites, spaces, objects, and practices not commonly accessible or simply not well known to the general public. Although these images seem, at first glance, discordant due to the figurative diversity, the accompanying texts, with unusually small typography, force us to reduce our field of vision to the point that we no longer see the image, stating an implacable logic. The explanatory labels reactivate the identity of these “places,” which would otherwise remain anonymous, though interesting from an aesthetic point of view. For example, the image of a body deteriorating in the middle of a wooded area enveloped in dawn light seems tragic, until we read that it is located in a medical and legal anthropological research site at the University of Tennessee. Mixed with the theatrical effect of the image is a reality effect through which we discover something unprecedented. As we make these discoveries, the American imagination is recomposed on the grid of degrees of disenchantment.

Inspired by her first visit to the warehouse for objects confiscated at American customs at John F Kennedy Airport in New York to take pictures for the series An American Index, Simon undertook the project Contraband. With her team, the artist camped out on the site 16–20 November 2009 intending to inventory items that had been banned from entry to the United States because they were deemed illegal or dangerous. Xanax, alcohol, animal cadavers, firearms, exotic fruits, and deer tongues were among the categories within which the 1,075 shots in the series were placed. The images are arranged in translucent cases in a categorized structure. The central placement of the items, photographed against a neutral background, in the images and the careful – almost advertising-like – presentation emphasize both their strangeness and their banality. At the end of each grouping is a brief description of the nature of the product, its provenance, and the reason for its proscription. More than a simple list of objects, this collection reveals the importance of transborder flows in the era of what Marc Augé calls supermodernity and shows, at the same time, what the United States is afraid to allow onto its territory.

By the end of our visit, we have certainly been impressed with the beauty of the images that Simon has produced, but even more with the revelations resulting from the complex relationship between the photographs with a calculated aesthetic and the texts with a plain, impersonal style. In fact, the formal layout becomes subversive as it deconstructs what we believe we are seeing and constructs what we should see. The contextualization that Simon proposes through written intervention attests to the insufficiency of the photographic image to “express” the world and reveals its fictive potential. Paradoxically, the written material amplifies the reality effect of the fictionalized image by conferring upon it a thickness, without, however, defining the imaginary. In this case, the question that arises is perhaps no longer whether the photograph tells the truth, but how we build our knowledge of the world through the image. How do we build photographic truth?

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Régis Durand and Paul Ardenne, Images-mondes : de l’événement au documentaire (Paris: Monografik éditions), p. 11.

2 Jacques Rancière, Le partage du sensible (Paris: La Fabrique éditions), p. 61 (our translation).

3 The artist’s Web site is http://tarynsimon.com/

4 As Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck write in the introduction to The Innocents, the process leading to dna testing on individuals already found guilty is difficult – even impossible in some states. Significantly, today identifications must correspond to the results of dna tests.

5 Taryn Simon, The Innocents (New York: Umbrage Editions, 2003), pp. 6–7.

Mirna Boyadjian is currently studying for a master’s degree in art history at the Université du Québec à Montréal; her subject is the work of New York artist Taryn Simon. She also works at the Observatoire de l’imaginaire contemporain (OIC).

This text is reproduced with the author’s permission. © Mirna Boyadjian

Purchase this article