[Spring-Summer 2018]

By Pierre Dessureault

At Expo 67, a huge celebration of human progress and great festival of the image in all of its technological and expressive possibilities, the Christian Pavilion designed by Charles Gagnon offered a counterpoint to the event’s sea of triumphant optimism. This small pavilion, conceived by its designer as a multimedia photography and film installation, portrayed a tortured world living in the fear – very real at the time – that an atomic mushroom cloud would annihilate the planet.

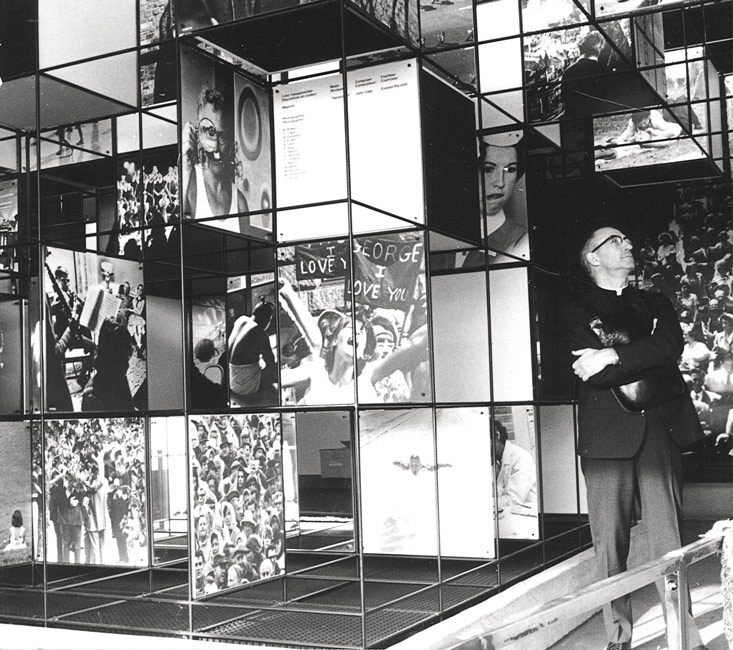

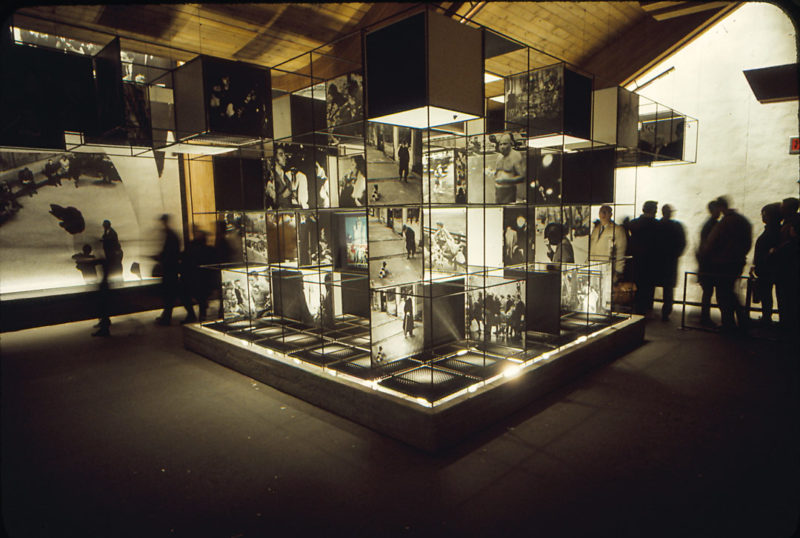

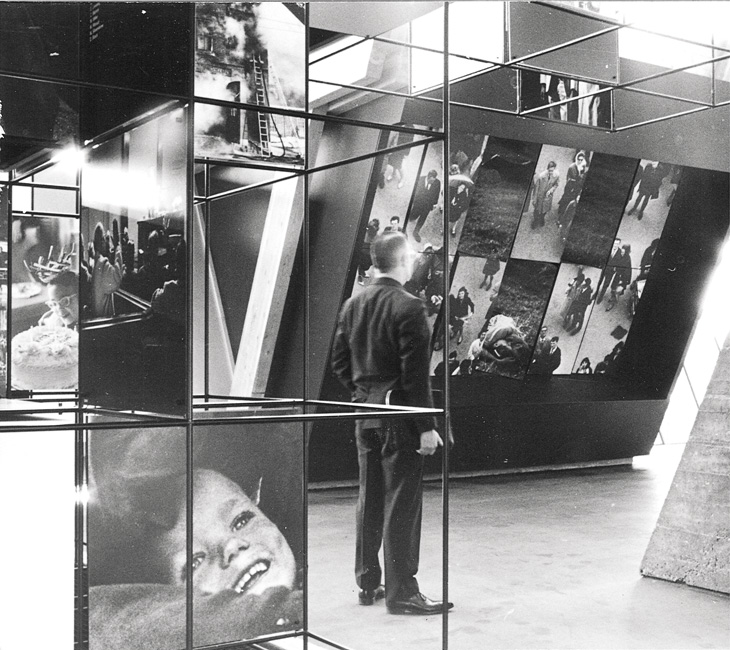

The pavilion,1 produced through the collaboration of eight Christian churches, stepped away from conventional representations of religions to offer an immersive journey divided into three zones that defined different stages in the visitor’s path. The first was a space filled with more than three hundred photographs reflecting “all aspects of daily life, good or bad, interesting or banal.”2 They were spread out in a vast dark space, arranged on cubic metallic shapes and covering the walls to offer a decentred vision of the state of the world.

The photographs displayed were high-quality documents making use of the descriptive capacities of the medium to present situations in which truth wins out over artifice. “Most of the photographs exhibited in the pavilion,” Gagnon tells us, “were obtained from the Magnum and Black Star photo agencies in the United States and included images by well-known photographers such as Cornell Capa, Robert Capa, Helen Levitt, and Bruce Davidson.”3 Added to this list of photographers, notably, were David Seymour, Robert Frank, and Canadian John Max. The pictures in this zone brought focus to the humanist gaze and belonged to a time when the belief in the power of images was still intact – when the truth of the representation and the credibility and authenticity of the photographic document were incontestable.

The open structure created by Gagnon invited spectators to see the photographs from the different points of view in the environment as they made their own way along the path defined by the exhibition layout. Free to move in front of and around the images, free to contemplate and enter dialogue, both physical and intellectual, with them, visitors wove connections among them that changed as their gaze wandered, transposing them into a space that became subjective depending on their own experience of the world.

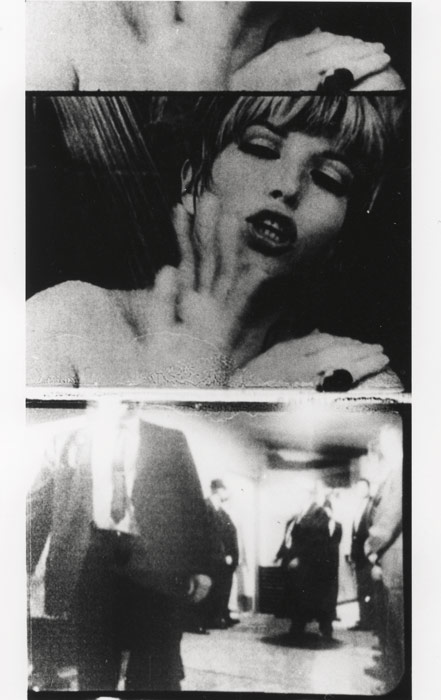

“A staircase now leads to the crypt level at the end of a twisting corridor full of nightmare images.”[4] An immense surrealist-inspired collage showing the depersonalizing effect of consumer society and a few large-size images displaying desolation and misery marked the break with what has preceded and presaged the subject of the film that comprised the second zone.

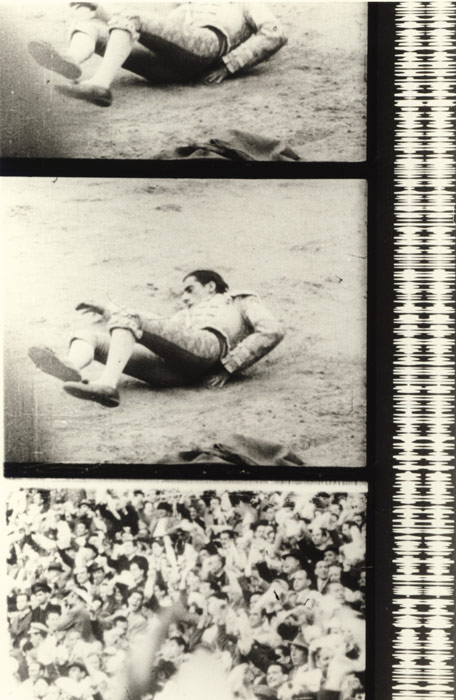

The Eighth Day[5] not only surveyed the violent events that had roiled the twentieth century almost uninterrupted, but also showed that the world featured in the first zone was their result, as the first sequences of the film, showing urban agitation, demonstrated. The following sequences gave a chronological account of the convulsions that had shaken the course of the century. The archival documents used by Gagnon referred to instantly recognizable events that could be situated in time and space. Subjects such as the funeral of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Great War, the heads of state gathered to sign the Armistice, the Spanish Civil War, Mussolini, the conflict in Ethiopia, Hitler and the Second World War, Nazi concentration camps, the bombing of Hiroshima, the assassinations of Kennedy and Oswald, and Buddhist monks immolating themselves in Vietnam gave rise to images that had become emblematic and were crystallized in the collective historical conscience as essential moments in the global march of time.

Rupturing the viewers’ usual perception of these images through clashing juxtapositions, Gagnon summoned the past in the present of the film, endowing the news clips, and the events that they portrayed, with a unique configuration. In doing this, he returned to them their power of emotive persuasion and revealed their potentialities, exposing their continuity and visually reconstructing their meaning – and not their denotation. For there was no truth intrinsic to the documents, only the traces of events with which they were imprinted – traces struggling to sketch the contours of a history that would otherwise remain impenetrable.

A historical distance from both events and images remained, however. The first part of the film, which went up to the Second World War, aligned sequences, passing from one event to another and foregrounding the descriptive power of images that looked back at the course of an already old history. This distance is inherent to a document filmed from a point of view that adopts every appearance of neutrality.

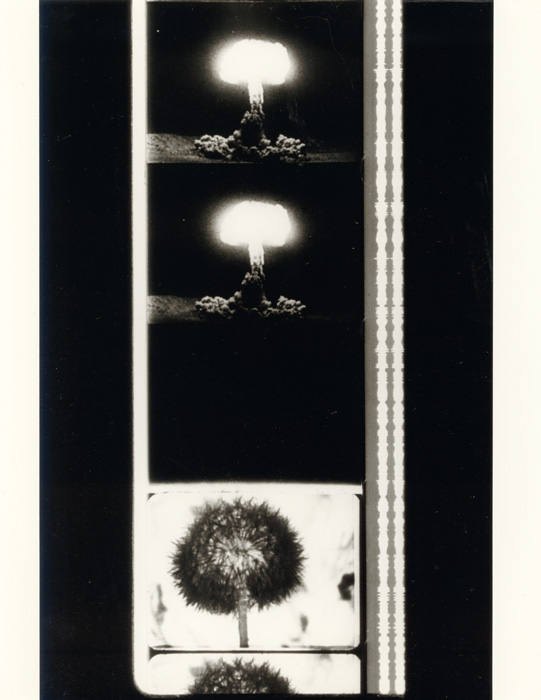

The second part of the film, which led from the Second World War to the inexorable end, gradually erased the temporal gap. The fractures in history caused by the revealing of the Nazi extermination camps and the bombing of Hiroshima – the destructive power of which was just barely beginning to be imagined – belonged to a recent past for many visitors. The short sequence of the self-immolating Buddhist monk dying live on camera plunged spectators into the immediate present of the Vietnam War. No distance could soften the impact of this document, which delivered unfiltered reality. From this point, viewers were immersed in an uninterrupted flow of images, edited in parallel, of displays of consumer goods, ads objectifying women, and mountains of garbage and car carcasses, plunging them into the current time of developing consumerism. This frantic cascade of still images, many of which were taken by John Max at Gagnon’s request, offered a view of trash as the ultimate end of a society imprisoned in its frenzy of consumption and led inexorably to the final visual metaphor: a still close-up on a dandelion flower; an atomic explosion; return to the dandelion, this time in negative, as it closed. Things and their inverse. Black.

The third zone concluded the visit on a note of relative optimism. “The visitor finally leaves the crypt to enter a spacious gallery that displays large photographs and several biblical texts. Life may not be irremediably stripped of meaning and hope is not a meaningless word because ‘light still shines in the darkness and the darkness can never extinguish it.’”[6]

Fifty years later, for the exhibition À la recherche d’Expo 67, presented at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal from June 21 to October 9, 2017, Emmanuelle Léonard took up where Gagnon, aware that his subject had not been exhausted, had left off. “When working on the film,” Gagnon noted, “I came to realize that the strongest thing about violence and the most abstract thing about violence is it’s sequential nature, that war has never stopped, and that it is just the leading of one conflict into another conflict. I could keep this film going on forever; there is a lot of material, now; like My Lai, the Hoffman trial. It’s like adding to a research file.”[7]

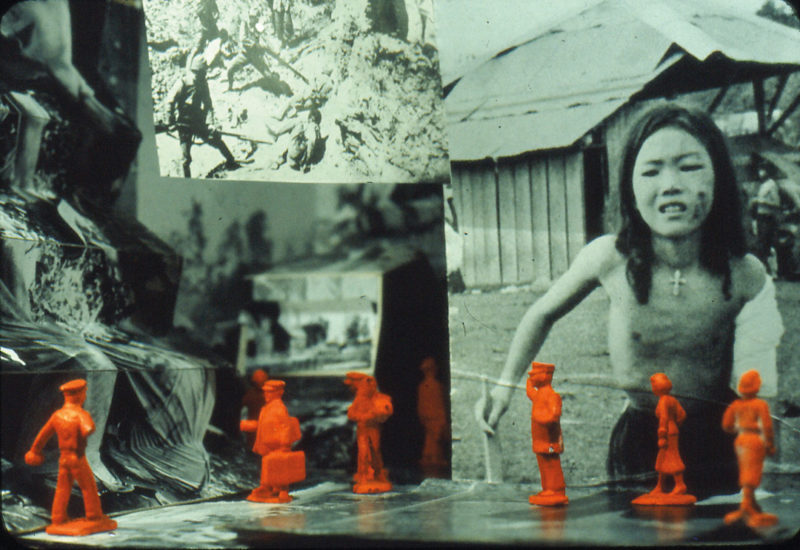

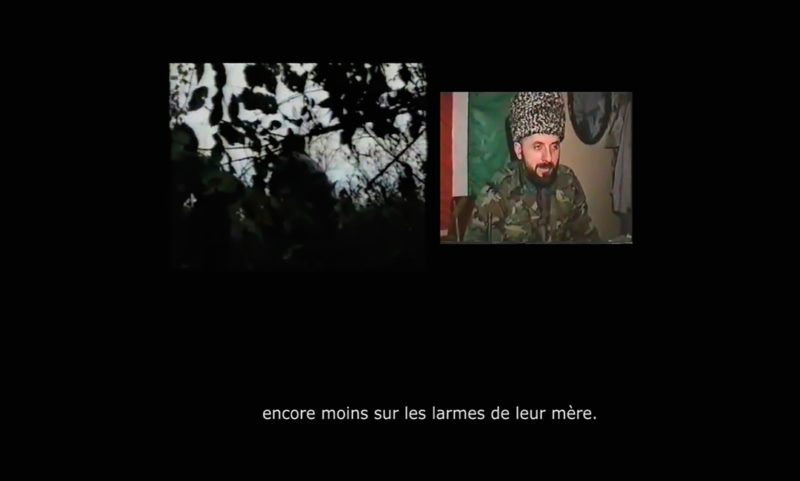

Le huitième jour 1967-2017 is not a reprise of Gagnon’s film to update it to current tastes, but a sequel. Léonard describes it as “a two-projection video installation made from archives covering conflicts from 1967 to the present. The documents come from different sources on the Internet: television, state, and military archives, self-promotions by guerrillas or recordings of their actions, propaganda from various camps.”[8]

From the start, we observe that both the source and the status of images have changed radically over time. Unlike Gagnon’s choice of news filmed with denotation and specificity, firmly planted in the expressive and representational register, produced by information professionals, and destined for a social use, the images that Léonard uses are drawn from the great, undifferentiated melting pot of the Internet, which peddles a multitude of anonymous images with no purpose but to display the duration of the moment that they portray. In contrast to the information presented in Gagnon’s film, which formed a montage leading inexorably to atomic horror, the banality and muted violence of the video excerpts selected by Léonard are striking. The videos of nocturnal bombardments of Iraq in 2008 echo those of the First Gulf War, which served to legitimize the United States’ intervention by reducing Operation Desert Storm to a few streaks of light in the night sky over Baghdad. Due to their lack of representational content, these images came to signify a surgical war and reduced the conflict to a technological confrontation from which all human presence was erased. As an example, the opening sequence of the video shows a night-vision view of a drone attack on a military target as the soundtrack transmits the comments of the operators, who are obviously treating the operation as an exciting video game. The banality of the document. The trivialization of violence. Dehumanization. Derealization.

This is one of the notable features of the status of images disseminated in vast streams on the Internet: there is no longer the mediation and transposition of reality designed to provide the viewer’s gaze and, especially, judgment with a vision of the configuration of the world. Instead, they form a separate reality, the only coordinates of which are within the universe of images. By selecting certain documents from this great indistinct mass, Léonard adopts a point of view from which she paints a portrait of wars at the level of the daily life of the combatants: “Excerpts of walking, running, camps, waiting, avoiding cadavers”[9] constitute its framework. The editing brings out a stance in favour of realism and distance that, without being that of the war reporter devoted to capturing head-on the ins and outs of the conflict that it is his or her mission to cover, serves as a guideline for setting sequences in a web of contrasts, affiliations, and echoes. Unlike Gagnon’s montage, which exacerbated the expressive qualities of images in order to provoke spectators’ reflections on their own position in the world, Léonard’s aligns, in a fluid continuity, dedramatized documents that sometimes are deployed across the entire surface of both screens, and sometimes respond to each other from screen to screen. The picture of conflicts that emerges from these sequences is one of repetition ad infinitum of similar gestures, similar situations, without regard to the positions of the protagonists.

The texture of the visual materials chosen by Léonard, their declared materiality, returns substance to dematerialized images and provides clues to their origins and pathways. “The mode of information is part of the information and enriches it.

It was one of the principles in the selection of documents: each time it was possible . . . to bring the document closer to the concrete circumstances of its making, making it so that the information does not appear as a cosa mentale, but as a material with its grain, its rough spots, and sometimes its splinters.”[10] These marks constitute traces of both the life of images and the successive reprises of those images in a multitude of changing contexts.

“The world is what it is, which is to say, nothing much,” wrote Camus the day after the bombing of Hiroshima.[11] What if, today, the world of images were no more than a gigantic magma taking the place of reality, and what if the nuclear apocalypse ending Gagnon’s film consisted, fifty years later, of a massive computer virus attack that paralyzed everything down to our most ordinary activities? It is reminiscent of the linearity of the Gutenberg galaxy, which McLuhan prophesied would end, leading to a radically new way of thinking of the world as a multidimensional whole that the invention of new forms of instant communication and the extension of new media would transform into a global village . . . “The world is what it is.”

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Rapport général sur l’exposition universelle de 1967, vol. 1 (Ottawa: Imprimeur de la Reine pour le Canada, 1969), 492. General Report on the 1967 World Exhibition, vol. 1 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1969)

3 Gagnon, “Christian Pavilion,” 148–49.

4 Expo 67. Album mémorial de l’Exposition universelle et internationale (Thomas Nelson & Sons (Canada), 1968), 284.

5 Le huitième jour, Charles Gagnon 4 Films, DVD and catalogue, Spectra Media, 2009.

6 Expo 67, 286.

7 Charles Gagnon, “The Eighth Day,” quoted in Philip Fry, “Foundations: Notes on Charles Gagnon’s Work,” in Charles Gagnon (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1978), 89, 91.

8 Emmanuelle Léonard, Énoncé d’intention en introduction de sa bande vidéo, MACM, 2017 (our translation).

9 Ibid. (our translation).

10 Chris Marker, “Repères,” in the booklet presenting the DVD Le fond de l’air est rouge (Arte France, 2008), 10 (our translation).

11 Albert Camus, “Éditorial, Combat, 8 août 1945,” in Essais (Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1965), 291; translation in Albert Camus: Between Hell and Reason, trans. Alexandre de Gramont (Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press, 1991), 110.

Pierre Dessureault is an expert in Canadian and Quebec photography. As a curator, he has organized some fifty exhibitions, published catalogues, contributed to books, and written a number of articles on photography. Since his retirement, he has devoted himself to studying international photography in a historical perspective and, reviving his early interest in philosophy and aesthetics, to exploring in greater depth the theoretical approaches that have marked the history of the medium.

Charles Gagnon, painter, photographer, and filmmaker, was an outstanding figure in Quebec and Canadian art. He is known for his body of work in abstract painting and for his photography practice, which he maintained throughout his life. These two interests were combined in his later works. Among his many distinctions were the Prix Paul-Émile-Borduas, in 1995, and the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts, in 2002. Gagnon taught at the University of Ottawa for twenty years. He was born in Montreal in 1934 and died there in 2003. charlesgagnonartist.com

Emmanuelle Léonard uses photography, video, and film. Her work has been in numerous solo and group exhibitions, in Canada and abroad. In 2005, she received the Prix Pierre-Ayot. She has a BFA from Concordia University and a master’s degree in visual and media arts from the Université du Québec à Montréal. She lives and works in Montreal. emmanuelleleonard.org

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 109 – REVISITER ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Charles Gagnon | Emmanuelle Léonard, Le huitième jour – Pierre Dessureault, Expo 67: The Christian Pavilion and Le huitième jour ]